30 Jun 2021

Jack Reece discusses the case of a chestnut Marwari presenting with a lesion that had grown and was ulcerated.

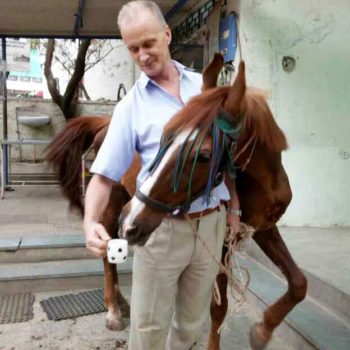

Figure 1. Basanti at first presentation with large tumour and in poor condition.

One of the fun things about working for a charity overseas remotely from referral centres and veterinary colleges is that our veterinary team has to cope with whatever cases present themselves. No easy way exists to send tricky cases to some higher, more experienced authority.

Working, as I do in India – where the profession is not as advanced nor client expectations and trust as high – one of the challenges is that animals are often presented to our veterinary team at a much later stage in a disease than would be the case in this country. And so it was with Basanti, who was brought to the Help in Suffering hospital by her owners.

Basanti is the name we have given the mare since, as is often the case in Rajasthan, the owners had not named the horse. Basanti was a mid‑teens chestnut Marwari mare in lean condition.

The brothers had been using the Marwari mare as a wedding horse in a village some distance from Jaipur. They reported that about 18 months earlier they had noticed a small wound about the size of a thumbnail between the mare’s breast and the point of the shoulder.

Since the lesion’s first appearance they had tried local remedies (ash is popular in such circumstances) and had visited the nearest government vet, who prescribed anti‑fly wound ointment and potassium permanganate crystals topically. But now this small, almost insignificant lesion had grown to be about 9in across and 2in to 3in thick, and was completely ulcerated (Figure 1).

The owners recognised that something had to be done, or more likely considered nothing could be done, and wanted some way to be rid of the horse and its lesion.

We examined Basanti. The growth was ulcerated, clearly heavily infected and in danger of infestation with screw worm fly maggots, a tropical “nasty” that is ubiquitously troublesome in Jaipur. The mare was very thin, and a clinical examination revealed another similar small, grape‑sized, ulcerated skin tumour on her thorax. Both tumours did not feel attached to underlying tissues.

Equine histopathology is non-existent in Jaipur, but this absence was not really an impediment since it was obvious that the breast growth would need surgical intervention whatever it was.

We put the mare on a course of antibiotics and NSAIDs, gave ivermectin to deter maggots and instituted topical wound cleaning. While these all seemed logical treatments prior to surgery, I will admit I saw them as more usefully giving us time to think what to do about this large soft tissue mass in a difficult anatomical position. We are not specialists in anything, but especially not in equine soft tissue surgery or oncology, nor is our hospital really equipped for major equine surgery.

As I expected, a few days of treatment had done little to shrink the ulcerated mass. No doubt existed that the mass would need to be surgically removed. Remembering the great Professor Edwards’ “have a go yourself” answer to a question about what to do with surgical cases where referral was not possible, my colleagues and I prepared ourselves for the surgery.

Although Basanti had proved herself a calm, kind animal, I considered that the growth was too extensive and poorly located to consider surgery under local anaesthetic. Anaesthetising horses is always rather stressful, although so far, in our limited experience at Help in Suffering, we have not had the catastrophic difficulties often reported for general anaesthesia in the horse.

A team was assembled, and all possible equipment prepared. Luckily the Jaipur weather is predictable so that al fresco operating is easily planned, and even in an impoverished charity setting, lots of manpower is always to hand.

The mare was anaesthetised using a xylazine ketamine combination IV (Figure 2). My colleague Sanjay Singh and I had decided that dorsal recumbency would be necessary to get at the mass, and to facilitate skin reconstruction. While the team positioned the horse, and restrained her with ropes and sandbags, we scrubbed up and prepared our instruments, usually used for spaying dogs.

Sometime previously we had received a donation of large disposable surgical drapes; these we used to shield most of the area from gross contamination while draping the surgical field with our smaller sterile cloth drapes.

