16 Oct 2017

Jonathan Anderson looks at the anatomy of the distal phalanx and hoof before describing related foot conditions in the horse.

The distal phalanx develops from a single centre of ossification present at birth (Pollitt, 2016). It continues to enlarge and model until at least 18 months of age.

The palmar processes are not evident radiographically at birth, but ossify over 12 months. The dorsal surface of the bone is smooth, curved and radiographically opaque. The extensor processes on the dorsal aspect vary in shape and are usually bilaterally symmetrical.

The solar margin of the distal phalanx can vary in regularity, but is bilaterally symmetrical, as is the variably present V-shaped notch (crena marginis solearis) located on the midline of the dorsal aspect. This can be up to 1.5cm in depth and should not be mistaken for a pathological lesion (Pollitt, 2016).

Distinct collateral fossae are present on the dorsolateral and dorsomedial proximal aspect of the bone, which serve as the attachment sites for the respective collateral ligaments of the distal interphalangeal joint. The facies flexoria is the roughened solar surface of the most concave part of the distal phalanx, which serves as the region for the fibrocartilaginous insertion of the deep digital flexor tendon. The collateral cartilages extend proximally from both palmar processes and are variably ossified – depending on breed and age of the horse.

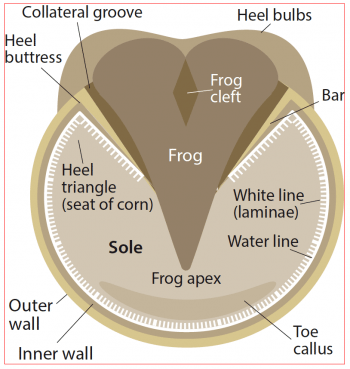

The hoof can be topographically divided into three parts: the wall, frog and sole (Figure 1; Pollitt, 2016). The bulk of the hoof wall is composed of stratum medium – a thick layer of tubular and intratubular epithelium produced by the coronary band epithelium (Figure 2). This is the primary weight-bearing surface of the wall.

Keratin is the main structural protein of the epidermis and forms the hoof wall. The tubular hoof wall is composed of hard keratin, is rich in disulphide bonds and has great strength. The solar surface of the hoof wall has a greater relative hydration, being softer than the hoof wall. The frog and white zone are rich in sulphydryl groups, but poor in disulphide bonds and have lower physical strength, but greater elasticity.

As the hoof wall grows, continual loss at the solar surface occurs. The hardness of the hoof wall is due to the disulphide bonds between and within its long chain fibrous molecules. Large numbers of small, circular holes cover the surface of the coronary groove, which extend distally into the body of the wall 4mm to 5mm – tapering to a point.

Continual regeneration of the hoof wall occurs at the coronary band where germinal cells produce keratinocytes that mature and continually add to the proximal hoof wall.

The highly vascular corium underlies the hoof wall and is a dense matrix of connective tissue containing arteries, veins and nerves. Other than the lamellar corium, all parts of the corium have papillae that fit tightly into the holes in the adjacent hoof. The lamella corium has dermal lamellae that interlock with the epidermal lamellae of the inner hoof wall and bars (Figure 2). The corium provides the hoof with nourishment and its connective tissue base adheres the basement membrane of the dermal-epidermal junction to the periosteal surface of the distal phalanx, suspending distal phalanx in the hoof capsule (Pollitt, 2016).

Unlike bone – a living tissue that remodels to become stronger along lines of stress (Wolff’s law) – the stratum medium of the hoof wall is non-living tissue anatomically constructed to resist stress in every direction and to never require remodelling. During normal locomotion, the stratum medium only experiences one-tenth of the compressive force required to cause its structural failure (Pollitt, 2016). However, excessive stresses – combined with poor hoof conformation, hostile environmental conditions and poor shoeing practices – can all result in increasing stress on this tissue, resulting in trauma and injury/disease, such as those outlined now in this article.

The simple foot abscess is the most common cause of acute onset severe lameness in the horse. Typically, presenting history is an acutely lame horse with a hot foot, a bounding pulse and possible swelling of the distal limb, which can occasionally extend up into the metacarpal/tarsal region. Usually, as a result of subsolar trauma – or a shallow, penetrative injury in which the elastic solar surface of the hoof is briefly compromised – the penetration quickly seals, trapping infection in the underlying dermal layers of the hoof wall (Figure 3).

While most subsolar abscesses will result in a focal area of pain, identified by the application of hoof testers, some are more deep-seated and less responsive to pressure. Curettage with sharp hoof knives of the affected region will reveal a focal black area in the white tissue, which, when followed, usually results in a larger pocket of exudate to manifest itself. If focal pressure and curettage yields only blood, the application of a poultice, magnesium sulphate in warm water, hydrogen peroxide and boric acid have all been used to help mature an abscess that has not yet matured.

Subsolar abscesses will track the path of least resistance and so can also continue up the white line – emanating at the coronary band. Again, they will usually burst out at the coronary band, resulting in a small separation of the hoof wall from the periople. Once the abscess is draining, application of dry poultice material and soaking of the foot in warm water with magnesium sulphate or hydrogen peroxide will usually result in resolution of the discharge and the associated lameness in a few days.

