16 Aug 2022

Cows’ feet have never been so popular, with social media accounts devoted to hoof trimming. Ironically, vets have increasingly become disenfranchised from bovine foot health – but here, Owen Atkinson says why that should now change.

Figure 1. A severely overtrimmed foot, treated by a hoof trimmer. An iatrogenic lesion is on the white line of the outer claw (without the block), which was caused by an electric rotary rasp (“grinder”) and this has caused severe lameness.

Cows’ feet are trending. This is a phenomenon I never thought I would live to see, but it is true. If you want to be where the smart kids are, you’d better get into cattle foot health.

My first inkling was a few months ago when I took my daughter to the orthodontist. The dentist – a smart young man in his 30s – asked me what I did for a living. Every vet knows the mixed feelings about whether to answer this question truthfully and face some inevitable remarks about putting hands up cows’ backsides, or to fib and thereby duck the inevitable clichés. On this occasion, though, I didn’t say I was a dustman and I told the truth.

“I’m a vet,” I said.

“Wow,” my daughter’s dentist replied. “Do you ever do surgery on cows’ feet?”

Now that took me aback. Only a small fraction of vets nowadays are in farm practice, and an even smaller fraction regularly do surgery on cows’ feet. I just happen to be one of them.

Thereupon we embarked on a lovely conversation about white line abscesses, complicated non-healing claw lesions and necrotic toes.

“Have you ever met The Hoof GP?” he asked. Had I ever seen @thefemalehooftrimmer, he enquired, and what about Nate the Hoof Guy?

It turns out that this young dentist and his wife enjoy their precious evenings, not watching Bake Off, but snuggling up on the sofa to pore over YouTube videos of hoof trimming. And they are not alone, it seems. BBC News has also run a story about a Cornish hoof trimmer whose TikTok videos regularly go viral. The Hoof GP has more than two million subscribers to his YouTube channel (and consequently has a stable of very expensive sports cars, as well as his pick-up and foot crush).

This happy episode concluded with a very rare compliment from my teenage daughter when we walked out of the surgery.

“Blimey Dad, I thought no one except you was interested in cows’ feet. That was cool.”

Well, I took that as a compliment anyway – it’s the closest I get these days.

Despite the fact that cows’ feet are now apparently in vogue, vets struggle to get a look-in on cattle foot health these days. It is a sign of the times, and is a problem I see for myself when I teach the BCVA Foundation Lameness module each year. Maybe five years ago, while delegates generally did not feel confident about their hoof-trimming skills, most had treated a cow’s foot in some description during the previous six months. Now, hardly any recent graduate farm vet can say they get even that limited exposure.

Vets becoming disenfranchised over cattle hoof care is a problem that has been reported in North America, too (Wynands et al, 2021).

And yet, as vets, we are the ones who should be overseeing bovine foot health. How can we continue to do this if we do not have the experience of trimming or treating individual lame cows? I have two answers to that. The first is that foot health is far more than simply trimming. Vets can and do bring a huge amount to the party without needing to treat individual cows. The second answer is less assured: vets do need to understand foot trimming and treatments to stay relevant here and, in my firm opinion, to safeguard cow health and welfare.

Unfortunately, a lot of bad trimming is going on, and to ignore trimming technique when dealing with foot health is to potentially miss a huge piece of the jigsaw (Figures 1 and 2).

The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB; formerly DairyCo) Healthy Feet Programme (HFP) is the pre-eminent national framework for vets to help farmers improve dairy cow foot health. It was developed in 2011, and 11 years on, it is a good time to reflect on what it has achieved, and where it is going. First of all, it’s probably a good idea to give a brief history and overview of the programme – especially for those readers who are less familiar with it.

In 2006-10, The Healthy Feet Project at the University of Bristol, supported by The Tubney Charitable Trust, laid the foundations for the programme. This work, alongside other programmes that were evolving in New Zealand and the Netherlands, was progressed into the DairyCo Healthy Feet Programme, as it became known, for launch in 2011.

