24 Jan 2025

Manuel Pinilla DrMedVet, CertVDI, DipECVDI, MRCVS discusses the appropriate times to use these methods for fast and cost-effective results.

Image: © OlgaPix / Adobe Stock

Medical imaging is frequently an essential component of diagnosis in veterinary practice.

Access to advanced imaging modalities has rapidly increased, from the domain of teaching hospitals to private referral practice, and now in first opinion practice. This provides the opportunity for more animals to benefit from the increased diagnostic potential these modalities offer.

In this brave new world, increasing availability of helical CT in veterinary medicine has resulted in advancements including real-time angiography, 3D reconstructions and virtual endoscopy (Ohlerth and Scharf, 2007).

However, access has often outpaced the spread of expertise and experience to make best use of advanced imaging, with a shortage of radiologists and radiographers in practice. This article explores the decision pathways to aid appropriate modality selection and ensure imaging supports the best clinical outcome for the patient.

With entire textbooks devoted to imaging different body areas according to species, and continuous advancements in our understanding and use of various modalities, exhaustive recommendations are beyond the bounds of this article.

Rather, the author will discuss a solid framework for imaging decision-making that takes into account patient, client and practice factors, to support the best patient outcomes in the clinical setting.

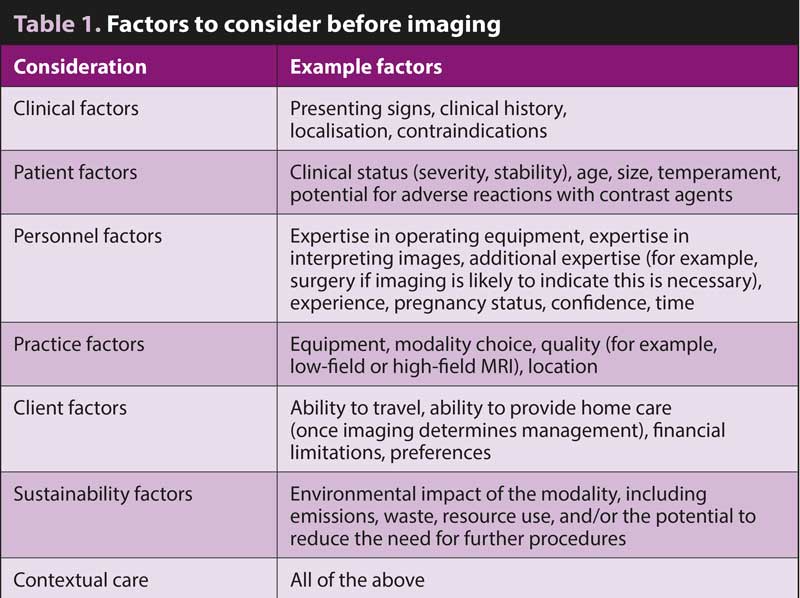

Before embarking on any imaging procedure, it is important to consider several factors that inform appropriate contextual care (Table 1).

Clinical factors are informed by taking a thorough patient history and performing a full clinical examination to localise the area of interest, for example.

Patient factors, such as suitability for prolonged anaesthesia, may result in shorter procedures being preferable, or a small size may warrant higher spatial resolution imaging.

Personnel factors are key, with familiarity and expertise in a particular modality often resulting in more accurate imaging and diagnostic utility. Increased confidence in diagnosis is important for clinicians and has been linked to reduced mental stress, and may reduce anxiety/imposter syndrome that can contribute to burnout (Bhama et al, 2021).

The type of equipment available includes not only modality choice, but the specifications of the machines; for example, whether an MRI machine is low field, medium field or high field impacts the image resolution. Similarly, cone beam CT is excellent for dental imaging, but has reduced utility for larger body areas compared to multi-detector CT. Outpatient imaging may also be an option depending on the location of the practice.

This also depends on the client factors, such as ability to travel and affordability and choice. Explanatory materials outlining the difference in diagnostic utility to the clients and the reasons for imaging recommendations help to support informed client choice.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that each member of the veterinary community has a responsibility to help the industry move collectively towards achieving net zero emissions. Imaging modality choice impacts the environmental footprint of a hospital, and where more than one modality choice may be acceptable to meet patient needs, environmental impact should also be considered (Alshqaqeeq et al, 2020).

