10 Jun 2019

Nicola Menzies-Gow discusses the signalment and clinical signs of this condition, and challenges presented by further diagnostic testing.

Figure 1. An 18-year-old Shetland pony gelding with generalised hypertrichosis and chronic laminitis consistent with pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction.

Pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disease of the horse.

Diagnosis of PPID is based on the signalment, clinical signs and further diagnostic test results. The condition is seen in older animals – the average age of affected animals is 18 to 23 years; the youngest confirmed case was 7 years old. Therefore, the age of the animal should be considered before further diagnostic testing is undertaken.

Some clinical signs associated with PPID are often mistaken by owners as changes associated with ageing. Therefore, owners recognising these signs may not regard them as important enough to seek veterinary advice – and animals with PPID may go undetected. However, owners are better at detecting hypertrichosis compared to a veterinary clinical examination, so a detailed history and thorough clinical examination are important.

No ideal further diagnostic test exists for equine PPID; however, plasma basal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) concentrations and the ACTH response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) are thought to be the most appropriate tests available.

Two areas relating to plasma ACTH concentrations potentially create difficulties when using this test to make a diagnosis of equine PPID – namely, the cut-off value and the assay used to measure ACTH concentration. The sensitivity and specificity of the test are greatest in the autumn, when seasonally adjusted cut-off values are employed. Some authors suggest, rather than a specific cut-off, a grey zone should exist of ACTH concentrations – and results falling within these zones should be considered as equivocal, requiring testing to be repeated or a TRH stimulation test to be performed.

The ACTH response to TRH is affected by season and probably best avoided in the autumn, if possible. A subset of animals with PPID also have insulin dysregulation (ID), and ID appears to be associated with an increased risk of laminitis and a worse prognosis. ID can manifest as hyperinsulinaemia, an excessive insulin response to oral carbohydrate and tissue insulin resistance. Tests are available to investigate each of these.

Equine pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (PPID) is a slowly progressive neurodegenerative disease with loss of dopaminergic (inhibitory) input to the melanotropes of the pituitary pars intermedia, which appears to be associated with localised oxidative stress and abnormal protein (α-synuclein) accumulation. However, the exact cause remains unknown.

The consequent dysfunction of this region results in hyperplasia of this area of the gland and overproduction of pars intermedia-derived hormones. Eventually, the area undergoes adenomatous change.

Diagnosis of PPID is based on the signalment, clinical signs and further diagnostic test results.

The condition is seen in older animals – the average age in retrospective case series ranges from 18 to 23 years1-4.

No breed or sex predilection exists, but ponies are more frequently affected than horses in some studies2-4. In one survey, 21% of horses older than 15 years had endocrine changes consistent with PPID5. In a separate study, clinical signs consistent with PPID were documented in nearly 40% of horses older than 30 years6.

However, it should be noted the disease has been recognised in animals younger than this, with the youngest reported case being in a seven-year-old animal7. Therefore, the age of the animal – and the likelihood of PPID being a true diagnosis – should be considered before further diagnostic testing is undertaken.

Clinical signs associated with PPID can be roughly divided into those seen early in the disease and those associated with advanced disease.

Early signs include decreased athletic performance, change in attitude/lethargy, delayed haircoat shedding, regional hypertrichosis, change in body conformation, regional adiposity and laminitis. Late signs include lethargy, generalised hypertrichosis (Figure 1), skeletal muscle atrophy, hyperhidrosis, polyuria/polydipsia, recurrent infections, infertility and laminitis.

Some of the clinical signs associated with PPID are often mistaken by owners as changes associated with ageing. Therefore, owners recognising these signs may not regard them as important enough to seek veterinary advice and animals with PPID may go undetected5.

However, it has also been shown owners are better at detecting hypertrichosis compared to a veterinary clinical examination5. As a result, the historical information provided by the owner is important, as well as a detailed clinical examination, to detect the clinical signs associated with PPID.

