3 Apr 2020

Vet Chris Copeman built one of the first Passivhaus homes in the UK and now he has opened its first Passivhaus veterinary practice.

Staff: full-time vets 6 • registered veterinary nurses 6 • practice administrators 2

Fees: initial consult £24 • follow-up £24

RVC graduate and owner of Bryn Veterinary Centre Chris Copeman is – by his own admission – a bit of a hippy.

And that’s not just because he has a beard and takes soya milk with his tea – this is a man who cares deeply about the world around him.

Chris was the Green Party candidate for Ellesmere Port and Neston at the last General Election, and his passion for the environment has led him to develop a deep interest in eco-friendly buildings. He is also a smart businessman who has a two-site practice that turns over more than £900,000 per year, so he needed to find a way to balance these seemingly competing objectives.

But by using a passivhaus approach, he has managed to build a highly efficient, modern practice that generates more energy that it ever uses, while at the same time making as small a dent on the world’s dwindling resources as possible.

And this is no soulless German block built to satisfy a set of construction criteria; Chris describes his new practice as a “happy building” full of warm, natural materials, where staff, clients and their pets all seem to thrive.

He said: “I am actually a passivhaus consultant and own one of the only passivhaus homes in the UK, so when we wanted to develop this site and build something new, it seemed the best way to go. Yes, you need to do things a bit differently, but the result is a near carbon neutral build footprint and a building that is 10 times more efficient, generates its own power and gives you full control of every aspect of the environment inside.

“In the current climate, we are all thinking about coronavirus, and we know viruses spread in the high and low humidity levels, so it helps to have an environmentally controlled building like this because we’ve got a controlled ventilation system. I can up ventilation levels if I’m worried about possible virus spread, I’ve got control over the atmosphere in this building.”

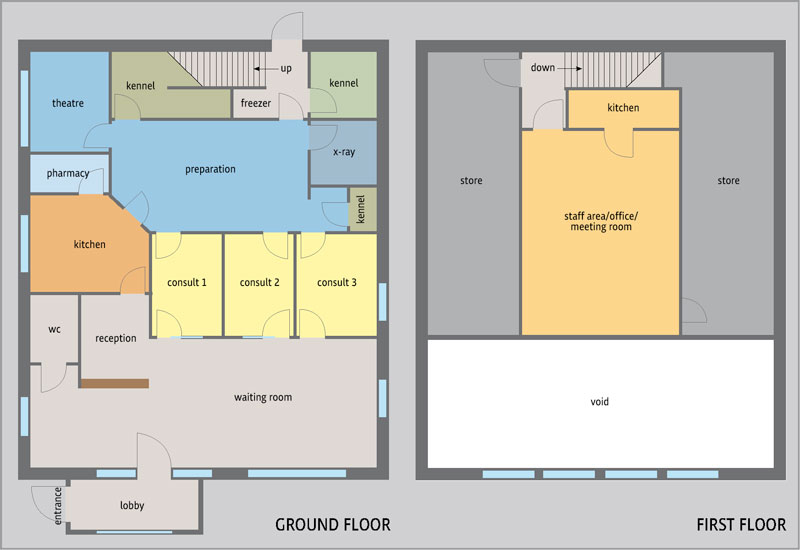

With three consult rooms feeding off a reception space that reaches up to the roof of the two-storey building, the practice is made almost entirely of recycled and sustainable materials, and does not contain a single piece of steel in its construction. Instead of traditional foundations the practice sits on a passive raft platform, essentially a large rectangle of polystyrene that gives the building 360° insulation once construction is complete.

Chris added: “The building has a raft made out of hardcore from the old building, so it’s built using something called a passive raft – this involves a polystyrene raft laid down on to a sand blinding with a lip into which you pour the reinforced concrete floor for the building. You’ve just got a concrete floor that is surrounded by insulation so you’re not having any heat loss from that floor; there’s no thermal bridging.”

The first stage in the building, however, was to put the building design – once developed with the architect – through a sophisticated software package called Passivhaus Planning Package, which calculates energy use of the building using everything from solar orientation and altitude to windows and wall make up.

This information is then plugged into a rather complicated spreadsheet that gives a figure of how much energy that building will use. The goal – under passivhaus guidelines – is a building that uses just 15 kilowatt hours per metre squared, as opposed to traditional buildings that use at least 120 kilowatt hours per metre squared.

Once the software was happy, plans were finalised and approved by the local council and Chris was able to push ahead with his passivhaus plans.

