2 Sept 2019

Jamie Prutton reviews recent research carried out into this issue and provides a summary of available treatment protocols.

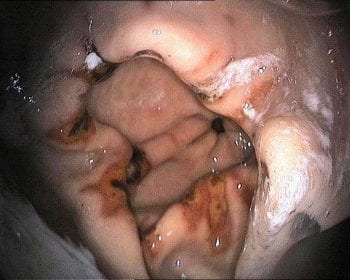

Equine squamous gastric disease. Grade two lesions on the lesser curvature.

Equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS) includes two distinct syndromes – equine glandular gastric disease (EGGD) and equine squamous gastric disease (ESGD).

Multiple articles have recently discussed the treatment and suspected aetiologies of these diseases; therefore, this article will address research over the past 12 to 24 months, as well as summarise the treatment protocols available.

When considering EGUS, it is now imperative to differentiate between both EGGD and ESGD to allow a complete understanding of the pathophysiology, treatment and prognosis in each individual case. This differentiation allows for tailored treatment protocols to be made.

Basic pathophysiology of ESGD indicates it is frequently an ulcerative or erosive condition affecting the squamous mucosa in the stomach. Acid damage has been shown to be associated with induction of ESGD; therefore, proton pump inhibitors will frequently result in resolution of the syndrome.

On the other hand, EGGD has a distinct pathophysiological process with no clear aetiology, and acid injury is not thought to be the inciting cause, although it likely contributes to the ongoing disease process and clinical signs.

Through this article, the author will assess the literature on risk factors, clinical signs, testing and treatment for both EGGD and ESGD, with a summary of most treatment modalities available to the veterinary surgeon.

The role of exercise in the formation of either EGGD or ESGD appears to be multifactorial.

Within a showjumping population, it was found exercising six days or more a week (compared to less frequently), current showing activity and increasing exercise intensity all increased the risk of either EGGD or ESGD. Competing at international level or eating beet pulp decreased the incidence of both EGGD and ESGD (Pedersen et al, 2018a).

Interestingly, when assessing polo horses, it was found decreased experience (number of years playing), increased exercise duration and NSAID administration were associated with ESGD grade one or higher, but decreasing weekly exercise was associated with ESGD grade two or higher – showing that classification of risk factors is complicated and each case should be treated individually (Banse et al, 2018).

The use of NSAIDs was frequently cited as a risk factor for the occurrence of gastric ulcers, although very little scientific literature confirmed this or discussed the suspected pathogenesis. A decrease in prostaglandin E2 following administration of phenylbutazone was researched as a possible pathogenesis – and although no effect could be seen on the prostaglandin E2 levels within the gastric mucosa, all horses that were administered phenylbutazone, rather than a placebo, had grade two or higher glandular disease after between three and seven days of treatment (Pedersen et al, 2018b).

Resolution of ulcers was not assessed, but the use of NSAIDs and their side effects should always be carefully considered.

The type of NSAID being used should also be considered, as more cyclooxygenase-2 selective medications (firocoxib) induced less severe ulceration than those that are less selective (phenylbutazone; Richardson et al, 2018).

One postulated theory is that crib biting is associated with gastric ulceration; whether the ulcers are the cause or effect is unclear. The physiology and pH within the stomach of horses that did and did not crib bite prior to euthanasia were assessed. No difference was found between the stomach physiology, pH or number of ulcers in their study (total of 21 stomachs in each group); therefore, an inherent link does not seem to exist between crib biting and EGUS (Daniels et al, 2019).

Although this is a relatively small list of risk factors, it highlights the ongoing research trying to address the unknown pathophysiology in both diseases.

An assumption exists that many clinical signs can be attributed to gastric ulcers – including decreased performance, girth pain, bruxism, discomfort when being groomed, changes in behaviour and changes in eating habits, to name a few.

Some studies have tried to assess these clinical signs more scientifically, with one showing only 40% of cases that were presented for girth aversion had gastric ulcers; however, the study had limited numbers (n=37) to draw serious conclusions from (Millares-Ramirez and Le Jeune, 2019). Others, though, have more conclusively associated poor performance with gastric ulceration.

