Advertorial

01 October 2023

Update on the use of inhalers in feline asthma

Inhaled therapy is key to the successful management of feline asthma. A recent study looked at how spacer design may impact clinical outcomes.

Feline asthma is a common cause of feline lower airway disease and is estimated to affect between one and five percent of the cat population1. All types of cat may be affected, but some such as the Siamese may be predisposed.

The condition is caused by a Type 1 hypersensitivity response to inhaled allergens2, resulting in eosinophilic airway inflammation, bronchoconstriction and mucus production. In the long term this can lead to irreversible airway remodelling and lifelong management is needed to control clinical signs and prevent this outcome.

What are the clinical signs of feline asthma?

A cough is the most common presenting sign of feline asthma. It may be accompanied by an expiratory respiratory pattern, typified by a prolonged expiratory phase and increased abdominal effort. Wheezing, audible on auscultation may also be present. Cats will often adopt a characteristic posture, crouching low to the ground with head and neck extended to straighten the airway.

However, not all cats with asthma will present with a cough, and indeed the absence of a cough does not rule out the condition. Patients may present in acute respiratory distress, and in some cases, this may be the only presenting sign.

Creating a comprehensive management plan

The aim of a feline asthma management plan is to reduce exposure to inhaled allergens, treat episodes of acute respiratory distress and control ongoing clinical signs. With potential triggers including pollen, dust and mould, allergen control can be challenging, and most patients will need some form of medical management in addition.

The main pharmaceutical agents used are glucocorticoids, to reduce bronchial inflammation, and bronchodilators, to reduce bronchospasm and open up the airways.

Medication may be administered by injection, orally or by inhalation. Injectable medication is normally reserved for emergencies and acute respiratory distress, when supplementary oxygen alongside sedation to reduce anxiety may be required too. After initial stabilisation, most patients will be transitioned onto oral medication.

Systemic treatment: a short-term solution

While systemic therapy is commonly used, especially in the management of acute respiratory distress, glucocorticoids are poorly tolerated in the long term, with increased risk of conditions such as pancreatitis and diabetes in feline patients.

A recent study in dogs compared the use of inhaled fluticasone with oral prednisone in 30 dogs with tracheal collapse3. As well as improved clinical outcomes, the fluticasone treated dogs showed a lower incidence of signs of hypercortisolism compared to the prednisone group.

Furthermore, glucocorticoid use is contraindicated with some diseases, including diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure and chronic kidney disease1. It is for this reason, that inhaled medication is advocated for the long-term management of many respiratory diseases, and a transition to inhaled medication after the initial stabilisation period is recommended. This transition process should be gradual, over the course of around two weeks.

Advantages of inhaled medication

Administering medication by inhalation enables the targeted delivery of pharmaceutical agents to the lungs and lower airways, with far fewer of the endocrine or immune side effects associated with systemic medication, and this has revolutionised the management of feline asthma. By directly targeting the site of disease pathology, inhaled therapy also requires a substantially lower dose to achieve the same therapeutic effect when compared to systemic administration.

In human asthma, metered dose inhalers (MDIs) provide optimal medication delivery through slow, deep breaths, coordinated with device actuation. However, in veterinary patients, including cats, achieving this ideal inhalation technique is challenging, if not impossible. To overcome this hurdle, and enable effective medication delivery, MDIs are combined with a spacer fitted to a face mask. The spacer provides a hollow tube or chamber with a one-way valve, into which the medication is delivered. It then holds the medication suspended until the cat is ready to take a breath.

The impact of spacer design on respiratory drug delivery

Spacers should have a fitted, non-stick mask designed specifically for cats and the correct valve. Chamber volume and length can also impact pulmonary deposition of medication. With a variety of designs and a ready availability of spacer devices online, a study presented at the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) Forum 20204, examined the impact of various spacer designs, including the AeroKat® Chamber (Figure 1), on respiratory drug delivery, as well as potential implications for medication costs.

