21 Aug 2023

Zoë Gratwick BVSc, MSc, MMedVet, DipECEIM, MRCVS covers the common (and uncommon) causes for fever in this species, and how to test for and treat it.

Image: © Dirk70 / Adobe Stock

In the UK, most horses demonstrating pyrexia have a viral or bacterial infection. If localising signs are absent, it is more likely the horse has a common disease without the common clinical signs than an uncommon disease being present.

Other possible causes of pyrexia include parasitic or fungal infections, neoplasia, tissue damage associated with toxicity and immune-mediated disease. Hyperthermia may also be worth consideration in some cases. In the UK, a significant percentage of pyrexic horses are affected by contagious respiratory disease, colitis or peritonitis.

The clinical history can often provide valuable insights. In particular, questions should aim to identify clinical signs and risk factors associated with colitis and contagious respiratory disease.

Horses with colitis do not always have diarrhoea at the time of presentation. Furthermore, contagious respiratory disease should not be excluded by a lack of movement on or off a property: influenza can travel on the wind and disease due to equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1) or 4 (EHV-4) can be the result of recrudescence of a latent infection.

Especially if respiratory signs are present, questions to help determine whether bacterial pneumonia could be present are important. Bacterial pleuropneumonia in adult horses is typically associated with a risk factor. Risk factors for bacterial pneumonia include:

In addition to less specific signs of respiratory disease, clinical findings that increase the suspicion of bacterial pneumonia include congested mucous membranes, laminitis or brown nasal discharge. However, these signs are not always present.

Especially in cases where respiratory disease or colitis are less likely, more comprehensive questions about general health and performance can increase the suspicion of a less common reason for pyrexia.

Risk factors for colitis include:

A comprehensive clinical examination should be performed, and it may narrow down the list of differential diagnoses. If the type of disease present remains unclear, then assessment for respiratory pathogens, haematology, serum biochemistry and peritoneal fluid analysis may be useful next steps. If the findings are within normal limits and clinical signs persist, rectal palpation, and ultrasonographic assessment of the thorax and abdomen, may be advisable.

The most practical way to offer preliminary assessment for contagious respiratory pathogens is to submit a nasopharyngeal swab for combined PCR testing for equine influenza virus, Streptococcus equi subspecies equi, Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus, EHV-1 and EHV-4.

Concurrently, serum can be collected and if the PCR results are negative, paired serology for EHV-1, EHV-4 and strangles could be performed. If any suspicion of EHV-1 infection exists and the PCR result is negative, paired serology should always be performed.

For the aforementioned infections, negative PCR results from single samples do not always equate to an absence of infection. Infected animals are not always shedding into the nasopharynx at the time of sampling. Furthermore, other reasons for false negative test results can exist.

Equine rhinitis A virus, equine rhinitis B virus and, equine coronavirus can also cause pyrexia and respiratory signs. These infections are contagious. Shedding can be detected by nasopharyngeal swab PCR.

The clinical picture seen with equine coronavirus is variable. Some horses are asymptomatic carriers while some may demonstrate pyrexia, anorexia, lethargy, diarrhoea or respiratory signs.

Haematology and biochemistry may be useful if the cause of the signs is unclear.

An increase in serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) concentration or hypoalbuminaemia could potentially reflect intestinal disease (other possibilities exist). Increases in serum ALP, aspartate transaminase, gamma-glutamyl transferase or glutamate dehydrogenase concentrations may reflect a hepatopathy.

Combined increases in serum urea and creatinine concentrations usually reflect kidney injury. This could reflect a primary pathology, such as pyelonephritis, or could be secondary to an underlying disease process. An example would be when hypovolaemia or endotoxaemia has been present due to colitis.

It is advised that clinically relevant inflammation should not be excluded by an absence of an indication in the haematology/biochemistry results. If the horse is pyrexic, it is highly likely that inflammation is present. Hyperthermia could be a possibility – particularly in obese native breed animals during the summer – but this is significantly less common than pyrexia.

Peritoneal fluid analysis will confirm whether peritonitis is present. Increases in total white cell count and total protein concentrations indicate the presence of intra-abdominal inflammation, which could be primary or secondary. If inflammation is present, or if this is unclear, cytological assessment of stained smears may offer both confirmation and, sometimes, insight as to the underlying cause.