Donkeys are a clinical conundrum generally – and gastric ulcers are no different, with 51.3% of a study population (n=39) having EGUS, whether this was located in the glandular or squamous mucosa, but presenting with no clinical signs. Whether these require treatment if they show no signs should be questioned, but 12.6% of the population had grade three or greater ulcers (Sgorbini et al, 2018).

At present, the only appropriate way to test for gastric ulcers is via gastroscopy. With that in mind, a large amount of research exists into other tests that would negate the requirement for gastroscopy.

Hair cortisol levels can act as a marker of medium-term to long-term stress and, therefore, may show a correlation with ESGD. Research into resting cortisol showed it was negatively correlated with the presence of ESGD; therefore, further investigation would be required prior to the test becoming commercially available (Prinsloo et al, 2019).

Another group assessed the use of an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation, with assessment of the cortisol production in saliva as a marker for ESGD and EGGD. Although they found a correlation between a 60-minute post-ACTH administration sample and the presence of EGGD, the data was not conclusive; therefore, at this time this test does not show promise as a diagnostic modality (Sauer et al, 2018).

Gastric ulceration is an inflammatory process and serum amyloid A (SAA) is a sensitive marker of inflammation. It was postulated, therefore, whether a correlation could exist between SAA and gastric ulceration. No correlation was found, with only a small number (n=10) of 114 gastroscopies having elevated SAA (Spanton et al, 2019a). Therefore, this test cannot be recommended as part of a screening tool.

Proteomics is a tool for screening protein markers within serum, but does not confirm the function of those proteins found. Theoretically, if a difference in serum proteins can be found, this could be used as a screening tool. Tesena et al (2019) found 10 proteins that were expressed in varying levels, depending on the presence of gastric ulceration and its severity. This technique may, in future, allow for some of these proteins to be used to diagnose ESGD and remains an open area of research.

Gastroscopy, therefore, remains the gold standard – and although it is thought of as a benign test, multiple papers have shown clinical side effects of gastroscopy.

The most recent study showed a prevalence rate of post-gastroscopy colic of 2.9%, with one case (0.2%) requiring exploratory laparotomy. The majority of the colic episodes appeared to be associated with gastric impaction and resolved with only medical intervention (Spanton et al, 2019b).

Although not a high-risk procedure, clinicians should be aware post-gastroscopy colic can occur in a limited number of cases, although the author, thankfully, has not seen this.

A plethora of other options are available to owners – mostly in the form of nutraceuticals, each with very little scientific evidence of their efficacy. Some research has been undertaken looking into use of nutraceuticals and feed supplements, with most results showing at best a mild improvement. However, in the author’s opinion, many of the studies are of questionable scientific merit, with small numbers of horses included; therefore, their use must be judicious and as an adjunctive therapy, rather than monotherapy.

Feed and modern management play a critical role in the formation of EGUS, with an increased risk for ulcers seen with high-starch and sugar-rich diets alongside intermittent grazing and foraging. This poor diet leads to a poorly buffered, acidic gastric environment subsequently increasing the pressure for EGUS.

One study has evaluated the response to omeprazole within two groups of horses – one with a continued high-starch/sugar diet in race training, the other with a reduced-starch/sugar diet alongside continued race training. Both groups were given omeprazole for four weeks only. In both treatment protocols, significant improvement occurred in the severe ulcers between initial scope and the second scope four weeks later. When a further scope was performed 10 weeks after the initiation of treatment, the horses maintained on a high-starch/sugar diet showed recrudescence of ulcers to the same level as prior to treatment, while those on the reduced-sugar/starch diet had maintained the improvement (Luthersson et al, 2019).

This study demonstrated the importance of a holistic approach to gastric ulceration, and how diet plays a significant role in the treatment and prevention of ongoing disease.

The search for alternative therapies will continue, with aloe vera recently investigated. It was found that when given at a dose of 17.6mg/kg twice a day – compared with omeprazole at 4mg/kg once a day – for the treatment of grade two and higher ulcers, aloe vera was inferior. A number of horses in the aloe vera group did have an improvement in their gastric ulcers, but no control group was included to compare whether this was due to the aloe vera or normal changes (Bush et al, 2018). Therefore, its use as a sole agent cannot be recommended, but whether it may help as an adjunctive therapy requires further investigation.

