18 Nov 2019

Jamie Prutton discusses such approaches to pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction and equine metabolic syndrome.

A number of endocrinological diseases exist within equids, but as the most prominent are pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) and equine metabolic syndrome (EMS), this article will focus on these.

The diagnosis and appropriate management of either disease can have a profound effect on the prognosis and clinical well-being of the horse – and, therefore, warrant quick and accurate diagnosis to allow for timely implementation of the appropriate treatment modalities.

Ongoing research has led to a multitude of tests being available for both PPID and EMS – therefore, it is imperative the most appropriate ones are used. The Equine Endocrinology Group (EGG; https://sites.tufts.edu/equineendogroup) regularly reviews this information, and produces guidance documents that will lead practitioners through the appropriate diagnostic steps and treatments.

Equine PPID is a neurodegenerative disease seen mostly within the older population of horses. In total, 21% of horses older than 15 years of age were shown to have endocrinological changes consistent with PPID (McGowan et al, 2013), with the average age of horses affected being approximately 20 years depending on the study (Couëtil et al, 1996; Donaldson et al, 2002; Hillyer et al, 1992).

It must be noted that PPID has been recorded in horses as young as seven years old; therefore, the disease should not be dismissed in younger animals (Heinrichs et al, 1990).

The clinical signs of PPID are well known, and often categorised into those associated with early disease and those with advanced disease. Some of the early signs can include non-specific changes, such as variations in demeanour, decreased exercise performance, either hypertrichosis or delayed coat shedding, loss of muscle mass, abnormal sweating, regional adiposity and laminitis.

During the advanced stages of the disease, the early signs will often become more prominent and other additions can include polyuria/polydipsia, recurrent infections, mammary secretions, increased susceptibility to parasitism, and neurological deficits including blindness (McGowan et al, 2013). The close association between PPID and EMS cannot be overlooked, and diagnosis of both should play a role in any examination of suspected endocrinological laminitis.

EMS has been described as the presentation of insulin dysregulation, a predisposition to laminitis (or ongoing laminitis), as well as a phenotype of obesity or abnormal adipose tissue deposition (Frank et al, 2010). Insulin dysregulation (ID) can be seen without PPID, but a subset of PPID patients will have secondary ID. EMS is a result of the interaction between genetic predisposition and the environmental challenges the horse is under.

Horses with a high genetic propensity to EMS will need a relatively small environmental challenge to induce laminitis, while those with a low genetic likelihood of EMS will require a large environmental challenge. As such, all horses have the potential to be affected by EMS, depending on the combination of genetics and environment.

ID will present as either an abnormality in the resting insulin or, more likely, the insulin following a dynamic test.

The diagnosis of PPID appears simple at first glance, but due to a number of confounding factors, it can be difficult in practice. When considering which test to undertake, the clinical case should be separated into those with equivocal/early PPID and those with moderate or advanced PPID (Panel 1).

Early PPID clinical presentation

Moderate to advanced PPID clinical presentation

When obvious clinical concern exists then a resting adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) should be used, but if the case is equivocal it may be wise to use the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) stimulation. When sampling ACTH, the blood should be taken into a plastic ethylenediamine tetra-acetic acid tube, which should be separated and either kept cool or frozen as soon as possible. If freezing samples then centrifugation is essential as false-positive results are seen after gravity separation and freezing.

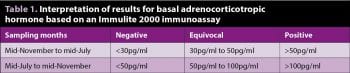

Basal ACTH concentration in plasma is the most easily accessible test available, but is not without its drawbacks. The cut-off values have been debated and various viewpoints exist as to where the exact cut-off should be (Table 1).

The ability to offer weekly reference ranges is now available at Liphook Equine Hospital, thanks, in part, to the ongoing Talk About Laminitis scheme funded by Boehringer Ingelheim. This allows accurate guidance on the appropriate treatment course and clinical relevance of each result. It should be noted that treatment with pergolide should always be based on the presence of clinical signs and age, as well as the exact value on the test.

If the basal ACTH result is borderline (30pg/ml to 50pg/ml in the non-autumn months and 50pg/ml to 100pg/ml in the autumnal period – remember different assays will return different results so the values should be interpreted in line with your reference laboratory) or the horse is showing equivocal clinical signs, then further testing with a TRH stimulation test should be undertaken. Interpretation of the results should be based on the values in Table 2.

The reference ranges for the autumnal period were recently studied, but care should be taken in this period with the interpretation, hence why such a large equivocal area is presented for the autumn. The EEG is not recommending testing in the autumn for this reason.

To undertake a TRH stimulation test, the following procedure should be performed:

Repeat testing, whether it is a basal ACTH or a TRH stimulation, is essential once pergolide treatment has been initiated. Most horses will have responded maximally within one month following initiation of pergolide, but a few outliers can take longer.

If repeat samples are taken early and the results do not reflect complete endocrinological control, the test can then be repeated a further one to two months later to ensure no ongoing reductions in ACTH will be seen at the dose being given.

It should also be noted that repeat tests should be interpreted alongside the reference range for that time of year. In autumn, this can appear as though an increase in the absolute ACTH value exists, although it may fall within the reference range in an endocrinologically controlled horse.