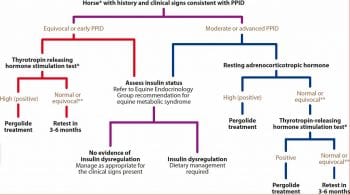

No ideal further diagnostic test exists for equine PPID; however, plasma basal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) concentrations and the ACTH response to thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) are thought to be the most appropriate tests available (Figure 2).

It has been shown ACTH concentrations are significantly increased in animals with acute laminitis, as well as in animals with both acute and chronic disease8. Therefore, if possible, further diagnostic testing should be delayed until any laminitis or concurrent disease has resolved.

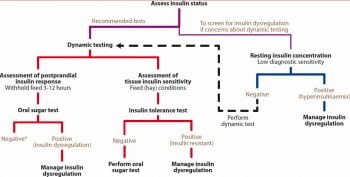

Appropriate tests for ID include measurement of basal serum insulin concentration, an oral sugar test (OST) or oral glucose test (OGT), and the insulin response test (IRT).

Two areas relating to plasma ACTH concentrations potentially create difficulties when using this test to make a diagnosis of equine PPID – namely, the cut-off value and the assay used to measure ACTH concentration.

Plasma ACTH concentrations vary with season – with a seasonal rise spanning from July to November in the UK, corresponding to the change in day length.

Throughout the year, plasma ACTH concentrations are greater in animals with PPID, compared to normal animals, and this autumn rise is greater in animals with PPID compared to normal horses12. Therefore, autumn is the best time of year to test for PPID.

However, if an animal has clinical signs suggestive of PPID and is presented for evaluation in the non-autumn period, it is prudent not to wait to undertake further diagnostic tests. Instead, it is essential a seasonally adjusted reference range is used when interpreting ACTH concentrations.

The cut-off value recommended consistent with a diagnosis of PPID varies between publications12-16. Suggestions for the non-autumn period range between 27pg/ml and 50pg/ml, while suggestions for the autumn period range between 47pg/ml and 100pg/ml.

The sensitivity (correctly detects a positive result) and specificity (correctly detects a negative result) of these cut-off values is only reported in a subset of these publications.

In those publications where season is not adjusted for, the sensitivity and specificity values range from 65% to 100%, and 78% to 100%, respectively3,14,15,17,18. The lowest values in these ranges equate to an incorrect test result in either the positive or negative direction, occurring in approximately 3 of every 10 tests performed.

False positives occur due to physiological increases in ACTH concentration, such as severe pain, strenuous exercise and moderate-to-severe illness19. False negatives are thought to occur due to poor ability of the test to detect early disease.

The sensitivity and specificity of the test do not appear to be improved by measuring ACTH concentrations in paired samples14. However, measuring ACTH concentrations in autumn using a seasonally adjusted cut-off value does appear to result in a significant improvement in these values. In the single publication that determined the sensitivity and specificity of autumn (77.4pg/ml) and non-autumn (29.7pg/ml) cut-offs, sensitivity and specificity values of 80% and 83%, and 100% and 95%, respectively, were reported13.

It should be noted the studies used to determine these values vary with respect to the criteria used to define an animal as PPID-positive, while the majority of studies required the presence of hypertrichosis to classify an animal as positive for PPID. Therefore, although it would appear it is best to measure plasma ACTH concentrations in autumn, the sensitivity and specificity of plasma ACTH concentration for the diagnosis of PPID animals without hypertrichosis, regardless of the time of year, is less certain.

As well as the autumn rise, it would appear a nadir in plasma ACTH concentration occurs in April20, so an alternative diagnostic cut-off may also be required for the month of April.

The size of the autumn rise in plasma ACTH concentration appears to vary with horse-related factors, including breed, sex and coat colour21. For example, greater rises occurred in Shetlands, mares and grey-coloured animals. Consequently, the cut-off values recommended for a diagnosis of PPID may additionally need to vary according to horse-related factors. All of these variables require further investigation.

It has been suggested by some authors, rather than a specific cut-off, a grey zone should exist of ACTH concentrations between 19pg/ml and 40pg/ml22, or 30pg/ml and 50pg/ml (Equine Endocrinology Group), in the non-autumn months; and between 50pg/ml and 100pg/ml (Equine Endocrinology Group) in the autumn.

