20 Aug 2018

Sam Offord discusses the routine vaccination of an 11-year-old Thoroughbred cross novice event horse, in which an arrhythmia is detected on heart auscultation.

Your first visit of the day is for the routine vaccination of an 11-year-old Thoroughbred cross novice event horse; however, on heart auscultation, you detect an arrhythmia.

You note frequent beats arising sooner than you would expect for a normal rhythm. Auscultation on either side rules out audible murmurs and the rhythm is still present when the heart rate is increased by a brief trot. The remainder of the exam was unremarkable.

The owner is surprised when you report a dysrhythmia. The gelding has performed well throughout the season, and the owner has had no concerns about fitness or stamina when going cross-country. A previous examination that included cardiac auscultation roughly one year ago did not highlight any abnormalities.

How would you further investigate this abnormality and advise your client for the future competitive life of the horse?

An irregular heart rhythm not consistent with second-degree atrioventricular block should always be investigated, given some forms of dysrhythmia can have a significant impact on exercise tolerance and, occasionally, be associated with collapse.

For any abnormal rhythm, the most useful initial diagnostic test is a resting ECG. This can be performed in an ambulatory setting with relative ease using a traditional ECG with a paper trace or smartphone system1. An initial ambulatory ECG with a base-apex lead ruled out atrial fibrillation and showed multiple episodes similar to Figure 1.

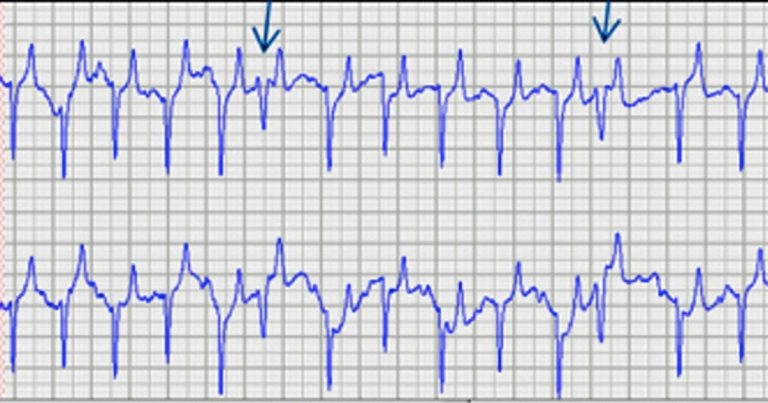

The fourth complex is premature, and the QRS complex is wider compared to the others, with a compensatory pause after. This is a ventricular premature depolarisation (VPD); the QRS complex is often wider with an occasional inverted T wave.

The monomorphic VPDs were visible throughout the 24-hour Holter ECG, with an average frequency of eight per minute – some of which were interpolated; that is, an interpolated complex falls between two normal QRS complexes and the underlying sinus rate is unaltered (Figure 2).

VPD can be seen infrequently in normal horses; however, the high frequency in this case is abnormal. The exact cause of VPDs is sometimes difficult to isolate; however, they derive from the ventricular myocardium. Any inflammation, necrosis or degeneration in the ventricular myocardium – also systemic endotoxaemia or electrolyte instabilities – are all potential instigating factors.

Echocardiography did not show structural abnormalities within the heart, as it is worth noting VPD can be seen in cases with severe mitral valve regurgitation. A serum sample for cardiac troponin was within normal limits.

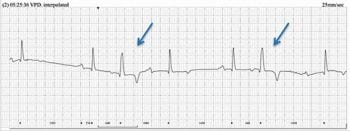

It is essential to establish if the cardiac rhythm is regular during exercise when evaluating ridden horses. Variety work should be performed consistent with the animal’s intended use. In this case, ECGs were recorded using a telemetry system2 during flatwork, jumping and fast work (Figure 3).

Treatment with oral anti-inflammatory therapy (prednisolone) was started for six weeks on a tapering dose, with no active exercise for four weeks. Following this, a re-examination, and resting and exercising ECGs, were performed over a range of different exertional regimes. These showed a reduced frequency of the VPD; however, intermittent premature complexes occurred during the cool-down period. No VPDs were present above 80bpm, with a maximal 186bpm achieved during the fast work.

Following the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine consensus statement3, it was decided to allow the horse to continue athletic activity, given the improvement in frequency of VPD with normal sinus rhythm at maximal heart rates.

A lack of structural cardiac abnormalities with no history of poor performance or collapse is also useful information when considering patients’ athletic futures. Risks – especially of sudden cardiac death – were discussed in detail with the owner. It was advised the horse has exercising ECG reviews annually, or sooner, should the owner report any performance issues.