The programme is essentially a blueprint for how to work with farmers to reduce lameness. At the heart of it is an action plan, but this doesn’t just magic out of thin air – and we all understand that what is important on one farm might not be so important on another. Plus, a plan is one thing – actually carrying it out is another thing entirely.

For this reason, the programme is delivered to farmers by trained Mobility Mentors, who are mainly vets, but include a handful of professional foot trimmers. Mobility Mentors are trained to combine sound knowledge about bovine foot health with mentoring skills to help farmers develop a plan that will work – and that they will do.

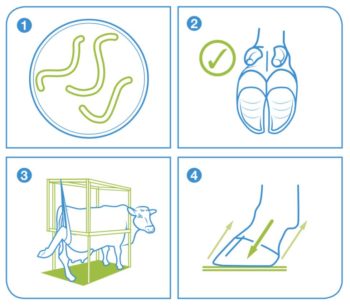

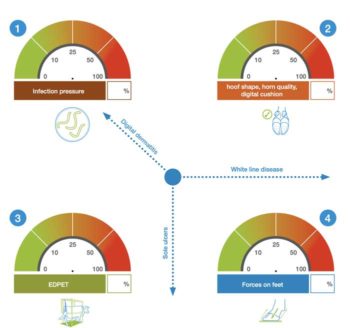

The four success factors for foot health are central to the programme (Figure 3). These are low infection pressure; a robust foot; low forces; and early detection, prompt effective treatment. A lameness map (Figure 4), using lesion prevalence data, assists in targeting the actions and changes that will be most beneficial for the farm. Regular whole-herd independent mobility scores track progress and aid discussions about the economic impacts, using the HFP cost calculator. Finally, various supporting materials that help farmers understand more about lameness, and how best to tackle it, are available – for example, the AHDB hoof care field guide, and information on tracks, footbaths and different lesions.

In 2020, a revamped HFP was inaugurated alongside a scaled-back HFP-Lite to reach a greater number of farms and to share latest knowledge. The branding changed, too, which reflected the change to the AHDB (Figure 5). Training of Mobility Mentors was taken on by the BCVA, and much broader collaboration now exists between the BCVA and AHDB over the running of the programme.

The HFP is supported by a mobility steering group with representation from farmers, processors, retailers, academics, regulators and assurance bodies. More than 180 people are trained Mobility Mentors, and the programme has been fully delivered on an estimated 10% of farms in Great Britain, with many others benefiting from partial delivery.

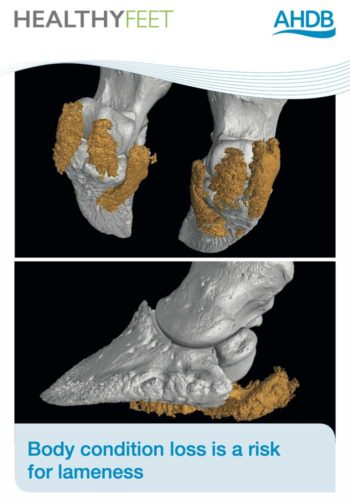

The supporting resources – both printed and online – are some of the most requested of all AHDB Dairy materials. They have been important in helping to successfully roll out the latest lameness research findings directly on to farm. Examples include the effects of low body condition score on lameness risk and the importance of the digital cushion (Figure 6).

Back in 2013, a Northwest Regional Development Agency study looked at the effects the programme had on farms, in essence asking whether it works and what farmers thought about it (Atkinson and Fisher, 2013).

At that time, it was found that farms that participated in the programme reduced overall lameness after one year by an average of 22%, compared with a matched set of farms that on average saw no change. All participating farms interviewed after a year said working with a mobility mentor had benefited the farm, with an average return on investment of 300% (investment being the cost for doing the programme, plus any costs associated with changes made). In short, the study found that it does work, and farmers like it once they are persuaded to do it.

Some Mobility Mentors have dropped off the radar – possibly due to coming out of vet practice or a change in roles – but the vast majority are still engaged. They have access to expert technical support and regular technical updates, through newsletters, a dedicated WhatsApp group and specific CPD opportunities. This has helped to nurture a community of professionals who have become the go-to people for lameness management. It would be good to have more of them.