If peritoneal inflammation is present, bacterial culture of a peritoneal fluid sample is advised (ideally collected into a transport swab).

If a suspicion of intestinal disease exists, then faecal examination, faecal pathogen testing, rectal palpation and abdominal ultrasonography could be useful.

As mentioned previously, not all cases of colitis have diarrhoea.

For faecal examination:

In adult horses, bacterial colitis is relatively uncommon. When present, it is principally due to Salmonella species, Clostridium perfringens or Clostridium difficile.

Testing for Salmonella species can be done by faecal culture or qPCR. Ideally, three to five separate faecal cultures should be performed. Assessment of a single sample could lead to a missed diagnosis.

An enriched qPCR is a useful diagnostic test. However, a non-enriched qPCR carries a very low diagnostic sensitivity. Not all labs may use a validated enrichment technique and such results are much less useful if negative.

A faecal multi-toxin ELISA for C perfringens is widely available. Often, “organism antigen” is included in an ELISA report. Sometimes, this enables identification of the organism in the absence of toxin detection.

This can mean a variety of things: firstly, toxins may have denatured prior to testing, leading to false negative toxin results. It is recommended that samples are sent chilled to be processed within 24 hours, minimising the likelihood of toxin denaturation.

Alternatively, a non-tested toxin could be present, for example, netF. Bacteria could also be present in the faeces without producing toxins. Selective faecal culture is possible, but challenging and not widely commercially available.

A faecal ELISA is also available for the detection of C difficile toxins A and B, as well as a PCR for A and B toxin-producing genes.

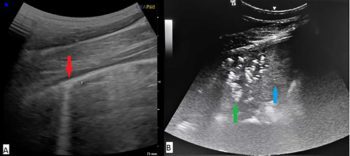

Pulmonary ultrasonography will usually provide valuable information regarding the possibility of bacterial pneumonia (Figure 1). It also has the benefit of being non-invasive.

Pleural surface irregularities, lung parenchymal consolidation and pleural effusion may be seen. Tracheal wash and bronchoalveolar lavage cytology will often provide useful information, and if bacterial pneumonia is present, tracheal aspirate cultures will usually enable targeted therapy.

The incidence of clinical tick-borne infections in UK horses is unknown, but relevant infections with Anaplasma phagocytophilum and Borrelia burgdorferi do occur.

Horses infected with A phagocytophilum may develop clinical signs such as pyrexia, lethargy, inappetence, limb oedema and, occasionally, neurological signs. Anaemia, thrombocytopenia and leukopenia are usually present.

In most cases, parasite morulae are detectable within granulocytes (usually neutrophils) upon blood smear examination.

Lyme disease due to B burgdorferi has a highly variable presentation. Pyrexia, neurological signs, uveitis, muscle wasting or pain, abortion and arthritis have all been reported.

Prognosis for a bacterial infection is usually best when the site and type of infection are able to be identified. This way, a targeted approach can be employed.

However, when bacterial infection is suspected, but the location cannot be identified, aseptic collection of multiple blood cultures will sometimes enable identification of bacteraemia, facilitating targeted antimicrobial treatment if indicated. Cultures are thought most likely to yield positive results if sampling is performed during a period of pyrexia.

Many other uncommon causes of equine pyrexia exist. If none of the aforementioned diseases are suspected or diagnosed, other less common diseases warrant consideration.

Where a suspicion of contagious disease exists, a horse should be isolated, and movement both on and off the premises should be restricted.

The majority of pyrexic horses will benefit from NSAID administration. This offers the benefits of reducing pyrexia, reducing inflammation and offering analgesia.

However, in some instances NSAIDs are contraindicated, creating a management challenge. NSAIDs are contraindicated if NSAID-associated colitis is suspected.

Furthermore, in patients with severe hypovolaemia or suspected renal disease, NSAIDs pose a risk to renal health.

Depending on the nature of the disease, in these patients a role may exist for paracetamol in controlling pyrexia and providing analgesia. While corticosteroids are not associated with analgesic effect, when inflammation is the driver for discomfort, in some cases, a role may exist for their short-term administration.

The vast majority of strangles cases will not require systemic antimicrobial therapy. However, instances occur when this may be beneficial – for example, for cases in respiratory distress.

Supportive care may include NSAID therapy, lancing and drainage of abscesses, tetanus prophylaxis and, sometimes, hydration and nutritional support.