Many horses are placed prophylactically on treatment for ulcers – particularly in the racing industry. With ulcers affecting maximal oxygen uptake significantly, the prevention of ulcers would be highly beneficial to racing outcomes.

A meta-analysis was performed that looked at seven studies – with a total of 566 horses – and found prophylactic omeprazole treatment did reduce the occurrence of gastric ulceration when compared to sham treatment. Overall, the rate of occurrence of gastric ulcers in the treated group was 23.4%, compared to the sham group of 77.2%. The doses used in these studies was either 1mg/kg or 2mg/kg, as the studies evaluating the 0.5mg/kg and 4mg/kg doses were small and not appropriate for analysis. Therefore, prophylactic use can reduce the occurrence of gastric ulceration in racehorses (Mason et al, 2019).

It should be noted the use of omeprazole in racehorses must comply with the appropriate authorities and this should be checked prior to administration.

Misoprostol (5µg/kg twice daily) has been shown equally effective as a monotherapy when compared to combined omeprazole (4mg/kg once daily) and sucralfate (12mg/kg twice daily) for the treatment of EGGD (Varley et al, 2019). The use of misoprostol (and any other medication not licensed for horses) should only be done so under the appropriate cascade route, which is discussed in more detail later in this article. The human health implications of misoprostol must also be considered when prescribing this medication.

Injectable omeprazole has become a frequently used product for glandular ulcers and has been shown to have a success rate of 75% (Sykes et al, 2017). The study assessing the injectable omeprazole contained only 12 horses – and when compared with the study assessing the combination of omeprazole and sucralfate (n=204), the success rate showed little difference (Hepburn and Proudman, 2014).

The combination therapy remains the European College of Equine Internal Medicine (ECEIM) consensus statement primary treatment protocol. As with sucralfate, this medication is a “special” preparation; therefore, its use must comply with the cascade.

Evidence has emerged that the long-acting injectable omeprazole product contains testosterone, a banned product under most equine governing bodies. Given these findings, the use of the long-lasting injectable omeprazole is prohibited in horses competing under British Horseracing Authority rules – and its use must be carefully considered and discussed in horses competing under any governing body, as testosterone is a banned substance under Fédération Equestre Internationale rules, as well. Its use in non-competing animals can continue, although care should be taken as this recent work does show contamination when the licensed products showed no such problems. A news article about this appeared in the 26 August issue of Veterinary Times (VT49.34).

A definitive protocol for all patients is impossible to dictate, as clinician-driven advice regarding diet and management will play a pivotal role in the plan created.

Firstly, EGGD and ESGD must be separated and considered as different disease entities. The latter’s treatment revolves around the use of omeprazole as a monotherapy in the first instance. With the oral preparation being licensed and its excellent success rate, limited requirement exists to cascade to other medications.

If failure of treatment arises, cascading can occur with the addition of sucralfate, misoprostol, antibiotics or injectable omeprazole. Antibiotics should only be considered if a prolonged treatment course has taken place with no resolution in the clinical signs – ideally, it should be based on culture and sensitivity from a biopsy.

Treatment of EGGD is moderately complicated due to the lack of complete understanding around the aetiology and pathogenesis. Treatment options include:

The cascade plays a pivotal role in the safe and, ideally, evidence-based administration of medications in the veterinary industry. If a licensed product exists for the condition, this must be used. If a suitable product does not exist then veterinary surgeons can follow the cascade and administer medications based on the following algorithm.

When a non-licensed product is used, a consent form should be signed by the owner and informed consent given prior to administration. It should be noted inappropriate deviation from the cascade is a criminal offence.

If no licensed product exists, the following steps – in order of suitability – must be followed:

The veterinary surgeon in charge of the case must feel he or she has followed the cascade appropriately and should take into consideration the licensing for the oral omeprazole products, which states its use is for “treatment and prevention of gastric ulcers”.

Research continues at a high rate in all fields of gastric ulceration, with particular attention being paid to the treatment of EGGD and its possible pathogenesis. It is likely, within a short period, further evidence will emerge – allowing a more tailored approach to treatment.