Separation of the white line will result in the potential for bacterial infection of the stratum medium of the hoof wall, leading to the development of cavities between the hoof wall and the laminae – resulting in white line disease. Cracks developing from dry conditions, or too much moisture, can both predispose to white line disease. Chronic laminitis, hoof cracks and poor quality hoof walls are all predispositions to develop the disease, and can result in varying severity of lameness, depending on the degree of drainage.

Other causes of lameness should be ruled out before attributing it to white line disease as this often is not a cause of lameness. Probing of the cavity is not usually painful and radiographic examination will reveal the extent of hoof wall separation (Figure 4). The white line is blocked out by a palmar digital nerve block at the level of the heel bulbs and, therefore, it can be confused with other diseases.

Therapy involves treating the existing condition and preventing future recurrence. This is best achieved in defects extending greater than 2cm proximally in the hoof wall by resection of the affected area using clippers or a motorised rotary tool, exposure of the necrotic laminae and application of drying agents and antibacterial agents daily to the affected region (Figure 5).

A 2.5% iodine solution, 10% formalin solution and thiomersal are applied topically. Once the surface is dry an acrylic patch can be used to fill the defect. The author prefers to layer the lamina with metronidazole powder prior to filing the defect. It is important the affected area is kept clean and dry, and, once the acrylic has been placed (Figure 6), the horse can usually return to full work.

Thrush is a fungal and often secondary bacterial infection of the lateral and central sulci of the frog of the horse’s foot (Figure 7). Fusobacterium necrophorum is particularly aggressive, invading and destroying the frog and sometimes exposing the deeper, more sensitive structures. Deep, narrow heel sulci, moist/wet conditions and poor foot care all predispose to thrush. Characterised by a malodorous black discharge in the affected region, variable pain is associated with it and it can result in swelling of the distal limb.

Avoided by good stable management, dry and clean bedding, and good hoof care, treatment is orientated around removal of all necrotic tissue, application of topical disinfectants (such as iodine solution) as well as drying agents (such as formalin), and shoeing to prevent mediolateral imbalance and long toe/low heel foot conformation. Treatment over the course of 7 to 14 days usually results in resolution. Formulated products, such as topical hoof hardener and copper sulphate, can be used on horses’ feet prone to thrush, but are not a substitute for good hoof care.

Canker is a proliferative pododermatitis of the frog that can extend to undermine the sole and heel bulbs. Often initially treated as thrush, as the problem persists it becomes distinctive as canker. It is more commonly seen in draft horses – possibly due to ease of hoof care management. It is differentiated from thrush by its foul, necrotic odour and the presence of granulation-like tissue that bleeds easily when manipulated (Figures 8 and 9). It tends to be proliferative and under-run the sole – destroying the normal definition of the frog and solar cornfield layer of tissue.

Treatment is difficult and takes patience on behalf of the owner, with recurrence common. The single most important part of treatment is debriding of the affected tissue, either cauterisation or sharp excision with cryotherapy, followed by application of a treatment plate to protect the foot and provide pressure against reformation of granulation tissue. Repeated debridement is usually necessary as deep clefts develop, making it hard to excise all abnormal tissue in the first instance.

Topical application of crushed-up metronidazole tablets and 10% benzoyl peroxide in acetone, as well as regular dressing changes, initially, usually allows the tissue to heal. Application of a caustic hoof paint (equal concentrations of phenol and iodine solution) can be initiated in the final stages of healing when cornification of the frog is complete, and for a week before removal of the treatment plate. Caustic agents used early are detrimental and worsen the course of the disease process.

Systemic antibiotics are not used by the author unless it is poor to respond and recurs. Penicillin or trimethoprim sulfonamides are suitable choices. If incorrectly treated, a 13-times increased incidence of recurrence exists (Oosterlinck et al, 2011). It can take weeks to months for horses to respond to treatment (Oosterlinck et al, 2011; Furst and Lischer, 2012) with multiple debridements sometimes necessary. The addition of prednisolone has been shown to approximately halve the duration of hospitalisation of affected horses (Oosterlinck et al, 2011).

By definition, pedal osteitis means inflammation of the distal phalanx. Both septic and non-septic pedal osteitis are described and, due to several discrete radiographic findings and associated clinical symptoms, the condition can be complex (Cauvin and Munroe, 1998). Septic pedal osteitis is an extremely painful condition that occurs usually because of solar penetrative injury and results in osseous resorption at the site of infection.

A chronic draining tract is located at the coronary band or solar surface of the foot associated with variable lameness. As the bone infection progresses, blood supply to the area is compromised, leading to an avascular necrosis and bone separation, with resultant sequestrum formation. It may take weeks before radiographically visible, although MRI can be used to determine potential sequestrae from areas of hyperintensity within the bone on fat-suppressed sequences.