Cases with guttural pouch empyema will likely benefit from guttural pouch lavage. This helps to minimise chondroid formation and potentially expedites recovery from bacterial carriage. Intrathecal instillation of penicillin gel is commonly used in an attempt to expedite eradication of bacteria from the guttural pouches.

Many immunocompetent adult horses affected by primary contagious S equi zooepidemicus infection will not require antimicrobial therapy. Supportive care and monitoring is often adequate.

However, if a case fails to improve despite supportive care, then antimicrobial therapy is indicated. Occasionally, for severely affected cases such as those demonstrating respiratory distress, severe lethargy or pyrexia that does not respond to NSAIDs, early antimicrobial therapy may be justified (in young foals, antimicrobial therapy is indicated).

In those cases requiring antimicrobial therapy, infections can be stubborn to treat and they often recur following short courses of treatment.

Antimicrobial therapy is an appropriate first-line approach in cases with secondary bacterial pneumonia or pleuropneumonia (including those where S equi zooepidemicus is isolated).

In these cases, prompt antimicrobial therapy is beneficial.

In severe cases, aggressive hospital-based management is often required. This may include pleural fluid drainage, local fibrinolytic therapy or surgical debridement.

At first presentation, often the exact reason for the combination of pyrexia and respiratory signs is unknown. In such cases, the following guidelines could be considered:

Key considerations for colitis include:

Encysted cyathostomins are typically treated with five days of fenbendazole or a single dose of moxidectin. Fenbendazole resistance is thought to be widespread.

In cases with acute colitis, initiation of supportive care alongside direct treatment is often beneficial, as intestinal inflammation, diarrhoea and, potentially, both cardiovascular status and foot health may deteriorate following treatment.

In clinical cases of suspected cyathostominosis, reliance on a serological ELISA is not advised. Concurrent corticosteroid administration may be advisable, unless specifically contraindicated.

Antimicrobials have the potential to adversely affect recovery in colitis cases. They should not be a routine component of therapy.

However, cases exist where their use is likely to be beneficial.

If C perfringens or C difficile are identified, and the horse is systemically compromised, then metronidazole therapy could be indicated. If the horse is severely compromised and another reason for colitis is not evident, antimicrobial therapy might be considered prior to faecal results becoming available.

Antibiotics are not generally recommended in acute cases of Salmonella species-associated colitis. However, they may be required in chronic cases where recovery from clinical signs and cessation of shedding have been unsuccessful. In these cases, it is important to also consider why recovery has been inadequate and whether additional factors require attention.

Antibiotic choice should be based on an antibiogram to facilitate effective targeted treatment.

Di-tri-octahedral smectite binds toxins, bacteria, viruses and free radicals. Experimental evidence suggests it is useful in the treatment of equine colitis and in helping to prevent diarrhoea in at risk patients.

Some medications bind to this compound, so this should be considered when medication timings are being decided.

Experimental evidence suggests metronidazole does not bind to this clay.

Probiotics are suggested to modulate the immune system, produce antimicrobial compounds, inactivate bacterial toxins and increase colonisation resistance.

Only weak evidence exists to suggest that probiotics are useful in adult equine intestinal disease, although a role may exist for them to play.

Whether probiotic use is safe in adult horses is unknown, but adverse effects have not been reported.

Some (limited) evidence exists that faecal microbial transplantation (transfaunation) may be helpful in cases with acute colitis. The main potential risk associated with transfaunation is the transmission of infectious disease from the donor to the recipient. Donors should be clinically healthy.

As a minimum, faecal testing should include a faecal Salmonella species culture/enriched qPCR and a faecal egg count. An optimal protocol is unestablished, but typically, 2L of final product per 500kg horse is given per administration via nasogastric tube.

Misoprostol therapy may be beneficial – especially in cases with NSAID toxicity. This prostaglandin analogue is thought to increase intestinal blood flow and decrease neutrophilic inflammation.

Misoprostol is contraindicated in pregnancy and must not to be handled by pregnant women.

The majority of horses with pyrexia have a viral or bacterial infection. The clinical history and physical examination will often point towards the reason.

However, in cases where they do not, then contagious respiratory disease, colitis and peritonitis are worth particular consideration.

PCR assessment for respiratory pathogens, haematology, serum biochemistry and peritoneal fluid analysis are usually useful next steps.