19 Aug 2019

Alastair Mather and Jon Hall discuss the initial presentation of this issue in canine and feline patients, as well as decision-making for surgery.

Image: © 5second / Adobe Stock.

Cats and dogs commonly present with urethral obstruction as an emergency – and males are more usually affected as a result of anatomical differences.

These include a longer urethra and considerable narrowing of the urethral lumen in the cat penis and dog os penis. Additionally, obstruction at the ischial brim can occur in dogs due to the looping of the urethra over the caudal pelvic floor.

The majority of urinary tract obstructions in cats are either a sequelae to FLUTD, which predisposes to urethral plug formation and/or urethral spasm, or from uroliths1.

Despite a significant decrease in the incidence of urinary obstruction in male cats in recent years due to effective palliative management2 – for example, increased water intake, diet, reduced stress and access to the outdoors – urethral obstruction still affects between 18% and 58% of FLUTD cats3. Strictures – possibly as a result of previous episodes – and neoplasia are other possible causes.

In dogs, urethral obstruction is most commonly caused by urolithiasis. Other causes can include neoplasia, prostatic disease, trauma and bladder herniation associated with perineal hernia.

Recurrent obstruction episodes in either species are not uncommon and result from uncontrolled or untreatable underlying disease.

The most common clinical sign associated with urinary obstruction in both cats and dogs is stranguria (straining to pass urine). Particularly in cats, owners often confuse this with faecal tenesmus or constipation.

Other clinical signs include dysuria (pain on urination), haematuria (blood in the urine, which may not be visible grossly), pollakiuria (increased frequency of urination) and periuria (urinating in inappropriate places)4.

Animals can present lethargic, obtunded or collapsed; triage of the major body systems is prioritised to direct emergency treatment prior to taking a complete history and performing a full clinical examination.

A thorough physical examination may reveal a large, tense bladder (easily palpated in cats and often noted in dogs). If this is not immediately obvious, point-of-care ultrasonography can be used to quickly assess bladder size or detect free abdominal fluid.

Appraisal for signs of hypovolaemia (increased heart rate, poor pulse quality and reduced blood pressure) is essential and may indicate an immediate requirement for IV fluid therapy bolus resuscitation.

An initial clinical pathology emergency database generally includes PCV and total solids (to help elucidate hydration status), urea and creatinine (generally increased), and serum electrolyte assay. Hyperkalaemia is common and life-threatening.

Initial therapy will often involve emergency administration of calcium gluconate to stabilise the heart cell membrane action potential threshold and isotonic crystalloid fluid resuscitation. Use of IV glucose can also reduce serum potassium levels, but it is the authors’ preference to resolve the obstruction to rapidly facilitate a natural subsequent improvement, rather than begin, for example, insulin or bicarbonate administration.

A full description of appropriate medical stabilisation is beyond the scope of this article.

Once emergency stabilisation has been performed, it is necessary to relieve the distended urinary bladder as soon as possible, while, ideally, eliminating the obstruction (even if only temporarily). Therefore, the first approach should always be to attempt passage of a transurethral urinary catheter – ideally achieving both of these aims.

The animal is likely to require sedation or light general anaesthesia (unless severely obtunded); therefore, given the likely concurrent compromised cardiovascular status, agents that are minimally cardiorespiratory depressant should be chosen.

Pain relief is paramount – so, for cats, opioid/benzodiazepine combinations are a good first choice. Ketamine is also useful, but should be avoided in cats with suspected renal damage (for example, long duration of obstruction) due to its renal elimination5. Panel 1 details specific combination options in cats.

For dogs, general anaesthesia will generally be necessary; use an opioid/benzodiazepine premedication (for example, 0.2mg/kg methadone and 0.2mg/kg to 0.3mg/kg midazolam), followed by induction with either propofol or alfaxalone.

Tips and tricks for urinary catheter passage in cats and dogs are provided in Panels 2 and 3.

Initial management of intractable urinary obstruction depends on several factors – including the location of the lesion, the cause of the obstruction and owner finances.

Performing a permanent urinary diversion procedure on the first episode is rarely necessary, but, pragmatically, may be justified if the owners are not able to afford a two-stage approach or the cost of repeated urinary obstruction episodes. It may also be justified if the animal has a condition that makes repeated episodes highly likely (for example, a Dalmatian with ammonium biurate crystals, or any animal with urethral strictures).

Distinguishing mechanical from functional obstruction can be helpful in deciding whether medical or surgical intervention is more likely to be successful.

Placement of a cystostomy tube is indicated when a urethral obstruction cannot be cleared medically, or if urethral or bladder trauma/surgery has occurred and a transurethral catheter cannot be placed for some reason.

Placement buys time for successful medical management of lower urinary tract obstruction and inflammation, with the intention of preserving the normal urinary tract anatomy longer term, or can be used to stabilise a patient prior to further surgery or referral.