Due to the multifactorial and complex nature of imaging decision-making, simple algorithms are rarely sufficient to support clinicians in scenarios in practice. However, a question-based framework can provide a solid basis for good decision-making, considering the advantages and disadvantages of each modality.

Clinical evaluation of diagnostic tests focuses on three key questions:

In the clinical scenario, additional questions concerning the patient, client and practice team should be considered

as follows.

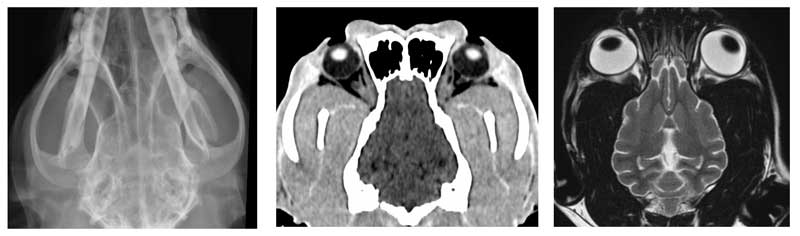

It is beneficial to consider all imaging modalities that may be used and their advantages and disadvantages for the anatomy in question; for example, when considering the head, dental x-rays provide exceptional detail for the dentition of dogs and cats. However, for rabbits, which often have involvement of the sinuses and nasolacrimal duct, CT gives greater spatial resolution of the overlapping structures that are difficult – if not impossible – to differentiate on x-rays.

Where neurological involvement is suspected, MRI is the modality of choice for assessing brain parenchyma. This leads us to consider the next question.

Regrettably, imaging tests rarely result in a definitive diagnosis, but rather a modified list of probabilities.

Potential problems with excessive use of imaging include false-positive diagnoses, detection of incidental findings and over-diagnosis, all of which may contribute to a negative benefit to the animal (Lamb, 2016).

Radiological diagnostic accuracy significantly increases when clinical information is provided, as well as increasing confidence in the diagnosis (Arruda Bergamaschi et al, 2023). Therefore, rather than hoping for a diagnosis to be revealed, it is important to have clarity over the specific clinical question (or questions) to be answered by imaging.

Selecting the modality to answer these questions quickly and cost effectively is often the best option; for example, if you suspect elbow dysplasia, CT is widely recognised as the modality of choice. However, if you want to rule in or out a fracture of the same region, x-ray may be sufficient in most cases.

Patients may present with clinical signs and history that cannot be narrowed down to specific questions with clinical examination and ancillary tests, such as blood and urine samples. In these cases, x-rays and/or ultrasound would be an appropriate first step to image whole body areas (skeleton, thorax and abdomen), rather than proceeding straight to advanced imaging.

Where clinical possibilities are broad, cross-sectional imaging is not recommended for “body scanning”, such as diagnostic screening of entire regions of anatomy to narrow down a broad list of differential diagnoses. The level of detail from cross-sectional images risks revealing abnormalities that are not relevant to the presenting complaint, asking more questions than it answers.

This potentially results in the need for additional, unnecessary testing for exploring “rabbit holes” to confirm the nature of these findings, detracting time and resource away from the underlying pathology and potentially negatively impacting patient welfare.

When determining cost, all factors – including chemical restraint, contrast media, and radiology reporting costs – should be considered. While advanced imaging is typically more expensive, it may save time and reduce the need for repeated or ancillary testing by aiding more rapid diagnosis, proving more cost effective overall.

If in doubt, seeking expert input from a radiologist to help determine the most appropriate imaging modality within the full context may save time and reduce cost.

Financial implications of the next steps should also be considered prior to imaging. If patient and owner factors would prohibit certain treatment options, and the imaging procedure is answering the question about which option to recommend, will it actually impact the outcome for the patient?

Contraindications for imaging may include suitability for lengthy anaesthetic – particularly with MRI.

Consideration should also be given to the contraindications for the use of contrast agents where these would be indicated; for example, oral barium for x-rays where gastrointestinal perforation is a possibility, or gadolinium in MRI where a risk exists of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis or allergy.

It may also include avoidance of CT with high levels of ionising radiation in a pregnant animal – especially early in pregnancy, due to the risk of fetal abnormalities (Benjamin et al, 1986).

Frequently, more than one modality may be appropriate in a given scenario when all factors have been considered; for example, lower respiratory tract symptoms could be grossly assessed by x-ray, or in more detail through CT.

If x-rays are performed that indicate the need for further CT, one may argue CT would have been a better first choice. On the other hand, CT may reveal a straightforward finding that would have been detectable on x-rays.