Results falling in these zones should be considered as equivocal, requiring repeat testing or a TRH stimulation test to be performed. However, the sensitivity and specificity of these grey zones has yet to be determined.

Interpretation of ACTH concentrations within such a grey zone should be done in light of the clinical signs and the results of other further diagnostic tests undertaken. For example, if an overweight animal has a non-autumn ACTH concentration within the grey zone; recurrent laminitis, but no other clinical signs; evidence of ID; and a low plasma adiponectin concentration; this would be more suggestive of equine metabolic syndrome. Early PPID may be present and it would be prudent to either perform a TRH stimulation test or repeat the basal ACTH concentration measurement in the autumn.

In contrast, if an underweight animal has a non-autumn ACTH concentration within the grey zone, recurrent laminitis, hypertrichosis, polyuria and polydipsia, and no evidence of ID, this would be suggestive of PPID. Either a TRH stimulation test could be performed or trial therapy with pergolide recommended.

More than one method has been validated for the measurement of ACTH concentration in equine plasma samples. The method used by most commercial laboratories in the UK is the chemiluminescence (CL) method. Other validated methods available include an immunofluorescence (IF) method.

It has been reported the results obtained from the CL and IF methods do not agree, with results using the IF methods being lower than those obtained using the CL method (median difference 29.9pg/ml)23. As a result, cut-off values recommended for the diagnosis of PPID should be specific to the assay. Additionally, it would appear ACTH degradation products – such as corticotropin-like intermedia peptide (CLIP) – cross-react with the CL assay or interfere with the IF assay23.

Therefore, the CL method may be measuring other pars intermedia-derived proopiomelanocortin (POMC) products, as well as ACTH in equine plasma. Whether this cross-reaction is useful when making a diagnosis of equine PPID has yet to be determined.

TRH is a physiological release factor for the equine pituitary, so its administration stimulates release of the normal hormone products from the pars intermedia. The ACTH response to TRH is measured – a dose of 0.5mg, 1mg or 2mg of TRH produces ACTH responses that are not significantly different24,25.

The sensitivity and specificity of the test in animals with two or more clinical signs consistent with PPID – using a cut-off value of 36pg/ml after 30 minutes – in three studies were 94% and 78%, respectively17; 88% and 71%, respectively26; and 77% and 82%, respectively15. Therefore, using the lowest of these values, the test gives an incorrect result in either positive or negative direction in approximately 2 of every 10 performed.

It should be noted these sensitivity and specificity values were derived for ACTH concentrations measured 30 minutes after the administration of TRH. It is more common to measure ACTH in samples obtained 10 minutes post-TRH administration and similar values have not been published for this time point.

Additionally, the test is affected by season20,29-32 and seasonally adjusted cut-off values should be used for the interpretation of the result; however, the sensitivity and specificity for these have yet to be published. As a result, it is preferable to avoid performing the test during the autumn rise in pituitary activity, if possible.

ID in equids manifests as hyperinsulinaemia, an excessive insulin response to oral carbohydrate and tissue insulin resistance. Tests should be employed to determine the presence of each manifestation, to decide whether an animal with PPID has ID.

It has previously been suggested basal insulin concentrations should be measured in fasting animals; however, it is now recommended concentrations are measured in animals that have not been fed grain within four hours to detect hyperinsulinaemia.

Previous recommendations of serum insulin concentrations lower than 20μIU/ml being consistent with ID were based on the animal being fasted33. It has been suggested a serum insulin concentration lower than 20μIU/ml is not diagnostic and a dynamic test should be performed; a value between 20μIU/ml and 50μIU/ml is suspicious of ID, but a dynamic test should be performed; and a value greater than 50μIU/ml is consistent with ID (Equine Endocrinology Group). However, it should be noted numerous factors influence serum insulin concentrations, and the sensitivity and specificity of these cut-off values have not been determined.

Additionally, many validated assays are available for the measurement of equine serum insulin concentrations. While the CL assay is commonly used by commercial laboratories in the UK, radioimmunoassays and ELISA are additionally used in research studies.