This is a simple technique that involves placing a transabdominal Foley catheter or de Pezzer (mushroom-tipped) catheter into the bladder. It may be performed as an emergency procedure via a flank approach, or off-midline via standard midline coeliotomy (particularly if the patient is having a concurrent cystotomy procedure).

The tube should be left in place for 10 to 14 days after placement to ensure adhesion between the bladder and body wall, to avoid intra-abdominal urine leakage on removal.

Potential complications include uroabdomen, nosocomial infections, accidental dislodgement and stomal inflammation/infection.

Antibiotic treatment should generally be avoided while a cystostomy tube (or urethral catheter) are in place, although confirmed urinary tract infection (UTI) or the presence of struvite urolithiasis (often secondary to UTI) will likely necessitate broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy.

Ideally, a urine sample should be submitted for culture once the tube/catheter has been removed and any relevant bacterial infections treated at this stage. Cystotomy tubes are generally well tolerated.

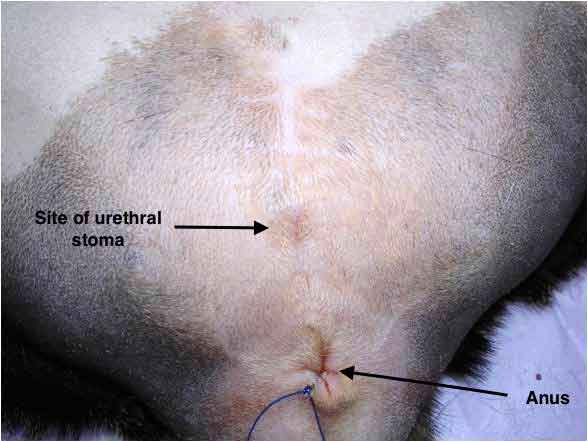

The process of carrying out a perineal urethrostomy (PU) is illustrated in Figures 1a to 1f.

PU is the most common procedure used to permanently bypass the narrow feline penile urethra. The wider pelvic urethra is freed from tough attachments to the pelvic floor, using cautious sharp and blunt dissection ventral to the penis. The penis is amputated and the urethral mucosa meticulously apposed without tension to the skin.

Because only the narrow penile urethra is eliminated, mechanical or functional obstructions further cranial than the penis will not be treated. It is, therefore, imperative that retrograde positive contrast urethrocystography is performed to ensure penile amputation will resolve the problem.

The surgery is well described in textbooks3,7, but some key points are worth highlighting:

Having a urethral catheter in place is essential. If this cannot be placed retrograde then antegrade placement – via cystostomy or a percutaneous Seldinger over-the-wire technique – can be performed. Performing cystostomy and “upside down” PU can be performed on a patient in dorsal recumbency, with the hindlegs tied cranially.

It is vital the structures that attach the penis to the pelvis are released to minimise tension on the urethra/skin anastomosis; the ventral penile ligament, ischiocavernosus muscles and the remnant of the retractor penis muscle. Dorsal dissection is minimised to preserve urethral innervation. Inserting a finger into the pelvic canal ventral and lateral to the penis can help locate residual tough soft tissue attachments.

Dissection to the level of the bulbourethral glands will allow the (wider) distal pelvic urethra to be sutured to the skin, creating a larger stoma. Perineal skin should be perfectly apposed to the urethral mucosa, as multiple gaps will heal by second intention with granulation tissue and consequent contraction leading to stenosis, which risks closure of the newly formed stoma.

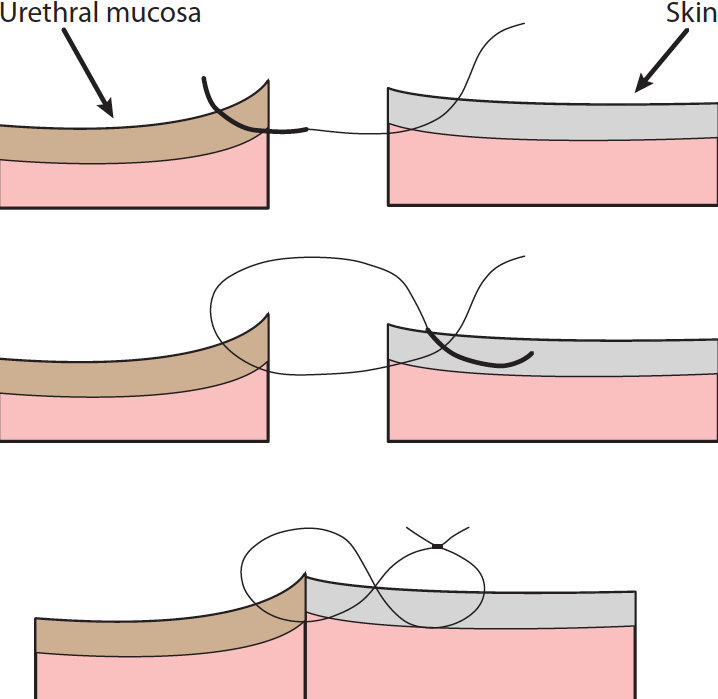

Figure of eight sutures (Figure 2) are a useful way to ensure the knot does not overlie this junction and cause irritation.

