14 Sept 2020

Angus Yeomans BVSc, BSc, MRCVS and Safia Barakzai BVSc, CertES(SoftTissue), MSc, DESTS, DipECVS, FRCVS detail the case of a three-year-old Thoroughbred that presented with this symptom following intermittent colic.

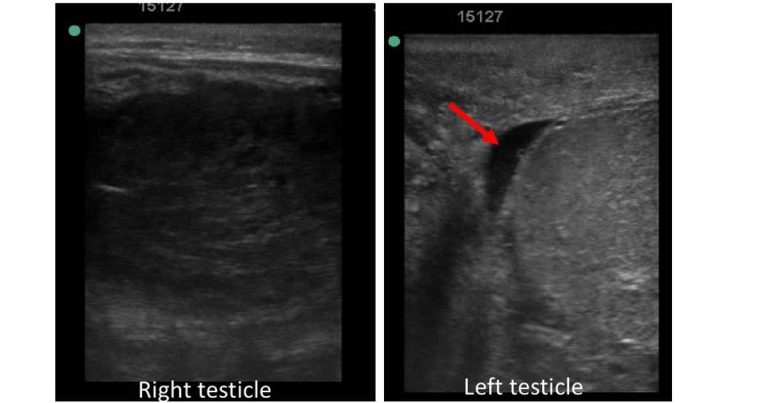

Figure 2. Comparison of echogenicity of the testicular parenchyma of the right and left testicles. Note a small amount of hypoechogenic free fluid within the vaginal tunic on the left side (red arrow).

This report details the diagnosis and treatment of a three-year-old Thoroughbred colt that presented with scrotal swelling following five days of colic‑like symptoms. Based on clinical, rectal and ultrasonographic examinations, and basic haematological and biochemical analysis, a provisional diagnosis of spermatic cord torsion was made.

Exploratory surgery was performed under general anaesthesia where the diagnosis was confirmed. The colt was not required for reproductive work and, therefore, underwent bilateral orchiectomy. The recovery was without complication and the patient was discharged from the hospital two days postoperatively.

A three-year-old Thoroughbred colt was presented with a five-day history of mild intermittent colic and progressive unilateral right-sided scrotal swelling.

The colt had been initially seen by the referring vet five days previously for mild symptoms of colic and had been managed medically.

Slight swelling of the scrotum had been noted at the time; however, no further investigation was carried out at this point. It is true that testicular size of individual stallions may vary markedly, making early diagnosis of mild testicular swelling challenging.

Five days after the initial veterinary visit the colt was re-presented by the trainer due to recurrence of mild colic symptoms and increased scrotal swelling. He was admitted to Hambleton Equine Clinic for further investigation and treatment.

The patient’s temperature, heart and respiratory rate were all found to be within normal limits and, with the exception of visible scrotal swelling, the clinical exam was unremarkable.

Palpation of the scrotal area revealed asymmetrical swelling (Figure 1); the right scrotal skin and SC tissue were very oedematous, and the right testicle felt hard and enlarged on palpation, which elicited mild to moderate discomfort.

Mild oedema of the left scrotal tissues was also present; however, unlike the right testicle, it was possible to easily identify via palpation the body of the left testicle and the epididymis, which had a normal orientation, with the epididymis positioned laterally.

An initial list of differential diagnosis for unilateral scrotal swelling included testicular trauma and associated haematocele, infectious orchitis or abscessation, hydrocele, inguinal herniation, testicular torsion and neoplasia.

In this case only basic haematological parameters were evaluated and were found to be within normal limits: PCV 46%, total protein 90g/L and blood lactate 1.3mmol/L.

Further haematological or biochemical analyses were not performed for cost reasons, given the relatively normal clinical presentation of the patient and the absence of pyrexia, but potentially could have been useful to differentiate between non-septic/non-infectious and septic/infectious processes, including – but not limited to – equine viral arteritis.

Ultrasonographic examination of the scrotum using a 7.5MHz linear probe was then performed. The right testicular region had a small amount of free fluid within the vaginal tunic and marked heterogeneous hypoechogenicity of the testicular parenchyma (Figure 2).

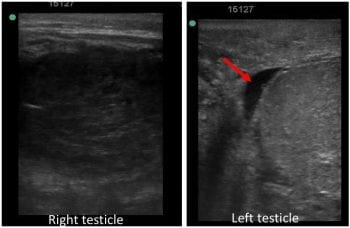

A cylindrical (in cross-section) dilated structure was adjacent to the testicular parenchyma (Figure 3). This was thin‑walled and most of its lumen was filled with hypoechogenic (fluid) material.

No motility of this structure existed when observed for several minutes and, therefore, the structure was thought to be an enlarged epididymis.

Evaluation of the left testicular region revealed normal (homogenous and relatively hyperehoic) echogenicity of the testicle compared with the right and a small amount of free fluid within the vaginal tunic (Figure 2). No other abnormalities were noted.

Rectal examination, performed under sedation with additional IV hyoscine butylbromide at 0.3mg/kg, was unremarkable. Particular care was taken to palpate both inguinal rings carefully per rectum: no intestine was encountered entering the right inguinal ring and, therefore, an indirect scrotal hernia was deemed unlikely (also given the mild colic and ultrasonographic findings).

The case was considered to require relatively urgent surgical investigation. The horse was prepared for exploratory surgery under general anaesthesia, was anaesthetised and placed in dorsal recumbency.

The right scrotal skin was incised approximately 2cm abaxial to the midline raphe for a length of 10cm, and the vaginal tunic was then sharply incised to explore its contents (Figure 4). Some dark-coloured fluid emanated from the tunic as it was incised.

