22 Feb 2016

Romain Paillot and Adam Rash discuss equine influenza – one of the most contagious diseases of domestic and sports horses.

The AHT equine influenza surveillance team, supported by the Horserace Betting Levy Board (HBLB), confirmed 52 occurrences of equine influenza (EI) in the UK in 2014 and 2015. These are, of course, only snapshots of the problem, as many cases are not investigated or, if they are, samples may be taken too late in the infection to give a positive diagnosis.

Surveillance of any disease is vital for allowing optimal understanding of its spread, preventing its propagation locally, regionally or globally, and to investigate how the pathogen is evolving so effective vaccines can be produced.

As a World Organisation for Animal Health reference laboratory for EI, the AHT investigates how EI viruses evolve through studying outbreaks and viral isolates from around the world. Through enhanced awareness of risk, rapid and accurate diagnoses, and effective communication to inform appropriate actions to block opportunities for spread, the EI surveillance scheme aims for the successful control of EI globally.

To be successful in building the national and global map of virus outbreaks and strains, the surveillance scheme relies on the HBLB’s ongoing support, as well as samples sent in by practising veterinary surgeons who have registered with the AHT’s EI surveillance scheme.

EI can be diagnosed using either quantitative PCR (applied to nasopharyngeal swabs) to detect the presence of viral RNA or serology (paired clotted blood/serum) to detect rising antibody levels produced by the horses’ immune system following infection.

For a successful diagnosis to be given, swab samples should be taken as soon as possible, within two to three days of a horse showing clinical signs. Paired blood samples should be taken two to three weeks apart, with the first sample taken as early as possible.

Veterinary surgeons signed up to the surveillance scheme receive free testing kits and usually get test results back within 24 hours of submission of samples to the diagnostic laboratories.

Not only are vets able to advise on the correct diagnosis and administer the most appropriate and timely treatments for EI, they also provide essential viral samples to scientists to investigate changes in the virus that may allow it to escape immunity provided by vaccines – and, hence, spread more easily and widely among vaccinated and non-vaccinated horses.

AHT scientists monitor changes in the surface glycoproteins of the virus, haemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), by isolating live virus from submitted swabs. Viral genes that code for HA and NA are amplified and sequenced to compare the amino acid sequences against those from the vaccine strains and other viruses circulating in different parts of the world. This helps to identify any important changes between the vaccine strains and circulating

EI viruses.

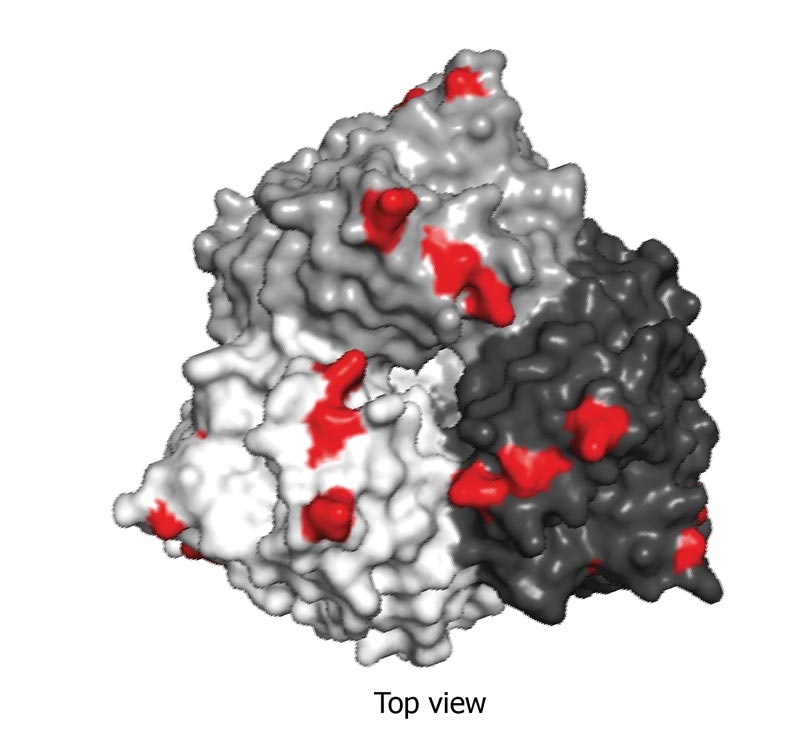

Using a protein crystallography program enables modelling of these amino acid changes on the surface of the HA protein (Figure 1). This illustrates both the extent of the changes and their location on the HA protein. In addition to this, antigenic studies are conducted on the new virus isolates to determine whether the vaccine strains are still likely to work against the latest circulating viral strains. Ultimately, this work leads to recommendations being put forward to vaccine manufacturers to produce the most up to date and effective vaccines for veterinary surgeons to then use in their clients’ horses.

