27 Nov 2017

Elizabeth Jackson discusses a study into professionals’ perceptions of how this method helps organisational aspects of practice.

IMAGE: RVC.

This mixed-method research was principally focused on understanding the perceptions of the veterinary profession to the non-clinical benefits of evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM), in terms of:

Results from a survey of 407 veterinary professionals suggested the practice of EBVM is a virtue for supporting initiatives aimed at improving the work environment of the UK veterinary profession. No suggestion is made herein that business performance will be increased as a result of implementing EBVM. We do, however, recommend encouraging the practice of EBVM as it closely aligns with the values of so many initiatives being undertaken in the profession, such as Vet Futures and the Mind Matters Initiative.

Further analysis, including cost-effectiveness, is needed to investigate the financial benefits of specific aspects of EBVM. As the results of this study portray the opinions of veterinary professionals, further research is needed to obtain the perspective of clients – to test whether clients are aware of EBVM and how the practice of EBVM is viewed by clients.

While extensive knowledge exists about the clinical benefits of evidence-based veterinary medicine (EBVM), the non-clinical benefits are far less clear.

The non-clinical benefits of evidence-based human medicine (EBM) have been briefly considered. Caldwell (2001) discussed EBM from an organisational context, in that practising good medicine can only be a function of the convergence of health care systems that focus on measuring customer loyalty, patient safety, clinical excellence, productivity, market growth and rate of improvement.

McCracken (2013) picked up on a key theme discussed by Caldwell (2001) – elimination of waste. Both authors advocated cost savings brought about by EBM, in terms of minimising the burden of overtreatment, failures of care coordination, failures in the execution of care processes, minimising administrative complexity, pricing failures and fraud.

The PICO process is a technique used in evidence-based practice to frame and answer a clinical or health care-related question. The framework is also used to develop literature search strategies.

The PICO acronym stands for:

P – patient, problem or population

I – intervention

C – comparison, control or comparator

O – outcome

While these authors presented an appetising introduction to the non-clinical benefits of EBVM, their publications lacked rigour, so a PICO-based literature review (Hauser and Jackson, 2016; Panel 1) dug deeper into the knowledge of the non-clinical benefits of EBVM.

Some papers have suggested a link between the practice of EBVM and better non-clinical benefits, such as client satisfaction, but a study focusing on the non-clinical benefits of EBVM was yet to be conducted. This research tried to fill this gap in knowledge.

In such an understudied area of knowledge, research design is critical to ensure a breadth of knowledge from veterinary professionals is sourced. However, the study also considered an appropriate depth of knowledge to ensure valid and reliable results.

As such, a two-phase, mixed method approach to the research was taken. Ethical approval was provided by the RVC’s clinical research ethical review board.

The first phase was qualitative, involving 16 expert interviews with veterinary professionals dedicated to the practice of EBVM. Interviews allowed for a rich, detailed exploration of the unknown dimensions of EBVM. Participants were able to speak freely about their experiences of EBVM and their perceptions of the barriers to adoption in both clinical and non-clinical contexts.

The findings from this phase of the research were used to construct a survey to test and confirm the sentiments of the EBVM experts. The online survey consisted of 23 questions and yielded 407 usable responses from veterinary professionals; the sample was generally representative of the demographic of the UK veterinary professions, with most responses from the small animal health care sector.

The qualitative, exploratory phase of the research yielded some unexpected findings about the non-clinical benefits of EBVM (Jackson and Hauser, 2017). Discussions principally revolved around how EBVM can improve the quality of service to clients. Improved client satisfaction and retention were discussed in terms of saving clients money, the perception of value held by clients, trust, client appreciation, and the veterinary professional being able to overcome the unknown.

The positive reputation of the practice and its veterinary professionals also emerged as a key theme. Issues surrounding this were associated with the client-friendly approach to veterinary medicine brought about by adopting EBVM, trusted clinical practice and reliable procedures.

Most interestingly, a lot of evidence emerged about how vets’ confidence was developed from the application of EBVM and how it was a valuable opportunity to stimulate engaging, challenging discussions with colleagues.

The data for the quantitative phase of the research were collected from 407 veterinary professionals. Of these, 59% were female, 39.8% male and 1.2% preferred not to answer the question. Respondents’ ages ranged from 21 to 76. The average age was 41.3 years, with most participants (33%) aged 30 to 39. The sample included vets (86.5%), veterinary nurses (12.8%) and students pursuing a veterinary or veterinary nursing degree (0.7%). Most respondents worked with small animals (77.8%), followed by those working in equine (8.1%), mixed (5.2%) and farm animal practices (3.7%), and other fields (5.2%) including academia, laboratories, exotics and practice management.

Half of all respondents were employees (50.4%), the second largest group were owners or joint partners (39.6%), and 10.1% were in other working arrangements, such as locum, retired, self-employed or in academia. The veterinary professionals mainly worked in independent (58.4%) and corporate veterinary practices (27.6%), with some in academia (8.9%) and other roles, including Government (5.2%).

