2 Mar 2021

Mary Fraser BVMS, PhD, CertVD, MAcadMEd, CBiol, FRSB, FHEA, FRSPH, FRCVS, discusses how important the art of conversation between vet and client is when deciding what direction to take for an animal and, using results from an online questionnaire, enlightens readers in owner opinions of making decisions in a clinical setting.

Image: © Iryna / Adobe Stock

Working in general practice can be a challenge. Not only do you need to know lots about different animals and the myriad of diseases they can get, every owner who walks into the practice is different.

Some will do anything you tell them, while some will arrive with a printout from Dr Google and tell you how to do your job. Most of them will be somewhere in-between.

As a new graduate, people can be one of the most challenging parts of the job. I certainly left university with a list of questions to ask owners to obtain a clinical history, but absolutely no knowledge of how to work with people or communicate with them. The art of conversation has been learned the hard way through working with owners and colleagues.

Modern practice also gives vets and owners many choices. Medical or surgical cases that might not have been treated 20 years ago can now be dealt with; conditions that would once have meant euthanasia can now be treated or managed.

Decisions need to be made by both physician and owner, in the best interests of the animal. The ideal consult would involve the vet and owner. Some owners may want to be guided by the vet, but some will want to feel that they have to be consulted and make decisions for their animal themselves. Many factors will influence this relationship.

When a dog presents following a road traffic collision, the owner is less likely to be willing to discuss things in detail and may well just want the vet to get on with things. Asking owners to sign a consent form at this time can be difficult enough. From personal experience, where owners were well known to the practice, discussions were easier, and the owner and vet team could work together.

The time available for a discussion will also affect the ability to make decisions, with some owners needing more time to discuss options. While consulting times may be longer now than 20 years ago, rushed Friday evening consults still exist and the pressure of a packed waiting room can influence how much discussion can take place in the consult.

Challenges to the decision-making process also include understanding of conditions and treatment options. The ways in which information is presented to owners may depend on the practice protocol or the condition itself. Depending on the condition, just talking to owners might not be the best way forward.

Some conditions such as atopic dermatitis, arthritis or epilepsy have many different supporting materials online or in paper form, which owners can be directed towards. Other less specific conditions – such as pleural effusion, cat bite abscess or conjunctivitis – may not have the same wealth of information available and owners need to get their information from the vet practice.

The advances in medicine and surgery mean it is possible to do much more for patients now, but a question always exists around how much should be done. Disagreements between owner and vet require a degree of conflict resolution, which then demands good communication skills.

Past experience also affects decision-making, for both veterinary surgeon and owner – especially when it comes to euthanasia. An owner may demand a home visit for a euthanasia because a previous experience in the practice was just too upsetting.

Past experiences of traumatic events play a large part in how an owner will approach a decision. This also applies to the veterinary surgeon. Bad experiences will influence what is or is not done when working with a case.

All of these factors need to be considered when reviewing how decisions are made about cases. An awareness of the factors that influence decisions can lead to removing any bias that is present. Bias can take many forms (Figure 1), and can affect both the owner and the vet/vet team.

Bringing all of this together, 100 owners took part in an online questionnaire to find out more about their opinions of making decisions in practice.

Results were generally positive, with 87% of owners indicating they felt they could always or usually contribute to decisions about their pet’s care, 11% feeling they could sometimes contribute and only 2% feeling they could rarely contribute.

When asked about the factors that influenced their decisions (Figure 1), the most dominant factors were “Advice from vet” and “Chance of a successful outcome” (mode = 5). This was closely followed by the certainty of the outcome, evidence about the condition, their own past experiences of similar cases and their own gut feelings or emotions. The least influential factors were TV/press, social media, costs/finance, and discussion with friends and family.

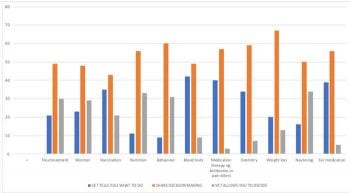

Owners were given a variety of scenarios (Figure 2) and asked if they would prefer to make the decisions themselves, have the vet make the decision for them or share the decision process between them and the vet.

Unsurprisingly, shared decision-making was the predominant answer for all situations. However, a larger proportion of owners did indicate they would like the vet to make decisions for vaccination, blood tests, dentistry, medication, weight loss and ear medication, whereas more owners wanted to make their own decisions for flea and worming treatments, nutrition, behaviour and neutering.

Shared decision-making is defined by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as the process where health professionals and patients work together (NICE, 2020). This involves a discussion about options, risks and benefits. Communication is essential for good decision-making; any disruption of this can impact on the relationship between vet and client (Coe et al, 2008).

The term “shared decision-making” was used intentionally for this study. In recent years, relationship-centred care has been used in relation to veterinary practice, and focuses more on the development of a connection between owner and vet (VetSet2Go, 2018).

While it is recognised the relationship between owner and vet can be based on past experience, length of time they have known each other or trust the owner has in the vet, this study was not looking at those aspects.

The aim here was to purely focus on the attitude of the owner regarding his or her involvement in making decisions about cases, which will, of course, depend on owner circumstances and personality.

From this work it can be seen that most owners would like to be part of the decision-making process and felt confident in making or contributing to decisions about the care of their pet.

It is possible that people who are more likely to interact with their veterinary surgeon and take part in the decision-making process were also more likely to take part in a study. These owners also did not think that their decisions were influenced by social media. This is an interesting point as it goes against a common perception of veterinary surgeons in practice (VetsDigital, 2014).

Results showed that owners were reliant on the provision of information from their practice. No work was carried out looking at the information that owners wanted. As many owners wanted to make their own decisions about parasite treatment, nutrition, behaviour and neutering; the veterinary practice can play an important role in providing owners with that information, and ensuring that information is current and evidence-based.

This is only an initial study and further work is required to understand better what owners believe is a good consultation where they take part in shared decision-making, but it does highlight the importance of decision-making within a clinical setting from a client’s perspective.