11 Sept 2017

Removing BVD from the UK herd would go a long way in improving cow fertility, productivity and calf health and welfare, says Alex Perkins.

A pestivirus of high genetic variability (others include classical swine fever and border disease of sheep), first reports of bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) in 1953 were of an acute, highly infectious diarrhoea where most animals recovered quickly, although between 4% to 8% died of the disease, called mucosal disease.

These days, practitioners generally accept diarrhoea as being a less common presentation, with fertility issues and calf health more often flagging up questions over BVD status of a herd. As far back as 1956, abortions were identified to be a consistent finding in herds with disease outbreak, with transplacental infection demonstrated in the 1970s. It is these presentations of disease that lead to massive economic disruption on a farm, as the ramifications of poor fertility and production in cows and a weakened immune function in the calf are widespread, and affect far more than the viraemic animal.

Non-pregnant animals encountering the disease will not suffer marked clinical disease. There maybe pyrexia, leukopenia from days three to seven and limited recovery of the virus from nasal secretions during the first three to 10 days. The immunosuppressive effects make animals more susceptible to other infections, such as pneumonia and enteric disease, and links have been made to increased incidence of TB in the herd affected by BVD. In the adult cow you may see milk drop or scour, and reproductive losses.

In the calf with dual infections (BVD and pneumonia/scours) there will likely be more significant morbidity and mortality. The importance of these transient infections should not be underestimated, however, as they are responsible for 93% of all in utero infections that result in the birth of PI calves (Grotelueschen et al, 1998).

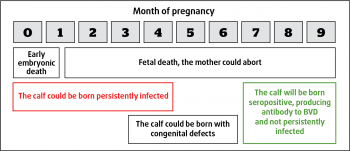

In utero infection of the calf can lead to quite different outcomes (Figure 1) with early infection leading to abortion, fetal reabsorption or stillbirth. Very late infection (more than six months gestation) may still result in a normal calf. Calves infected in early/mid pregnancy may develop congenital defects of neurological or limb deformities.

The other crucially important subset of calves are infected before immunocompetence has developed (around 120 days), but survive to birth and may well reach full adulthood. They are demonstrated to be immunotolerant to the virus, not producing antibodies, and effectively being persistently infected (PI) calves. It is these calves that could go on to develop mucosal disease and are pivotal in the spread and control of the disease. These PI animals may look classically poorly grown or sickly, but equally may keep up with their peers well, therefore making it into the main herd and going on to produce further PIs.

Maintenance and propagation in a herd is by the PI animal that effectively acts as a super-shedder by excreting virus in its bodily secretions, including nasal discharge and faeces. The virus is thought to be able to survive in cold, damp conditions outside the animal for up to three to four weeks.

There are two distinct species of BVD virus pertaining mostly to the geographical distribution of the virus. BVDV-1a types have a worldwide distribution, with the majority of isolates found in the UK belonging to the BVDV-1a group. BVDV-2 viruses were historically restricted to the US and Canada, and although it was known to be active in the UK in 2007, more recent studies have failed to identify it actively circulating here. However, with international movements of cattle it remains a significant risk to UK cattle.

Furthermore, two distinct biotypes are noted for each species of BVDV. The non-cytopathic, persisting in the cattle population in the form of PIs, and the cytopathic biotype, arising after a variety of mutation events or recombination with other BVDV strains that can go on to cause mucosal disease in the PI animal.

BVD is considered widespread in the UK, with 90% of herds showing some exposure to the virus and 65% of herds potentially have a PI present with antibody levels suggesting recent infection. Estimations of the prevalence of PIs within those herds are between 0.3% to 3%.

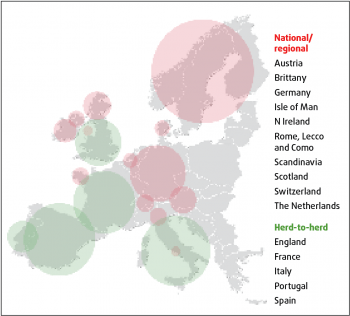

BVD is widespread in North America and some central European countries, yet other countries launched large-scale eradication schemes as long ago as 1993. The Shetland Isles, Denmark, Finland Norway and Sweden led the way. Despite differences in legal support and initial prevalence (ranging from 1% to 50%), these countries have entered final phases of eradication (Figure 2).

More locally, Scotland, the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland already have mandatory, government-led programmes in place and this has led to trade disparities; currently animals in some markets may attract a premium of up to £50 per head when they can demonstrate they tested BVDv negative.

Wales has an industry-led voluntary programme, which launched in July. Testing is due to start in September, with every farm encouraged to screen test at annual TB tests and results being made available at TB reading day to allow discussion on farm. Farms testing positive will then receive funding of up to £500 from the Welsh Government’s Rural Development Programme to identify PI animals.