Alongside all this, it is fair to say that mobility scoring has moved on quite a bit, too. Mobility scoring is now mainstream among many dairy farms in Great Britain, and is supported by the Register of Mobility Scorers (RoMS), which brings standardisation and professionalism to this important task. Still more work needs to be done to get consistency among scorers, and where it is used just to satisfy a milk contract and to “tick the box”, its true value is still not being achieved.

Where it is used properly, a comparison might be that mobility scoring is to lameness management what individual cell counts are to udder health management. The value is in collecting prevalence data, plus being able to identify cows for early treatment. New technologies have the potential to detect lame cows more objectively than a human observer, and these developments are welcomed.

Some of the challenges over the years have been due to internal changes within DairyCo/the AHDB. At times, the programme has received so little funding or support that it has been in danger of disappearing. Currently, it seems to be in a good place with the support of the BCVA. The main challenge is probably the same as it always has been, though, and that is that lameness is not always prioritised (or recognised) in farmers’ minds and that its economic impact is often massively under-estimated. Encouraging more farmers to undertake the Healthy Feet Programme remains a priority – with plenty still to do and many more farmers to reach.

Alongside the trending of cows’ feet on social media, maybe we are starting to see a slight shift in prioritisation among farmers, too. A greater recognition exists that lameness costs the industry a huge amount, as well as being a welfare problem, and a potential blight on dairy farming’s reputation. In 2021, the Ruminant Health and Welfare “grassroots” survey found lameness was the top health syndrome of concern for consultants, vets and dairy farmers, with digital dermatitis heading up the list of priorities when it came to individual diseases too (Miller, 2021).

Elsewhere, work conducted by the Royal Agricultural University, Cirencester, on behalf of AHDB, resulted in several farmer-led recommendations for reducing lameness (Williams van Dijk, 2020). These included that the ability to deliver the HFP should be a standard requirement for all vet practices providing services to dairy clients.

More vets are encouraged to train to become Mobility Mentors, and farmers are encouraged to take up the programme wherever possible. At the end of the day, it has been shown to work, and give a good pay back. It can be very satisfying work to do as well, improving as it does cow welfare and farm sustainability.

So, where next? My own belief is a lot still needs to be done to tackle lameness in the dairy industry, and sometimes it can feel like we are not getting anywhere. However, looking back, it is easier to see how things have improved.

Definitely, greater awareness exists of the true causes of lameness (less talk about excess protein and laminitis and all that rubbish), and we have seen some great examples of individual farmers who keep lameness remarkably well managed. Managing lameness is only going to move up the agenda in the coming years. I encourage all dairy farm vets to get behind the HFP: promote it; use it; become a mobility mentor.

In terms of foot trimming skills, the BCVA is working to develop training programmes specifically for dairy vets, so they can gain confidence in assessing trimming technique. Farmers themselves and hoof trimmers will continue to be doing the vast majority of day-to-day hoof care, but vets must be able to oversee this. Vets and professional trimmers must be able to work alongside each other, both confident in each others’ expertise.

In an ideal world, we would have trimmers only working in a vet-led team, and we would have robust accreditation for both professional trimmers and on-farm staff who wield a hoof knife or grinder. Those goals seem a long way off, but we should still articulate them when we can – and work towards them.

Presently, no legal prerequisites to become a cattle hoof trimmer exist. Farm workers, too, grind cows’ feet without training or proper guidance. People learn from YouTube clips and, unfortunately, more examples online exist of dangerous or harmful trimming than of best practice. The situation is far from ideal.

So, as I often conclude when I write these articles on cattle lameness, I urge all cattle vets to take an interest in, and get properly trained up on, cattle hoof care. Only this time, I can say with confidence that if you do, and if you have a teenage daughter, she might begin to think you’re quite cool.

If you would like to train to become a mobility mentor, check out the BCVA website (www.bcva.org.uk), contact the BCVA directly, or contact the author ([email protected]) or Nick Bell ([email protected]).