He said: “The type of timber frame used is a twin-wall construction that consists of two sections of 4×2 timber that are held together with bits of timber between them, so it’s like two stud-walls joined together by noggins in between.

“We ended up going with a firm down in Gloucestershire that built the frame in its factory. It’s a specialist passivhaus firm that builds all over the country and it builds in panels that it assembles on site. So this building was put together in panels down in its factory, then a lorry or two was all it took to bring the whole building up, and a crane was brought in that lowered the panels on site on to the passive slab, which was finished at this point, and then it was bolted down to that concrete floor.

“So within a week you’ve got a weather-tight building. It’s an incredibly fast building method and this was happening in late autumn, so not very good weather conditions. It was quite incredible to watch this team that uses nail guns largely to nail the panels in place.”

With the frame up, Chris then had to put a membrane on the roof, put all the quadruple glazed windows in, finish off the cladding on the outside and install the solar panels.

The timber structure had already been insulated by the construction crew, who used cellulose-based insulation that can be pumped into the walls and roof. The insulation acts as a preservative for the timber and is incredibly fire-resistant.

But all that insulation would be a waste of time if the building were not air tight. Chris explained: “If you insulate a building well, but you don’t deal with air-tightness, you get thermal bypass, so air draughts will just carry cold air into a building and your building won’t be as efficient. So this is an incredibly air-tight building, which means you’ve got control of air within the building.

“A heat-recovery ventilation system is then put in at the next stage through internal voids in the building. In the floor space there is lots of ducting going round, and that means you can supply and extract air from exactly where you want it in the building and you can have cross-flow of ventilation, so we have a cross-flow of ventilation going from the operating room, across a prep room and out to the kennels.”

The ventilation system at Bryn Vets provides a controlled amount of ventilation to every room in the building and allows Chris to extract air from “wet” rooms, such as operating rooms and kennel rooms, to create a healthy air flow and reduce the risk of infection.

Once extracted, air gets taken back to a super-efficient heat exchanger where it is filtered coming in and out to remove pollens. The heat exchanger will take the heat out of the stale air being taken out of the building and pass it into the fresh air, without anything else being exchanged.

The exterior of the building is clad with larch timber, which has a really high oil content and is good for 20 years, while on the inside of the building Chris used a product called Fermacell.

He added: “These [Fermacell] boards are made from recycled gypsum and are much stronger, much harder and much more fire-resistant than plasterboard. They are a bit more expensive, but they are much tougher than plasterboard. Clay-based paints have been used on all the walls as they contain lower levels of volatile organic compounds, while all floors are made from sustainable bamboo.”

In the end, the practice cost £400,000 to complete, including the demolition of the old pub that stood on the site and the cost of the new building.

It is a relatively modest sum for such a technically advanced practice and, according to Chris, his investment has already begun to pay off.

He said: “We just moved into this building in January, which is typically a quiet month in the veterinary world for small animal work, but it was the busiest month we’ve ever had – we did £106,000.

“I think it’s something for the area as well. It’s the first passivhaus building like this in the UK. What I’ve heard from the neighbours is you’ve put a really nice looking building here, you’re really doing something for the area, and it’s a part of the country that hasn’t always had a lot of outside investment and I think it’s quite positive for the area to make this investment here.”

Bryn Vets is a strictly first opinion practice, with six vets splitting their time between two sites; the second is a branch surgery in Golborne, four miles from Wigan.

But it is the new site his team seems to thrive in, despite a pub having to make way for its creation. Chris said: “It seems a bit wrong knocking a pub down, doesn’t it? But we are over that now and we did reclaim the old bar for our reception desk, plus some other bits and pieces.

“I think the team appreciates that it’s a much nicer building to work in – both in the space and the environment – and the lighting is much nicer to work in in here. It makes it a really nice building to work in. Nobody even wants to go back into the old building, because it just feels a little bit squalid in comparison.”

While Chris’ practice now generates enough solar power to justify three phase electricity and enough surplus to sell power back to the National Grid, Chris may not be finished with his dream eco-friendly practice just yet.

He said: “Not sure we’ve got room for the wind turbine I have been thinking of adding, though.

“Bryn means hill in Welsh. Because a load of Welsh miners came here 100 years ago to work the mines in this area, so we’re quite high up, we’ve probably got fairly good wind speed here.

“I don’t know what the planning authorities would think about it, though. It might be a bridge too far for the neighbours, too.”