Earlier this year, England launched the voluntary, industry-led BVDFree England Scheme (www.bvdfree.org.uk), asking individual farmers to sign up to a national database where BVD statuses are easily accessible. The scheme aims to facilitate eradication by 2022. Talks are underway to engage the Animal Health and Welfare Board to decide when it might be appropriate to make the scheme compulsory, for example, once 60% or 90% of farms are signed up. Current estimates are that while 1,063 have signed up, there are more than 7,000 dairy holdings in the UK and around 9,000 beef holdings (721,000 breeding animals in an average herd size of 80), so work is still to be done with the recruitment drive. Interestingly, of those signed up there is a roughly even split between dairy herds and beef herds.

In politically challenging times, we cannot ignore the fact England may soon be stood on its own. If the country fails to tackle BVD a negative impact on exports would be inevitable, with exports of live animals almost impossible as we fall behind the rest of Europe, as well as our neighbours in the UK. Do we continue to sell ourselves as the sick cow of Europe? Will our farms be able to earn their more restricted subsidies if they carry the burden of a disease that makes them inefficient?

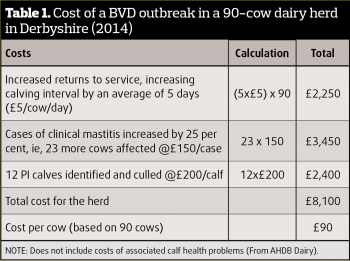

In pure monetary terms, can we afford not to eradicate BVD? The annual cost of disease to the industry is quoted as being up to £61m. While this aggregated figure is startling, it may be easier to grasp the reality in more familiar terms. It has been estimated this equates to £4,500 per year for a 100-cow beef herd, or £15,000 a year for a 130-cow milking herd (Table 1).

It has been well demonstrated eradicating PIs from farm youngstock leads to herd health improvement. In an RVC pilot eradication programme in selected farms in Somerset, calf treatments for pneumonia and scours reduced to nearly zero after all PIs were removed. This is a further benefit at a time when farms and prescribing vets are under increasing scrutiny regarding antibiotic use.

Calves that have been sick with either pneumonia or scours may never reach their full potential and the effects can be felt right up until they produce their own calves and enter their own productive cycle.

Significant psychological stress can be seen for farmers/owners and/or farm staff where there are multiple health issues. A farm with actively circulating BVD is likely to suffer poor fertility, which will go hand-in-hand with poor productivity, poor output and cash flow, as well as likely having sick and dying youngstock. In turn, this is more labour intensive and can quickly deplete the reserves, physical and mental, of most of our clients.

BVD sits in a pretty good position for the keen vet and committed farmer. We have reliable, affordable tests for antibody surveillance (exposure) and antigen hunts (infection). We have safe and effective vaccines to bolster the protection of a herd when we have biosecurity concerns.

Eradication at herd level can be achieved with commitment from farmer and vet alike in as little as two years.

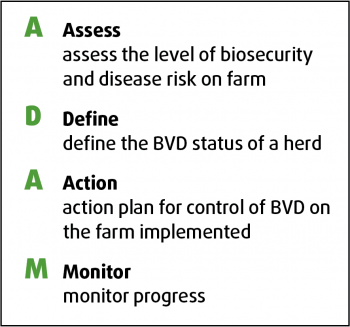

BVDFree England draws on common principles of disease control for its eradication programme (Figures 3 and 4).

Step 1 – Assess. Assess herd biosecurity and vaccination together with disease history and disease risk. Plan your objective. You should understand the risk factors on farm in the past two years. Check herd records across 18 months to 24 months, looking at fertility, herd health and milk production. Postmortem examinations of stillborn or poorly thrived calves should also be assessed.

n Antibody ELISA tests. These will give an idea of whether the group of animals has been exposed to BVDV. This can be done as a youngstock screen of nine to 15-month-old animals, five to 10 from each management group, on individual bloods (serum). Also bulk milk sampling for antibody ELISA is a quick and cheap monitoring tool, although careful interpretation is required where vaccination and previous infection needs to be considered (Booth et al, 2013).

n Antigen tests. These are where an antibody response shows exposure – the aim is to identify the source of infection.

Tag and test represents affordable and easy individual tissue PCR antigen testing the farmer can do (Figure 5). Tags can be used as management tags, or to include mandatory identification numbers. When used as whole herd surveillance, all calves (including stillborns) should be tagged as soon as possible after birth to aid identification of circulation transient infection – this is unaffected by maternally derived antibodies (MDA).