Together from opposite sides, Dr Singh and I started the excision (Figures 3a and 3b). Wide margins and elegant incisions were not really possible, neither was it possible to take precautions against “seeding” the tumour into surrounding tissues as we excavated the mass.

As our initial palpation of the large mass had suggested, it had not obviously invaded underlying tissues and had no dramatic blood vessels. Indeed, removing the dinner plate of ulcerated tissue proved relatively easy. Suturing the resultant wound, however, was a long and tiresome process, not least because we had no surgical needles suitable for equine use (Figure 4).

Tension-relieving sutures were placed deep within the wound, but even these – and some further undermining of skin – would not allow us to close completely the large hole and considerable skin deficit we had created. Eventually, after an operation lasting about two-and-a-half hours, Dr Singh and I decided we could effect no better closure.

After so long kneeling or squatting on the floor, we were glad to stand up; would, however, the mare do so? No gas anaesthesia, no additional oxygen to maintain partial pressure of oxygen, no pneumatic mattresses, prolonged dorsal recumbency, indeed field surgery – I recall all are ill-advised by equine anaesthetists.

We rolled her on to her brisket and waited quietly… and waited, and waited. Eventually, after about two hours, she lurched unsteadily to her feet, only to sit back down again, but then a few minutes later she arose unsteadily, but permanently, and in doing so ruptured some of the sutures we had so laboriously placed, enlarging the hole we had been forced to leave to heal by second intention.

Weeks of daily dressing followed as we wondered if the mass, which we had concluded must be some type of sarcoid, would regrow. Basanti never flinched at the daily dressing and examinations – indeed, she seemed to enjoy the company and attention.

After about six weeks the wound had healed, leaving a large, pale, untidy scar. However, as the area settled down it was apparent that there were many small tumours in the skin in a ring surrounding the initial site (Figure 5).

Through former volunteer vet Danny Chambers, we consulted Veronica Roberts, equine expert at the University of Bristol Veterinary School, by email. They suggested we use 5-fluoruracil cream topically on each new tumour. We could not obtain such cream, but could obtain the drug in injectable form.

With email guidance again from the University of Bristol, we “invented” an equine intralesional dose extrapolating from published human skin tumour treatments. Dr Singh then began a series of multiple injections into the tumours every five days (Figure 6). Many small nodules were under the skin – each was injected.

Provided she could not see what was happening, Basanti accepted this regular, time-consuming treatment. After five such rounds of injections, the small tumours had gone (Figure 7) and Basanti was still well in herself – indeed, with the improved hospital diet she had put on considerable weight and now had a lustrous, glossy, chestnut coat.

Our advisors warned that all our treatments would be palliative, so we kept a very close watch over Basanti’s skin. Every little bump or thickening made us wonder if the tumour was returning. A nodule under the original surgical site was detected and injected, although whether it was tumour or scar tissue we were unsure.

Then a round, flaky lesion was found in the skin of the throat. Was this an occult sarcoid? Was it related to the earlier large growth? We watched and waited, and were relieved when this throat lesion recovered – it had been only a scab.

Curiously, the small flank lesion did not respond to the 5-fluorouracil and Dr Singh later surgically excised it under local anaesthetic. Basanti had settled into hospital life and seemed to enjoy the attention. The earlier secondaries had appeared within six weeks of our interfering with the large 9in tumour.

Six months after they were treated, no further tumours have arisen, but we continue to monitor carefully. Basanti’s owners have abandoned her – we have contacted them, but they are not interested.

The Help in Suffering compound is a hospital and we try not to acquire too many residents, but we have turned down offers to adopt Basanti so we can keep her at Help in Suffering, despite the expense, and continue to monitor her condition, believing the expert opinion that they will recur and that when they do they will be, as before, a serious welfare problem.

Meanwhile, we enjoy her company and she ours (or so we would like to think; Figure 8).

Our great thanks to Dr Chambers and Dr Roberts for their advice from afar.

Information on the work of Help in Suffering and how to be involved can be found at www.his-india.in