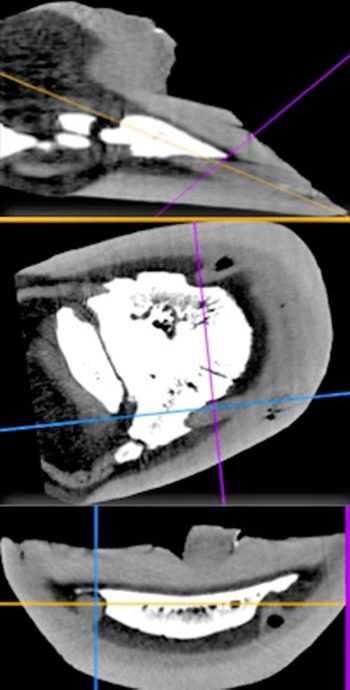

CT is also useful and can be used prior to debridement to provide more accurate landmarks for hoof wall resection and, thereby, minimise the amount of hoof wall removed. In addition, it enables accurate identification of other causes of bone resorption, such as keratoma lesions, which are readily identifiable on CT.

Changes in the bone most commonly include remodelling of the solar margin. Radiographically, the normal smooth outline of the distal phalanx is lost due to demineralisation and can progress to large areas of bone resorption, which can appear as widening of the vascular channels at the solar margin (Figure 10). Remodelling of the distal phalanx tip (lateral views) and new bone at the dorsal aspect, as a result of increased solar pressure (for example, in laminitis), are typical of pedal osteitis complex.

Elongation, remodelling and discrete radiolucent regions 2mm to 3mm in diameter in the palmar processes of distal phalanx represent part of the pedal osteitis complex, and are also likely due to concussive injury due to poor conformation and foot imbalance.

Treatment is aimed at aggressive debridement of affected bone through a sole resection, topical and systemic antibiotics, regional limb perfusions and placement of a treatment plate. Up to 25% of the distal phalanx can be removed with successful outcomes, as long as the affected portion of bone is removed and curretted back to healthy bone.

The use of medical grade sterile green bottle larvae is very useful in certain cases where margins of necrotic tissue are difficult to identify. They ingest 75mg of necrotic tissue per day, per larva; are both antibacterial and angiogenic; and have a five to seven-day life. Convalescence is protracted, although once the defect is covered with granulation tissue, soundness is often restored.

The use of a treatment plate can reduce the need for bandages and is very useful in post-debridement management. The author will also pack the defect in the hoof with metronidazole powder mixed with hydrogel prior to filling it with a resin-based acrylic when sufficient granulation tissue has sealed the defect.

Keratomas are uncommon, benign neoplasms of the equine hoof wall often associated with gradual onset of lameness, hoof wall deformation, recurrent subsolar abscessation and characteristic radiographic abnormalities (Boyes-Smith et al, 2006). Two types of keratoma morphologies are recognised. The typical discrete spherical keratoma is usually radiographically apparent by virtue of its adjacent osseous resorption of the distal phalanx, which is often smoothly marginated, semicircular and may have a sclerotic margin associated with it.

The other type of keratoma is more columnar in nature, with neoplastic tissue extending up and down the laminae, resulting in compression of the laminae and less distinct radiographic abnormalities (Anderson, 2013). Occasionally, varying degrees of calcification within the mass may allow further radiographic confirmation; however, most keratomas are not radiographically visible (Lloyd et al, 1988; Bosch et al, 2004). Although ultrasound has been helpful in the diagnosis of a keratoma, it is restricted to the soft tissue window provided by the coronary band.

A keratoma lesion is suspected by seeing osseous resorption of the distal phalanx; however, in many instances, no radiographic signs are visible. Both MRI and CT examination of the foot will definitively diagnose the presence of space-occupying masses, which can then be surgically resected. Histopathology of the mass is necessary for diagnostic confirmation, as other tumours, including squamous cell carcinoma (Berry et al, 1991), melanoma (Honnas et al, 1990) and glomus tumour (Brounts et al, 2008) have all been reported as neoplastic lesions within the equine digit.

In the author’s experience, a horse presenting with a chronic draining tract, or recurrent abscessation of the foot, warrants further radiographic investigation, often followed by CT examination (Figure 11). Even if radiographic evidence of bone resorption is only present in one part of the bone, more than one lesion can exist and advanced imaging then becomes invaluable in ensuring complete excision of all masses that may affect the foot (Figure 12).

Partial or total hoof wall resection is necessary to visualise the lesion and surgically resect it from the underlying tissues (Boyes-Smith et al, 2006). CT can be used to mark the margins of the lesion to ensure complete excision. The affected portion of distal phalanx is curetted, and the defect packed with a combination of a topical hydrogel with alginate and metronidazole powder. The bandage is replaced after 24 hours, and when a clot has formed the defect is covered by means of a hoof acrylic applied on top of a calcium alginate dressing placed on top of the clot. This is usually performed after 48 hours.

Once the defect is filled and a full bar shoe applied to the foot, the horse is normally stall-rested for two weeks prior to being returned to exercise if sound. The hoof wall will grow out and, if fully resected, recurrence of lesions is rare.