Non-absorbable sutures cause less tissue reaction than absorbable sutures. This reduces inflammation and, while they must be removed (often under sedation), this means any irritation is immediately resolved and the surgical site can be carefully appraised.

Appropriate dissection and anastomosis, as described, will reduce the likelihood of urine extravasation into SC tissues, which results in cellulitis and wound dehiscence, and, therefore, further increases the likelihood of stricture formation.

Post-obstruction diuresis should be expected, so monitoring bodyweight as a proxy for total body water content – as well as fluid intake versus loss – is important (for example, urine output, estimate of insensible losses, and weighing incontinence pads or the litter tray).

Serum electrolyte monitoring is also important – particularly potassium, since total body potassium can be low despite high serum potassium at the time of obstruction.

An indwelling urethral catheter is not recommended due to the risk of irritation and ascending infection, but is sometimes necessary if concurrent severe urethral spasm occurs.

Common early complications include haemorrhage, wound dehiscence and SC urine extravasation. Functional obstruction from urethritis is also not uncommon, which, although undesirable, may necessitate the passage of a urinary catheter for another 24 to 48 hours if the cat is unable to pass urine.

Use of smooth muscle relaxants (for example, prazosin 0.25mg to 1mg/cat PO every 8 to 12 hours8) are often routinely used postoperatively (monitoring for hypotension).

The cat should be observed successfully voiding urine for between 24 and 48 hours in the hospital before being discharged. Urinary incontinence is occasionally seen, but is temporary.

The most serious potential complication is stricture formation (Figure 3), which generally occurs around 7 to 10 days postoperatively. The use of urinary catheters, self-trauma and imprecise surgical technique (excessive tension on the urethra-skin anastomosis and inadequate apposition of skin to mucosa) are associated with increased risk of this occurring9.

Recurrent urinary tract infection is the most commonly reported late postoperative complication (between 10% and 33% of cases)9. Urinalysis and bacterial culture have been recommended empirically by some at regular intervals up to 12 months postoperatively9.

It is important to remember PU does not treat the underlying FLUTD/feline idiopathic cystitis that is the cause of urinary obstruction by cellular and protein plug obstruction of the penile urethra in the first place. Recurrent UTI is a feature of these underlying diseases, which may not necessarily be potentiated by the surgery. Ongoing management of lower urinary tract disease long term is essential.

A prepubic urethrostomy involves the anzastomosis of the proximal urethra to the ventral abdominal skin cranial to the pubis. This is considered a salvage procedure following proximal urethral trauma, stricture or failed PU.

Complication rates are high, and include incontinence, urinary scalding, skin necrosis and stenosis.

As in cats, a tube cystostomy may be done to temporarily relieve bladder tension in dogs until the animal is stable enough for definitive surgical treatment.

A urethrotomy may be performed to remove calculi or facilitate passage of a catheter into the bladder.

There is a significant risk of postoperative urethral stricture – so for calculi that can be flushed back into the bladder, a cystotomy is always preferable.

Urethrotomy may be performed in the prescrotal or perineal region, depending on the location of the urolith, but given that stones tend to lodge at the base of the os penis, the prescrotal region is generally considered the best site.

The urethra is more superficial and surrounded by less cavernous tissue in this location – and should a clinically significant stricture develop postoperatively, a scrotal urethrostomy may be performed.

Interestingly, a novel surgical approach has been described where the penis is extruded and an incision made directly over the caudal aspect of the os penis10. Haemorrhage was reported to be minimal and incisions healed quickly by second intention.

Scrotal urethrostomy (Figure 4) is the location of choice for the formation of a new stoma that bypasses the narrow penile urethra.

As for cats, plain radiography and retrograde urethrocystography are mandatory to ensure the urethra proximal to the intended stoma is not compromised. Indications for this surgery include11:

The procedure is well described elsewhere3,7,11.

PU is located at a site with a narrower urethra and increased risk exists of urine scalding postoperatively, since the stoma will not be located at the most dependent location when the dog squats to urinate. It should be avoided unless severe damage or stricture is present at, or proximal to, the site of scrotal urethrostomy.

Urinary obstruction is a common and potentially serious emergency presentation in general practice. Appropriate medical stabilisation and unblockage is essential, and should be performed as a matter of urgency.

Surgery is rarely indicated on the first case of obstruction, but should be considered for recurrent cases where medical management has failed, or, pragmatically, when finances or a high likelihood of recurrence is expected (for example, stricture, or expected predisposition to form uroliths).

Some drugs mentioned in this article are not licensed for veterinary use.