The values obtained by the various assays are not identical. For example, values obtained using the CL assay are consistently lower than those obtained using radioimmunoassays34,35. Therefore, cut-off values should be specific to the assay used to generate that value and are not universally applicable.

An OST using light corn syrup (0.15ml/kg to 0.45ml/kg) – or an OGT using glucose powder (0.5g/kg to 1g/kg) – can be performed to detect an excessive insulin response to oral carbohydrate. These can be performed either after a three-hour to eight-hour fast, or while the animal remains at pasture36.

Serum insulin concentrations are measured after between 60 minutes and 90 minutes (OST), or 180 minutes (OGT). An insulin concentration greater than 60μIU/ml (0.15ml/kg OST), greater than 110μIU/ml at 60 minutes (0.45ml/kg OST) or 85μIU/ml at 180 minutes (1g/kg OGT) is considered consistent with ID. In one study, the OST and OGT agreed – with respect to binary classification of animals – as ID or insulin-sensitive in 85% of animals37. However, in another study, the repeatability of the OST was poor, with the within-subject coefficient of variation (CV) of the OST at any single time point being 32% when animals remained at pasture or 40% when animals were starved36. The repeatability of the OGT was fair, with the median CV of the insulin concentration at 120 minutes being 19%38.

Additionally, the OST and OGT are affected by season – with greater OST insulin responses occurring in summer, compared to winter, and greater OGT insulin responses occurring in autumn and winter, compared to spring and summer39.

It should be remembered the sensitivity and specificity of these cut-off values have not been reported, and these cut-off values are specific to the assays used in the studies to measure serum insulin concentrations.

The euglycaemic hyperinsulinaemic clamp (EHC) method is the gold standard technique to determine tissue insulin resistance. However, it is not practical to perform in the clinical setting. Instead, an IRT is recommended to detect tissue insulin resistance.

A dose of 0.1IU/kg regular (soluble) insulin is administered IV and the blood glucose concentration measured after 30 minutes. In the single study reporting its use, blood glucose concentrations decreased by more than 50% from baseline in all six normal horses, while the decrease was less than 50% in all six horses with tissue insulin resistance40.

Horses should not be fasted when performing an IRT, as fasting decreased the response to insulin41. It should be acknowledged the IRT has not been compared to the EHC, so its sensitivity and specificity is unknown, and its repeatability has not been reported.

As well as the well-documented effect of season on the output of hormones from the equine pituitary pars intermedia, several other possible reasons exist for the less-than-ideal sensitivity and specificity of the tests available.

Firstly, a lack of histological diagnosis consensus exists for PPID42. As a result, no gold standard exists to validate antemortem tests against.

Secondly, PPID is a progressive disease and diagnostic tests appear to have greater accuracy when applied to cases with more advanced clinical signs. Their sensitivity and specificity in early cases with clinical signs that do not include hypertrichosis have yet to be adequately determined.

Finally, ACTH is not one of the main products of the equine pituitary pars intermedia. Therefore, greater diagnostic accuracy may be achieved by measuring alternative, as-yet undetermined, hormones, or even the plasma POMC peptide signature.

When an animal is presented for the investigation of clinical signs suggestive of PPID, it is important to:

Take an accurate history from the owner to determine the presence of hypertrichosis.

Perform a detailed clinical examination to detect the presence of other clinical signs suggestive of PPID that may have been mistaken for ageing by the owner.

Perform appropriate further diagnostic tests – ensuring, if possible, the animal is not displaying signs of acute laminitis or other concurrent disease that may affect circulating ACTH concentrations. At this point, it is also prudent to ensure the owner understands no single ideal diagnostic test exists, such that the first test is the start of a diagnostic journey and repeat testing may be required.

Interpret the results of the further diagnostic tests, using a seasonally adjusted reference range that maximises the sensitivity and specificity of the test performed. Additionally, the signalment, clinical signs and results of additional further diagnostic tests performed should also be taken into consideration before reaching a final diagnosis.