18 Jul 2017

Victor Chua and Nael Taher on how cost of childcare is contributing to growing problem of staff retention.

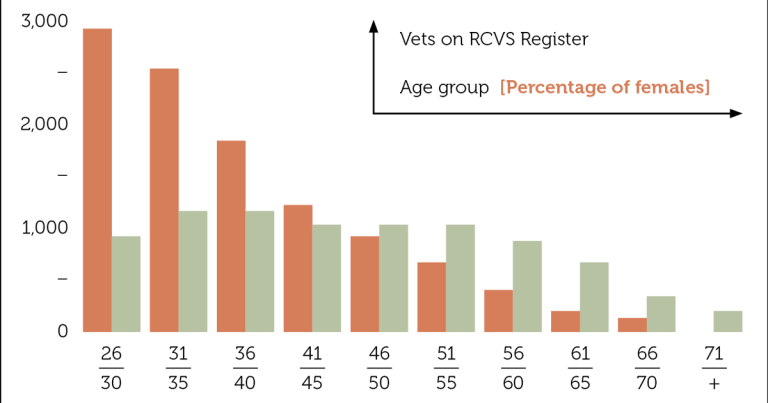

Figure 1. Numbers of practising vets on the RCVS Register by age and gender.

Discussion about the impact and implications of the feminisation of the veterinary profession is commonplace these days, and barely a congress goes by when this is not the subject for fierce debate.

The shifting gender balance of the veterinary profession is well known – 80% of veterinary students today are women. But what is less well known and publicised is the low retention rate of female vets.

Figure 1 charts the number of vets on the RCVS Register by gender and age. Roughly 1,000 male vets are seen in each five-year band between the ages of 26 to 55, with a drop to 800 in 56 to 60 and 600 in the 61 to 65 age bracket as vets retire.

But look at the attrition rate for female vets. From 2,800 vets aged 26 to 30, the number drops to 2,500 aged 31 to 35 and 1,800 aged 36 to 40. In the next cohort of 41 to 45, there are only 1,200 female vets. In the older age cohorts, part of the reason for the smaller number of females is due to a more even gender balance when they attended veterinary school; in the late 1990s, many had an even split between men and women. But the numbers are still stark – half of female vets in practice are aged below 35.

We believe the economics of childcare play a big part in this. We calculated what a full-time vet, working a 45-hour week with an hour each-way commute, would need to earn to have a nanny cover childcare at £9 per hour. The answer was £37,000 – pretty much what a small animal vet with five to 10 years’ postqualification experience commands. In other words, no financial reason exists to go out to work.

Of course, less expensive ways are available to look after children at home than a nanny – for example, nurseries and nanny sharing. But, with the average working week (including overtime) for a vet being 60 hours1, many nurseries cannot cope and nanny sharing only works in some circumstances.

What could plausibly change these economics? It is unlikely nanny salaries will fall, or a future government change employment taxes significantly. So, what would need to happen for veterinary salaries to go up? In our view, it would need:

Veterinary salaries are poor compared to medics. But while the commonalities in education and training are self-evident, in terms and conditions of employment they could not be more different, with the NHS being a state employer with salaries set centrally and national pay scales. NHS GPs have some leeway over their costs, but their revenues, services provided and opening hours are driven by standard contracts.

Vets should look to other professions, such as law and accounting, that are dominated by independent practice. These have been reasonably successful in restricting entrants to a level commensurate with demand – BVA and British Veterinary Union take note.