To be valid for BVDFree England purposes, an accredited laboratory needs to be used (www.bvdfree.org.uk/designated-laboratories), and this is particularly relevant for farmer-bought identity tags.

A bulk milk PCR antigen test (sensitive enough to identify a single PI in 300 milking animals) will show if virus is actively secreted into the bulk tank. This is a useful and inexpensive test, but it should be remembered it offers only a snapshot of those cows contributing on a particular day. Furthermore, false positives may occur with modified live vaccination within four weeks of vaccination.

Any individual viraemic on a first sample should, strictly speaking, be retested three weeks later, as the viraemia in a transiently infected animal only lasts 10 to 14 days. Subsequent samples testing positive will confirm the animal to be a PI.

All PI bulls produce semen infected with BVDV. Furthermore, acute infection (transient) of the bull can result in BVDV infection of the testicular tissues and semen, which, in turn, is often of poor quality and yet has the potential to spread BVDV to seronegative heifers.

It has also been demonstrated in bulls that while they may mount an immune response to transient infection-producing antibodies, those antibodies may not always be able to cross the testes barrier. In one bull, virus was continuously shed in the semen between seven to 22 months of age. Normal blood screening techniques would have shown this bull to have been immune and not shedding, although it would have posed serious risk to naive heifers.

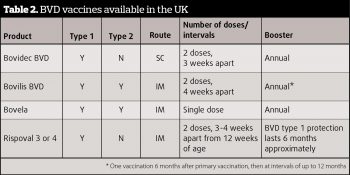

Vaccination (Table 2) has been available and widely used in the UK for more than 15 years. There was a time where it may have been perceived – by farmers and vets alike – as a cure all, without any active monitoring or PI hunting. This method of control cannot be seen as complete and PIs must be sought out in an eradication programme.

Historically, using a PI as a vaccinator animal cannot be considered an effective control policy and is outdated.

So, when should you vaccinate? Having assessed the risks, vaccination is advisable where any potential breach in biosecurity is possible. Vaccination offers cost-effective protection of the dam, thereby eliminating the production of PIs and propagation of disease within the herd.

As for all BVD vaccines, the aim is for all breeding stock to have completed a primary course two to three weeks prior to service, to ensure full fetal protection, eliminating the risk of the dam producing a PI fetus.

Strict adherence to manufacturer recommendations for storage, timing and method of delivery is critical for robust protection (Figure 6).

Failures of the vaccine to halt spread of disease have been due to incorrect timing or failure to correctly follow the primary course of two vaccines. The more recent introduction of a one-shot primary course offers protection against both types 1 and 2.

Note that while the main aim of vaccination is to halt production of future PIs on the farm, where active infection exists then vaccination of the calves to effect protection form BVD type 1 aims to reduce the immune suppressive effect and reduce virus shedding in that population.

It is clear to see from Europe that BVD eradication schemes can be successful. While BVDFree England has been launched as a voluntary initiative, a statutory requirement for all holdings to comply should follow. It is essential vets and farmers work together to achieve success here. There can be nothing more rewarding than improving overall herd health and providing a transparent market for trading animals – in one disease at least.

CASE STUDY 1

100 cow suckler unit, three younger cows aborted

BVD tag and test was initiated last year, there is no vaccination. All calves born last year tested negative.

Farmer does regularly buy in cattle, although they are kept separately. Spread of infection is quite possible from fomites from these stores to the suckler herd.

The last abortion was submitted for pathological investigation, which revealed BVDV and a pure bacterial growth from the stomach contents. Whichever infection is deemed to have caused the abortion this calf was born as a BVDV-positive animal and posed significant risk for infection to animals around it.

Tips to improve management included improved biosecurity, managing the two groups and, for the risk involved, a recommendation to tag and test any bought-in animals. It would also be prudent to vaccinate all breeding stock, including bulls.

CASE STUDY 2

390 cow dairy unit

Presenting problem fresh cow issues, retained placentas, metritis, higher incidence mastitis, poor fertility. High numbers of still births and calf scours and pneumonia.

Vaccinating breeding animals for BVD for seven years. No PI hunt had occurred.

Start tag and testing calves at birth or as soon after as possible, all stillborns tested. Forty PIs found in a six-month period. Of the stillborns tested, 90 per cent were PIs. Youngstock tag/tested revealing a further two positives.

Dams of PIs were then blood tested, all returned negative.

Decision made to vaccinate all animals on farm over three months old at annual TB test. Continue to tag and test calves born.

With removal of these PIs, herd performance has increased. Yields have increased from 25 litres to 32 litres, fertility has improved from a conception rate of 28 per cent to 48 per cent, and serves per conception lowered from 3.2 to 2.1. Calf health has improved dramatically, with calf treatments reducing to almost zero.