Confirming a positive diagnosis for EI is necessary to the clinical situation to be best managed, so infectious transmission might be minimised and, where possible, steps taken to implement timely and geographically relevant booster vaccination initiatives. Scientists at the AHT would go further than diagnosis, though, by analysing the virus strain to achieve better future immunisation.

To maximise the chance of isolating live virus, samples should be collected within the first few days of the horse showing clinical signs, when virus shedding is at its highest level. This also improves the chances of a positive result being gained by quantitative PCR. It is, therefore, important awareness is high regarding the ongoing persistence of EI in the UK horse population.

In particular, the need to sample infected animals as quickly as possible after signs develop is important – among horse owners and their veterinary surgeons.

Owners and their vets working together are the most important part of any EI surveillance scheme as, without them, there would be no viral trail to follow.

Following a positive diagnosis of EI by AHT scientists, alerts are sent out advising vets and owners of it, including the UK county where the affected horses are.

Vaccination is one of the most effective methods of preventing EI, alongside effective surveillance, biosecurity and movement restriction. Several EI vaccines are available in the UK, but the overall principles apply to all of them.

EI vaccines are expected to significantly reduce the clinical signs of disease to improve overall welfare and recovery in the case of infection, and reduce the virus shedding to limit the risk of transmission and disease propagation. EI vaccines, however, rarely induce so-called sterilising immunity (that is, no infection, no disease, no viral shedding and no seroconversion).

Protection against EI induced by vaccination is mostly dependent on the production of circulating antibodies, which will recognise and neutralise the EI virus before it can infect the horse.

The following elements should be taken into consideration to optimise the effectiveness of EI vaccination and subsequent protection of the horse:

Protection induced by EI vaccination will fluctuate through time:

As for all vaccines, administration of an EI vaccine may induce some reactions, such as transient fever and local inflammation. These reactions, which indicate the horse’s immune system is responding to vaccination, are not unexpected, but should remain limited in terms of duration and severity. To improve the vaccine and its administration, adverse reactions should be reported to the VMD and the vaccine manufacturer.

Onset of minimal clinical signs is something a competition or sports horse owner should be aware and mindful of in his or her horse’s working schedule, so as not to jeopardise development of the immune system or performance.

The AHT immunology group is heavily involved in the evaluation, characterisation and/or registration of all EI vaccines licensed for sale in Europe. Several vaccine trials are conducted each year for all the major vaccine manufacturers to understand the immune responses produced following vaccination and the protection conferred. This work plays a pivotal role in the granting of product market authorisations and to evaluate the performances of EI vaccines.

The AHT immunology group, in collaboration with international partners, is also conducting overseas field studies to measure herd immunity to EI and to determine factors that undermine vaccine efficiency and coverage in the horse population (such as poor vaccine responders). Evidence of a prolonged and successful vaccination programme can be seen through that applied in the past 35 years by the UK’s racing industry. To protect the horses, the sport and the betting levy, it became mandatory in March 1981 for all horses competing on UK racecourses to be vaccinated against EI in accordance with new rules stipulated in the Jockey Club Rules of Racing.

The industry had already suffered the consequences of clinical EI spreading readily between training yards through horses mixing at racetracks, resulting in many horses becoming ill and meetings being cancelled due to EI outbreaks.

Introducing stricter regulations has succeeded in protecting the racehorse population from widespread outbreaks and the industry has not lost a day’s racing due to EI since the new rules were introduced. The HBLB has continued to invest in the prevention and understanding of EI by supporting the ongoing EI surveillance scheme conducted by scientists and vets at the AHT, who would very much welcome similar support from other equestrian disciplines and events that have undoubtedly greatly benefited from this work over the past three-and-a-half decades.