Pergolide is the licensed product in the UK, and initial dosage should be approximately 0.5mg for a 250kg horse and 1mg for a 500kg horse given orally once daily (approximately 2µg/kg every 24 hours). Some horses can show side effects, with the most common being a transient reduction in appetite that can be addressed by temporarily stopping or reducing the dose and then gradually increasing it.

The ACTH should be retested at one to two months, but if concern exists that the response is not adequate, a repeat test can be performed a month later prior to increasing the dose further. If patient compliance is poor then the pergolide tablets can be dissolved (as per the data sheet) prior to administration.

When considering ongoing management and treatment strategies, the cases can be broken into four groups:

Poor responders can be difficult to treat and it is possible to add cyproheptadine (0.25mg/kg every 12 hours) alongside the pergolide or anecdotally splitting the current pergolide dose into every 12 hours treatment does help some patients.

Multiple tests are available for ID – each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Insulin is stable in separated blood for approximately three days, but if a delay in testing will occur then the sample should be frozen. All results should be interpreted in line with the laboratories’ reference ranges as different assays will produce different results and, therefore, absolute numbers are not given in the text. The diagnostic tests and their relative merits are now presented.

A resting insulin test can be useful if the clinician is concerned about using dynamic testing – and a positive result indicates ID. This test has a relatively low diagnostic sensitivity; therefore, if negative, further testing would be warranted. Resting insulin can be used to assess the appropriateness of a diet.

Dynamic testing can be undertaken with an oral sugar test. The recommended protocol requires a period of starvation (3 hours to 12 hours) followed by administration of 45ml/100kg BW of corn syrup syringed into the mouth (gentle warming makes this much easier), with blood samples taken for glucose and insulin at 60 and 90 minutes. Recent work has shown the higher dose of 45ml/100kg – compared with previously advised 15ml/100kg – has an increased sensitivity and specificity, and is therefore recommended.

Dynamic testing can also be performed with the insulin tolerance test. The two-step insulin tolerance test is the only test directly assessing the tissue insulin sensitivity. To perform the test, a basal blood glucose is taken, followed by the administration of 0.1IU/kg of soluble insulin IV with a subsequent blood sample taken 30 minutes later for glucose testing.

Insulin-sensitive horses should have a reduction in glucose of greater than 50%, while insulin-resistant horses will not (Bertin and Sojka-Kritchevsky, 2013). Horses should not be fasted prior to this test – and when performing this test, it is advisable to have access to IV glucose (50%) in case of a hypoglycaemic incident, although this is very rare. Normal advice would be to feed them following the second blood sample.

High molecular weight adiponectin is a hormone produced by metabolically active fat. In non-insulin dysregulated horses, this value remains high, leading to increased insulin sensitivity within peripheral tissue, while a low result indicates an increased risk of insulin resistance. Although not a direct marker of EMS, it is highly correlated with the risk of laminitis associated with ID.

The biggest advantage is it can be taken throughout the day with no need to starve the horse. Monitoring of the values, as with dynamic insulin testing, can be disappointing if excellent weight loss is not achieved. Therefore, retesting should only be undertaken once the owner has achieved good weight loss.

Once a diagnosis of EMS has been made, advising the owner on how to minimise the inherent increased risk of laminitis should be undertaken. The primary treatment is to ensure an appropriate diet is undertaken and the use of scales to weigh food is essential, alongside exercise if the horse is not suffering from laminitis. When considering an obese patient, the initial diet should include:

Following initiation of the diet, the weight should be assessed monthly and the diet adjusted appropriately. Once at an appropriate BW, the diet can be adjusted to maintain a static weight. If considering turning out then it would be sensible to consider a postprandial insulin response as it will indicate the risk of laminitis due to hyperinsulinaemia.

Exercise is essential (unless laminitis prevents it) and it is likely any exercise will be beneficial. If possible then 15 to 20 minutes of trot five times a week will greatly expedite weight loss, as well as resolution of the ID.

If the horse is lean then the diet should be a low glycaemic one, with supplementation of carbohydrates with fat and proteins to ensure calorific needs are met, but reduce the risk of hyperinsulinaemia. Pharmalogical management can help with the treatment of EMS in select patients. Metformin can be used in horses that have a persistent hyperinsulinaemia following managemental changes or if laminitis is severe and precludes including exercise in the treatment protocol.

Treatment should be started at 30mg/kg by mouth twice daily and can be increased to 50mg/kg two or three times daily. It is advisable to have a strategy to stop medication once ID is controlled. Metformin can be added to decrease the absorption of glucose and, therefore, reduce the insulin peak, but it should be used as an adjunctive therapy rather than a curative one.

Levothyroxine can be used to increase weight loss when appropriate dieting has not achieved the required goal. In the author’s experience, some horses become agitated when on the medication and, therefore, it is not used. The prescribing veterinary surgeon should also be aware of the cascade and its implications when administering medications that are not licensed.

Testing for both PPID and especially EMS is complicated by the number of tests, and the different ways of interpreting the results. No one test is the “best” and, therefore, each should be chosen based on clinical knowledge and the case being presented.