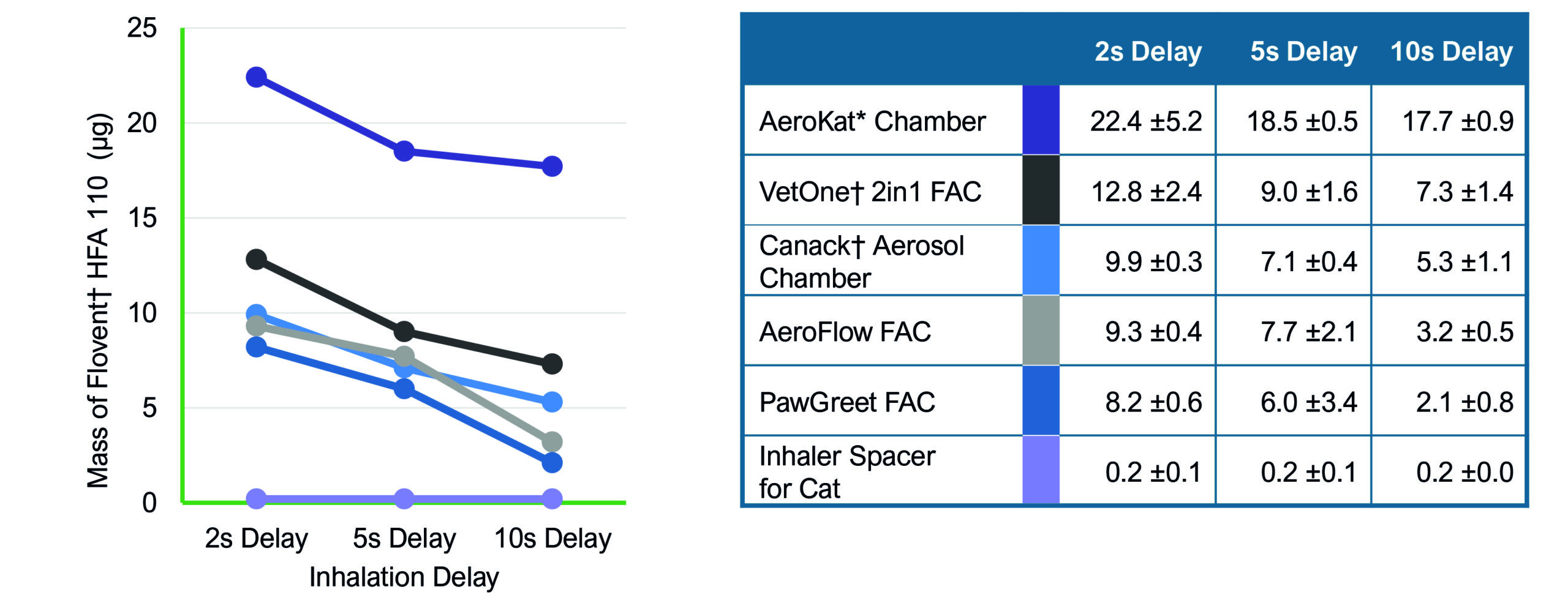

The study employed a fluticasone propionate MDI (Flovent HFA 110ug) to assess various commercially available chambers. Each chamber underwent evaluation using a breathing simulator that was programmed to replicate the breathing pattern of a cat, with parameters set at a tidal volume of 50ml, an inspiratory to expiratory ratio of 1:2, and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute.

To simulate real-life usage scenarios, coordination delays of two, five and ten minutes were introduced between the actuation of the MDI and the commencement of inhalation, thereby mimicking situations where there may be a delay before the cat starts to inhale.

The study revealed substantial variations in the amount of medication delivered by different inhalation chambers. Among the tested devices the AeroKat® Chamber (Figure 1) was the top performer, consistently exhibiting superior drug availability across all three time intervals. At the ten second mark, the AeroKat® Chamber’s drug availability was more than twice that of the other chambers (Figure 2) This superior drug availability is likely to translate into improved clinical outcomes.

Using poorly designed, lower cost spacers may be tempting to owners faced with rising costs. However, inefficient spacer design is likely to lead to poorer control of clinical signs as lower concentrations of medication are delivered than expected. Not only will this translate into increased medication costs through wastage, but poor response to inhaled therapy will also increase the likelihood that systemic medication will need to be used long term, leading to potential co-morbidities such as diabetes and pancreatitis, and further associated costs.

What does this mean for clinicians?

With new products entering the veterinary marketplace and increasing access to online selling, chambers need to be evaluated in order to validate drug delivery performance. Without this information, chambers that appear similar but perform differently may result in some patients not receiving the prescribed dose, increasing the risk of poor disease control and ongoing clinical signs.

AeroKat® Chamber features

- Two mask sizes to cater for all sizes of cat and face shapes

- Anti-static chamber increases drug delivery efficiency by up to 40%1

- Low-resistance valve tailored to respiratory flows of cats

- Keeps medication in the chamber, but…

- …still sensitive enough to open during respiratory distress

- Longer holding times to allow time for smaller lung capacities to empty the chamber

- Flow-Vu® indicator confirms proper mask seal and helps track breaths taken

For more information on the AeroKat® Chamber and the management of respiratory disease in cats, dogs and horses…

References

- Trzil JE (2020). Feline asthma: diagnostic and treatment update, Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 50(2): 375-391.

- Venema C et al (2010). Feline asthma: What’s new and where might clinical practice be heading? J Feline Med Surg 12(9), 681-692.

- Talavera-López J et al (2023). Comparative Study of Inhaled Fluticasone Versus Oral Prednisone in 30 Dogs with Cough and Tracheal Collapse, Vet Sci 10(9): 548.

- Nagel M et al (2020). Impact of spacer design on respiratory drug delivery and potential drug cost implications, American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine.