30 Jul 2024

Ann Derham looks at both the diagnosis and treatment options available for respiratory problems in equids.

Image © Margaret Burlingham / Adobe Stock

Upper airway conditions are relatively common in horses and can be described based on their location in the upper airway. Many conditions can cause issues while the horse is at rest, while some are only an issue during physical exertion.

This article is aimed at discussing how to diagnose upper airway conditions in horses, and treatment options available.

Some of the more common upper airway conditions in horses are:

As with any condition, a thorough clinical examination and careful history is critical in narrowing down the differential list and establishing the most logical diagnostic approach.

For example, a dynamic endoscopy of the horse would be deemed unnecessary in a horse suffering from a sinusitis, while it would be warranted in a horse that is making a noise at exercise and exercise intolerance.

A thorough history should include the following questions:

A clinical examination can provide some useful clues:

Once all the pertinent questions have been answered and the clinical examination performed, a diagnostic plan can be put together and should involve some/all of the following:

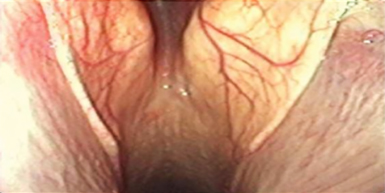

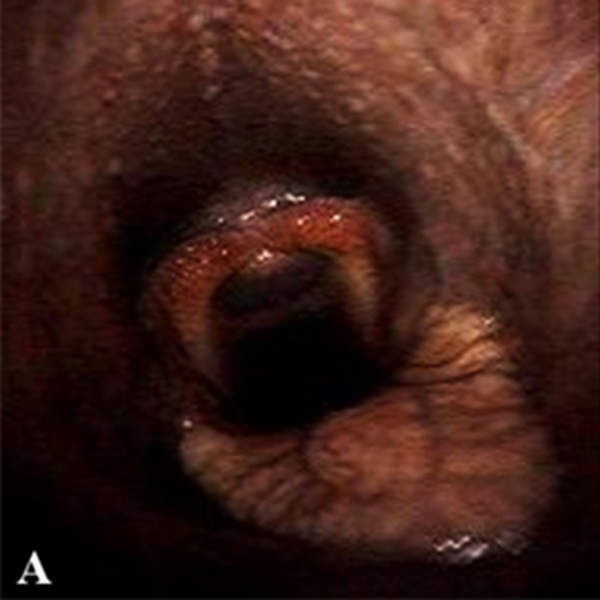

Figure 2. Some examples of resting endoscopy. (2a). Rostral displacement of the palatopharyngeal arch. (2b). Assessment of the guttural pouch openings. (2c). Sub-epiglottic ulceration.

It is important to remember that when investigating DDSP or RLN, the endoscopic exam must be performed unsedated. When assessing arytenoid function, the horse should be made to swallow so that degree of abduction can be assessed (Havemyer scale).

Figure 4. Dynamic endoscopy stills from the same animal. (4a). Normal appearance of pharynx early on in exercise. (4b). Dorsal displacement of the soft palate in the same horse further into work.

The alar folds are resected, either under general anaesthesia or standing sedation.

A novel technique involving placement of a suture into the alae, resulting in permanent tying up of the fold, is under investigation.

Intralesional 10% formalin has been reported. Surgical options include removal via a skin incision (Figures 1a and 1b), or lancing the cyst into the nasal diverticulum, everting the lining and removing it. Regardless of surgical technique used, the lining must be removed in its entirety to avoid recurrence.

Intralesional 10% formalin has been used; however, it is contraindicated if the cribriform plate is disrupted.

Many are surgically removed following accurate identification of the origin of the mass, and usually done through a nasal bone flap.

Several approaches are available when treating guttural pouch conditions. Temporary treatment of tympany involves needle decompression or placing an indwelling foley catheter.

Laser fenestration to create a permanent opening of the guttural pouches can also be done to treat this condition, which can also be used to treat certain cases of guttural pouch mycosis (a viable option when arterial occlusion techniques are not available or are too costly, and the horse is clinically stable).

Empyema usually requires surgical access to the pouch to effectively evacuate inspissated material (hyovertebrotomy, Whitehouse, Viborg triangle, modified Whitehouse). Endoscopic approaches have been suggested, but can be extremely long and laborious, and may need to be done over several days.

Mycosis typically presents as an emergency due to a catastrophic haemorrhage and surgical intervention is necessary.

Several options are available that involve ligation/occlusion of the affected artery(ies), the treatment of choice is largely dependent on available equipment, imaging and finances.

If the horse is stable, and not in need of emergency surgery, more conservative approaches may be undertaken, such as topical antifungal therapy or guttural pouch fenestration.

Treatment options are largely based on the issue (noise complaint, poor performance or both), the degree of paralysis, horse’s age and performance use.

Ventriculocordectomy is mostly used in sport horses, where noise is the main complaint, but will also result in some improvement in airflow through the larynx.

The ventriculocordectomy can be performed either via a laryngotomy (typically done anaesthetised) or using laser resection via endoscopy under standing sedation (Figure 5).

Prosthetic laryngoplasty (tie-back), results in significant improvement in airflow, and is the most appropriate treatment for racehorses with Havemeyer G3 or worse, or in any horse where there is complete paralysis of the arytenoid. Originally, this surgery was performed under general anaesthesia, but is largely done with standing sedation and local anaesthesia nowadays.

Ideal abduction is considered a G2 Dixon scale (88% abduction), as this avoids complications associated with over-abduction. A ventriculocordectomy is performed as well in these cases. The drawback to this procedure is the risk for postoperative complications such as persistent coughing, dysphagia, implant failure and seroma.

Cricoarytenoideus dorsalis (CAD) muscle re-innervation (Figure 6) provides an exciting alternative to the laryngoplasty, avoiding the use of implants and potential complications associated with the laryngoplasty procedure.

The re-innervation technique originally used a branch of C1-C2, which is inactive at rest, so horses require exercise to rehab the muscle, whereas more recently the ventral branch of the spinal accessory nerve has been used to overcome this.

The re-innervation procedure cannot be performed in horses after a previous tie-back procedure, as the nerves are disrupted during the surgical approach and resulting fibrosis makes it difficult to perform. A drawback to this procedure is that it requires a longer postoperative convalescence, and if the procedure fails, a tie-back will be required.

Ideally, the surgery is best suited to younger animals, which can afford to have a longer convalescence, with Grade 3 cases being shown to respond better than those with Grade 4 laryngeal function (Havemeyer).

Fourth branchial arch defect is a condition resulting in abnormal development of the larynx. These horses typically present for a noise made at exercise +/− exercise intolerance.

Endoscopy may show right-sided/bilateral/left-sided hemiplegia; however, unlike RLN, this is due to abnormalities of the joint and not a CAD muscle issue. Rostral displacement of the palatopharyngeal arch is also seen (Figure 2a). Treatment depends on the severity of the dysplasia, right or left-sided laryngoplasty; however, the surgery may not be an option due to abnormalities at the sites of suture placement.

Axial deviation of the AEFs causes an abnormal respiratory noise at exercise and loss in performance. This condition cannot be seen at rest and is only diagnosed on dynamic endoscopy. Treatment is surgical removal of the folds either through a laryngotomy or transendoscopic laser resection.

Epiglottic entrapment is where the dorsal surface of the epiglottis becomes covered by loose aryepiglottic mucosa. Horses typically present with a respiratory noise, coughing and exercise intolerance, but in some cases, it may be an incidental finding.

This is readily diagnosed on resting endoscopy – the epiglottis will be visible, but the dorsal vascular pattern is no longer observed. Treatment involves transecting the tissue midline, either with a guarded hook-knife or using transendoscopic laser.

Surgery (epiglottopexy) has been attempted to tie the epiglottis down to stop the retroversion but has been largely unsuccessful (Figure 7).

Subepiglottic cysts, depending on the size of the lesion, can lead to respiratory noise at exercise, cause DDSP or significant respiratory obstruction. It is diagnosed via endoscopy and/or on radiographs.

Treatments options include puncturing and draining the cyst; however, like any cystic structure, if the lining is not removed/ablated, it will refill.

Cysts can also be injected endoscopically using formalin (>1 treatment), or it can be removed surgically via a laryngotomy or transendoscopically.

DDSP is difficult to diagnose at rest – resting endoscopy can lead to false negatives/positives.

Most horses typically make an expiratory noise at exercise, but it should be noted that approximately 30% of affected horses will not make noise at exercise. Often, horses are reported to have a sudden performance loss at high speed.

Diagnostics include unsedated resting endoscopy where the horse may displace and be unable to self-correct, or there may be ulcers at the caudal border of the soft palate. However, the gold standard remains dynamic endoscopy (Figure 4).

An array of treatment options are available for DDSP, with no one option proving significantly better than the other. Conservative options look at reducing any pharyngeal inflammation (steroids, anti-inflammatories), waiting until the horse is either more mature, stronger and/or fitter and then reassessing.

Tack adjustments include figure-of-eight/dropped nosebands and tongue-ties. Surgical options include thermocautery of the soft palate to induce fibrosis, myectomy of the sternothyrohyoideus muscle to reduce the caudal pull of the larynx (standing or general anaesthetic) or laryngeal tie-forward where a prosthesis replaces the action of the thyrohyoideus muscles and pulls the thyroid cartilage dorsally and rostrally.

A variety of conditions can affect the upper airways of horses. A thorough history will help pinpoint the problem, along with using the best diagnostics possible.

It is important to be aware that many airway conditions occur during exercise only, and dynamic endoscopy is needed for an accurate diagnosis, followed by appropriate treatment.