Here, an open discussion with the owner of the pros and cons of each modality to reach an agreed decision is the best option. In all clinical scenarios, the true art of good veterinary medicine is good communication, expectation management and shared decision making.

The single most important question to consider for any procedure (imaging or otherwise) is how likely it is to affect patient outcome.

If the imaging answers the clinical question, how will this change recommended patient management and is this likely to be feasible? For example, if a high-grade malignancy has been detected on palpation, confirmed via aspirates and the owner has indicated they would not proceed with treatment, is imaging necessary to confirm the extent of internal involvement?

Conversely, if a space-occupying lesion in the cranial cavity is suspected and the owner is keen to pursue all treatment options, MRI may reveal a benign lesion amenable to surgical cure.

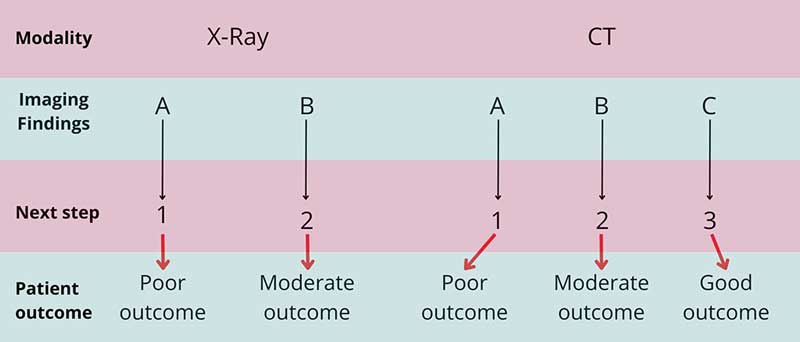

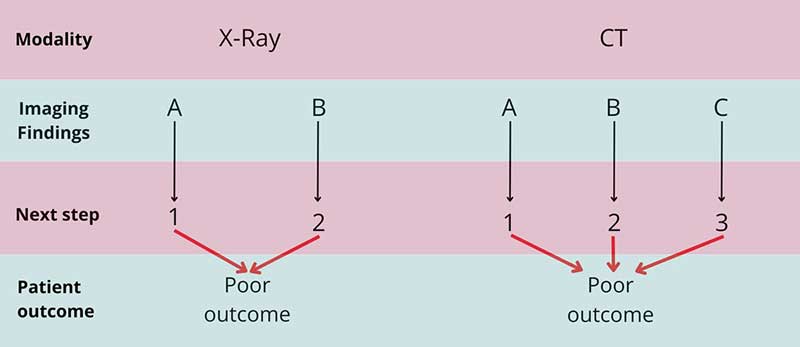

In these cases, it can be useful to sketch out the potential findings for each modality, then consider how each will impact ongoing management recommendations, and whether these recommendations lead to different potential outcomes. This can also provide a sound basis for discussion with the owner.

In Figure 1, CT may lead to more potential treatment options and a better outcome for the patient. However, if the third treatment option was beyond the bounds of affordability for the client, the patient would have no additional benefit of CT over x-ray. In Figure 2, regardless of imaging modality choice and findings, the outcome for the patient is poor, and the use of any imaging procedure should be questioned.

Examples of x-ray, CT and MRI scans can be found in Figure 3.

Choosing an imaging modality is a complex and multifactorial decision-making process.

Where any doubt exists over the most appropriate imaging for a patient, seeking expert advice earlier in the diagnostic process may help to reduce time, cost and unnecessary imaging procedures, and improve confidence of both the clinician and the client.

Following the rapid increase in the number of first opinion practices installing CT and the desire for increased support and training in appropriate use, VET.CT has produced a series of short videos to explain and aid appropriate case selection for CT scans (tinyurl.com/4fauc9fv).

Clinical training often focuses on the accuracy of diagnostic imaging. However, the most important consideration for any diagnostic test is whether it improves patient outcomes. Imaging procedures with the greatest diagnostic impact lead to improved patient outcomes within the bounds of contextual care. Rather than thinking about an imaging procedure in the clinical pathway in isolation, decision-making should consider how each step may affect the ultimate outcome for the patient.

With outcomes in mind, additional factors including time and cost efficiency, and clinical expertise in imaging, should inform recommendations to clients for the care of their pet.

In every clinical scenario, the primary concern should be advocating for the health and welfare of animal patients.