For the purpose of analysis, respondents were divided into two groups based on whether they actively practise EBVM. Of the 405 participants who responded to this question on practising EBVM, those who answered “yes” were considered to be actively practising EBVM (n = 282, 69.6%), whereas those who answered “no” (n = 16, 4%) or “unsure” (n = 107, 26.4%) were considered not to actively be practising EBVM.

The data yielded a great deal of results about the perceptions of the EBVM held by veterinary professionals. The findings of the qualitative phase provided a strong basis for the survey and ensured the data collected were grounded in real-world practitioner experience.

Most participants (77.1%) either strongly agreed or agreed to the question: “I practise veterinary medicine in a way that is supported by published evidence.” This was a positive finding for the proponents of EBVM.

Of all the questions related to EBVM in clinical practice, a significant difference existed between those who practise EBVM and those who do not. For example, those who practise EBVM are more likely to consult the literature when faced with a challenging case, spend more time per month considering the literature, are more likely to contribute to scientific literature and are more likely to have done so in the past 12 months.

Furthermore, those who were taught how to practise EBVM at university were also more likely to practise EBVM; thus, a direct link between university teaching and practising EBVM can be drawn.

In terms of understanding EBVM, it was largely agreed clients are unaware of this type of veterinary practice, while no evidence existed to suggest clients appreciate an evidence-based approach or veterinary professionals perceive EBVM saves the client money. However, evidence emerged to suggest veterinary professionals believe clients appreciate the extra work that goes into researching their specific case, and EBVM builds trust with clients.

When it comes to veterinary professionals’ perception of EBVM, the data suggested EBVM helps overcome the unknown. This statement attracted support from those practising and not practising EBVM, suggesting this approach to veterinary medicine is bilaterally considered a good approach for overcoming the unknown.

One highlight of this research was the finding practising EBVM contributes to positive employee engagement, with overwhelming support for the notion EBVM helps veterinary professionals feel they are doing a good job in terms of providing the best medical care for the patient, providing confidence in clinical decision-making, developing good workplace bonds by sharing knowledge, and providing an intellectual challenge to the job.

Much scope exists for further research into this finding, but this suggests providing employees with an EBVM environment positively contributes to how they feel about their work. It was found a way to nurture this is for employers to provide paid time for practising EBVM and provide training opportunities.

Barriers to the adoption of practising EBVM were also investigated. The qualitative phase of the research revealed a number of potential reasons for veterinary professionals not adopting EBVM, but the quantitative phase showed many of these – such as “clients do not want lengthy, diagnosis-laden treatment options”, “the evidence available is often of low quality” and whether EBVM is taught at veterinary schools – attracted neutral responses. Evidence from the qualitative research that attracted more positive responses was insufficient time in daily practice to practise EBVM and definite scope for adapting EBVM to include veterinary paraprofessionals.

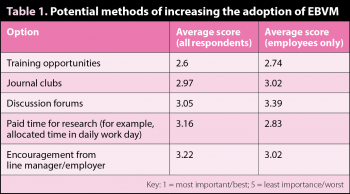

In terms of overcoming these barriers, the qualitative data suggested a number of methods that could help. Survey participants were asked to rank these from best (1) to worst (5). Since so many respondents were practice owners, the data were also considered from an employee-only perspective. Results are presented in Table 1.

When data including and excluding owners were considered, training opportunities for increasing the adoption of EBVM was the highest ranked answer. Rankings varied when the data were separated, with employees rating “paid time for research” second to “training opportunities”, whereas “journal clubs” ranked second when owners were included in the sample. The researchers predicted “encouragement from my line manager/employer” would rate far stronger than the results showed.

Overall, the findings indicated the two types of veterinary professionals have different attitudes towards overcoming the barriers to the adoption of EBVM.

This research principally focused on understanding the perceptions of the veterinary professions to the non-clinical benefits of EBVM in terms of how EBVM is practised, how EBVM impacts client behaviour and employee engagement, the barriers to practising EBVM, and how these could be overcome.

Reflecting on the work of Caldwell (2001) and McCracken (2013), no evidence was found practising EBVM improves customer loyalty, patient safety, clinical excellence, productivity, market growth or waste management. On the other hand, this research is the first to reveal the human factors enjoyed by practising EBVM – it was found it provides an intellectual challenge for veterinary professionals and instils a sense of confidence in their daily activities, as well as creating a collegiate atmosphere in which professionals are motivated to share their ideas and experiences.

This closely aligns with the values espoused by the Vet Futures and Mind Matters initiatives, whereby people’s well-being is at the heart of new thinking in the veterinary professions. Themes such as confidence, leadership, resilience and well-supported feature prominently in plans for the future, and this research has shown EBVM as a potential conduit for developing such values.

Another theme discussed by Vet Futures (2015) is “thriving, innovative, user-focused business”. The research did not yield conclusive knowledge that builds a business case for the adoption of EBVM, but subsequent work would be well-placed to investigate financial returns and client satisfaction from practising EBVM.

RCVS Knowledge is gratefully acknowledged for its support of this research, as are the project’s co-investigators – Sarah Hauser BSc(Hons), MPA, MPP, and Graham Milligan MA, VetMB, MRCVS – and all the interview and survey participants. The author is also grateful to veterinary practices that circulated the survey to staff.