4 May 2022

Graham Duncanson BVSc, MSc(VetGP), DProf, FRCVS details what he has learned from his 50-plus year career regarding equine call outs to help fellow veterinarians.

Figure 1. A jump-starter is a useful backup for callouts.

I have never worked in an area where breeding mares are numerous. However, I would like to share my experience over a period of more than 50 years in mixed practice with call-outs to 363 foalings.

Potentially, a call to a mare foaling is the most urgent call you will receive in primary care equine ambulatory practice. It is likely in the UK to be at night and in winter, or early spring when temperatures are going to be sub-zero.

I think that it is helpful to have parked your vehicle in a frost-free situation. You do not want to spend 10 to 15 minutes clearing your windscreen. If that is not possible, remember to have a spray of de-icer in your glove compartment.

All car batteries have less power when cold. If you have access to a second vehicle then a set of good, thick jump leads is useful. If you do not have the use of a second vehicle then a jump-starter (Figure 1) is a useful backup.

Remember that it has a battery inside it that will have less power in the cold, so I would advise you to keep it inside in the warm. Bear in mind that these starters will only start small vehicles and certainly not big diesel engines. I have no experience of electric engine vehicles in sub-zero conditions.

I have a daughter in the profession. I worry about her having to turn out in the middle of the night. I gave her an old-fashioned long Maglite torch. This is useful for having a look under the bonnet in the dark. It is also useful to whack any drunk, over amorous male who takes any liberties. I am not being sexist; I am well aware that a strong woman is much better than a weak man. I keep a similar torch in my own van.

In total, 201 mares (55%) had already foaled before I had arrived. A further 79 mares (22%) were not even foaling. In these instances, it is very tempting not to get out of your warm car and to just drive away. However, I would advise that you do examine the mare for a twin, vulval tares and ventral oedema.

It is also prudent to spread out the fetal membranes (Figure 2). If you do not carry out what would be termed as a normal practice for a primary care equine veterinarian to perform, you may make the defence by the VDS harder if there are unforeseen consequences. Naturally there should be a charge for the OOH callout, as well as for the examination.

In the past 35 years I have run courses for owners who are inexperienced with foaling mares. Hopefully that has lessened the number of unnecessary call-outs. I am always happy to send any younger practitioners my PowerPoint presentation ([email protected]).

The take-home message from these figures is that, in my experience, only 23% of call-outs to foals require any real veterinary expertise.

In my case study only 83 (23%) out of 363 required some action by the veterinarian. Of these, 30 (8%) required gentle traction and a further 24 (7%) required simple repositioning of a single front leg. I hope I can reassure readers that only 29 cases out of a total of 363 callouts needed more sophisticated treatment.

I think it is important that you have a note of the telephone number of a local colleague either in your practice or a near neighbour that would be happy to render assistance, if you require it. Obviously, you should have to hand the emergency number of a referral practice.

Welfare must always be at the forefront in your mind. Older practitioners might consider that they should have a licensed firearm in a locked strong box in their car. Younger colleagues might consider an injection kit for euthanasia to be sufficient. Either way it would be prudent to have the telephone number of the nearest foaling bank to hand.

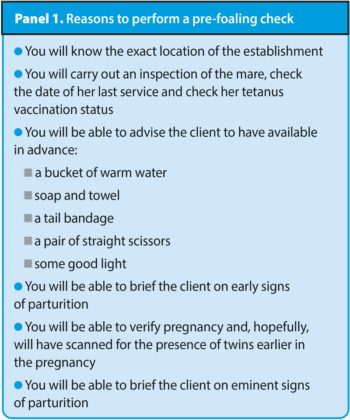

It is very helpful if you have performed a pre-foaling check for several reasons shown in Panel 1.

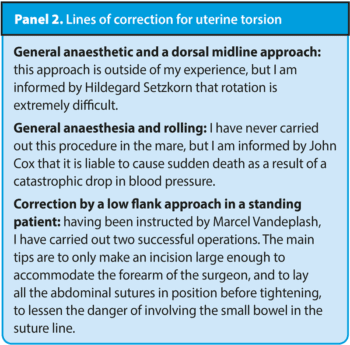

I think it is sensible to mention uterine torsion in this article, even though I am well aware that it normally occurs in the final trimester and not at foaling. The mare will show colic signs. The diagnosis should be confirmed by rectal examination, not by vaginal examination as in the cow. Various lines of correction have been advocated as shown in Panel 2.

I had 11 cases that I found on examination of the mare that the foal had its head back. These were very problematic. In five cases I was certain that the foal was dead. I failed to get the head up in these cases. After discussion with the owners, I carried out a fetotomy and removed the head, making the single cut as far caudal on the neck as possible.

The surgery was successful and the five mares survived. In six cases the foal was still alive. In three of these cases I managed to draw the head up and pulled a live foal. Sadly, two of these died within a few minutes. One foal survived.

In three further cases I took another approach. I discussed the problem with the owners. They realised that it would take more than two hours to get the mare to a referral practice for a caesarean section. The foal would then almost certainly be dead.

I gave them the option for me to give the mare a quick-acting general anaesthetic of rofimidine, followed by ketamine intravenously in the foaling box having made a deep bed. I would then as rapidly as possible draw the head up into the correct position and draw out the foal. In all three cases I was successful and we got a live foal. I had prepared a top-up dose of the two components of the anaesthetic, but these were never needed.

The foal in the dog sitting position may cause problems for the cattle practitioner as a diagnosis may escape them. Unlike in cows where relative fetal oversize is a very common problem, this is not seen in mares, where the mare decides the size of her foal regardless of the size of the stallion.

If a foal has a normal presentation and yet seems to be stuck, think dog-sitting foal. If the foal is alive, it is very handy to grasp the metacarpal bones firmly and push the foal as far back into the mare as possible. Then you work the forelegs vigorously and the foal will fall out.

Sadly, in one of my three cases the foal was dead. It was in a heavy mare. I managed to reach under the belly of the mare and slip two lambing ropes on the two hind fetlocks. I could then draw the hindlegs into extension. With some difficulty I drew the foal in a pear-shaped position.

I have had two breach presentations. These were both in heavy mares with unscanned twins. I managed to extend the hindlegs, probably as the foals were relatively small. In both cases one of the twins was saved.

I had one case where only the head of a dead foal was presented. I managed to remove the head very caudally down the neck. Then pushing on the body of the foal, I managed to pull up the two front legs and draw the foal. The mare survived.

I had a single case in a heavy mare where the front left foreleg of the foal was totally extended alongside of its body. The foal was dead, and I managed to draw it with traction to the leg and the head. The mare survived.

I have seen two rectal prolapses. These have been successfully replaced under local anaesthetic and secured with a purse-string suture, which was removed in 48 hours with no reoccurrence.

I have seen a single prolapse of the small intestine through the wall of the vagina. The foal was dead. The intestine was severely contaminated and the mare was recumbent. I shot the mare.

The condition, in my experience, is rare (one every 11 years of practice). My daughter was unlucky and had one within a month of qualifying, which had a successful outcome, except the owner only had £20 in his pocket and the practice failed to get the bill paid as he disappeared from the area.

Use of an epidural anaesthetic is beyond my experience, but it is recommended by many other authors.

I hope you have found these very unscientific notes helpful. I wish you every success (Figure 3). I hope you can take some solace from my experience that very few foaling call-outs result in drastic action.