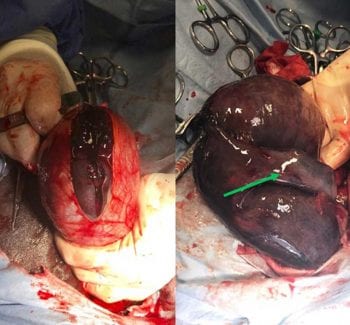

As the right testicle was exteriorised it appeared very enlarged, oedematous and very dark coloured – almost black. When exteriorised fully from the vaginal tunic, a torsion of the spermatic cord of 180° could be seen (Figure 5).

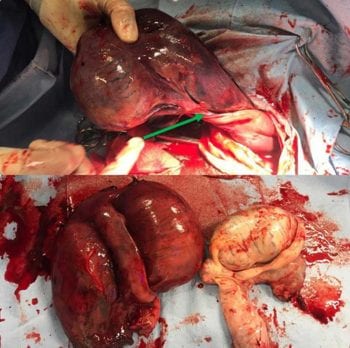

The testis was deemed non-viable, and the spermatic cord proximal to the torsion was ligated and the testicle removed. The owners did not require this horse for reproductive purposes; therefore, the decision was made to also remove the left testicle using a routine closed castration technique. The scrotal incisions were left open to drain.

The horse recovered uneventfully from anaesthesia and made an excellent recovery.

Spermatic cord torsion predominantly affects young adult, non-cryptorchid stallions, although cases of intra-abdominal torsion in cryptorchids have been reported, and are more often associated with neoplasms such as seminomas (Beck et al, 2005).

Torsion of the spermatic cord of less than 180° can be a non-pathological finding, and such cases are not always associated with pain-related symptoms. These milder types of spermatic cord torsion may present intermittently or as a permanent lesion accompanied with more obvious symptoms.

Conversely, torsions of around 180° – such as was seen in this case – result in venous occlusion, and are usually characterised by a unilateral hard, painful testicular swelling and associated scrotal oedema. Colic-like symptoms are usually present.

Given the colour of the right testicle in this case, it is quite surprising this colt was only showing mild colic symptoms and that the testicle was not particularly painful on palpation. True ischaemic necrosis is associated with a spermatic cord rotation of 360° or more, which results in both arterial and venous occlusion, and such horses are expected to present with more acute, severe pain (Pascoe et al, 1981).

Early diagnosis is essential if the reproductive viability of the testicle is to be conserved. It is important to ascertain the reproductive value of the animal from the owner, as this will have an impact on treatment if the testicle is still thought to be viable and on the decision to remove the contralateral testicle.

Where gross scrotal swelling is present, the reproductive viability of the testicle should be considered uncertain, not only due to possible vascular compromise, but also due to the sensitivity of testicular tissue to changes in temperature.

Torsion of the spermatic cord is believed to be associated with anatomical variation in the length of both the caudal ligament of the epididymis and the proper ligament of the testis (Pascoe et al, 1981). These anatomical abnormalities tend to be bilateral.

In addition, the testicles in both equine and canine species lie within a horizontal rather than vertical plane, which is thought to further increase the incidence of torsion.

Diagnosis of spermatic cord torsion is made following interpretation of the history, and both clinical and ultrasonographic examinations. The clinical presentation of spermatic cord torsion may be very similar to that of inguinal herniation.

Symptoms associated with the latter should more closely represent a small intestinal obstructive lesion, with overt colic, distended loops of small intestine on rectal and/or ultrasonographic examination with or without the presence of reflux on nasogastric intubation.

Bilateral testicular enlargement and the presence of pyrexia may help to distinguish orchitis from a spermatic cord torsion. Colour Doppler ultrasound may also be of help in differentiating between orchitis and torsion, with reduced blood flow seen in a case of torsion.

Other differentials for testicular swelling were considered less likely in this case, but include hydrocele and neoplasia. Testicular neoplasms are uncommon within this age bracket (three years old) and in non-cryptorchid horses.

Neoplastic changes to the testicular parenchyma can usually be detected ultrasonographically and are often localised to only a portion of the testicular tissue. A preoperative diagnosis may be made via fine needle aspiration. This diagnosis could not be definitively ruled out preoperatively in this case, but was considered less likely.

A hydrocoele is caused by an excess of free fluid within the tunica vaginalis; it is usually seen in castrated males, but can also be seen in entire males. The fluid/swelling is non-painful, reducible and associated scrotal oedema is not present.

Ultrasonography of a hydrocoele would clearly demonstrate a large amount of hypoechoic fluid surrounding the testicle, with a normal appearance of the testicular parenchyma.

Bilateral castration, as performed in this case, is the most commonly performed treatment for testicular torsion, alleviating symptoms and preventing recurrence. In cases where breeding potential is of importance, unilateral orchiectomy or orchiopexy may be considered.

It should be borne in mind that once a stallion has had a unilateral torsion, the contralateral spermatic cord is at an increased risk of subsequent torsion (Threlfall et al, 1990; Sells et al, 2002). This is explained by the bilateral nature of the anatomical variation of both the proper and caudal ligaments, which predisposes to spermatic cord torsion.

Therefore, where unilateral orchiectomy or orchiopexy is performed following a torsion event, it might be prudent to also pexy the contralateral testis. It has been suggested a loss of fertility of the contralateral testicle is observed in humans following testicular torsion (Anderson and Williamson, 1990); however, the evidence for this is controversial and beyond the scope of this article.

In conclusion, prompt diagnosis of spermatic cord torsion may be challenging following partial or intermittent torsion, and ultrasonography of the scrotum is a very useful tool in such cases.

Treatment for testicular torsion consists of correcting the torsion and pexy of the testicle (and pexy of the contralateral side) where the testis is still viable; or castration, which can be unilateral or bilateral.