26 Aug 2019

Owen Atkinson takes a look at research into advancements in understanding this condition to help vets support clients.

Figure 1. Good foot health is vital for cows to express normal behaviour and produce milk efficiently. For example, in this herd with low lameness prevalence, cows average more than eight separate feeding bouts per day, heat expression is excellent and visits to the robot are unimpeded.

I recently bumped into an old farm client of mine, who asked me: “What’s new, Owen? Have you solved lameness yet?”

Cue my enthusiastic launch into some exciting developments in lameness research. After 10 seconds, my farmer friend put his hand up to stop me: “Steady on, Owen,” he said. “I was only making polite conversation. Not everyone gets as excited as you about lame cows.”

I guess lameness is not everyone’s cup of tea, and that’s a shame because my view is if you get lameness well controlled on a dairy farm, everything else follows. Or, put another way, if you are doing a good job as a dairy farmer, you won’t get lame cows – and you will probably be profitable, happier in your job and, rightly, proud of what you do.

The same is true for vets. If we work with herds with no or very low lameness levels, we will have clients for the future and they will be good herds to work with (Figure 1). If we have a bunch of clients with a lot of lame cows… well, it’s probably time to practise our anal gland-emptying skills.

This article describes some more recent advances in understanding to help us support our dairy clients to reduce lameness.

Around 30% to 32% of all adult dairy cows are lame at any one time (Atkinson and Fisher, 2013; Griffiths et al, 2018). That equates to 560,000 lame cows in Great Britain and, therefore, in pain.

This is costing our hard-pressed dairy industry around £1,225,000 every day. Around £450 million per year. An average of £42,000 per farm per year. That is about 3p per litre.

The financial impact is made up mainly of lower yield potential, poorer fertility, higher culling rates and reduced cull values (Willshire and Bell, 2009). It is a lot of money, but the impacts on human morale, ethics of farming and animal welfare are on top of any economic effects, and are, arguably, even more important.

Farmers choose to have lame cows. This was the conclusion of an 18-month study in north-west England I was involved with a few years ago (Reaseheath Agricultural Development Academy; RADA, 2013). We were looking for the factors that marked out herds with low lameness and high lameness prevalences. We thought those factors might include whether a farm foot-bathed or how the cows were housed, or the herd yields. No such links existed. But what we did find is farmers’ attitudes correlated with their herds’ lameness prevalence.

Farmers with least lameness had three things in common:

Farmers with high lameness prevalence were more likely to think it was due to external factors, such as a bad spell of nutrition, a poor foot-trimmer or the weather.

Our job as vets is, therefore, threefold:

The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) Healthy Feet Programme is the best way to do this; it works (RADA, 2013).

The fat pad story is very exciting. Those of us who qualified before this millennium would remember the fat pad, or digital cushion, of a cow’s hoof to be some irrelevant part of the anatomy, a lump of gristle somewhere in the heel. We now know three pillows exist that run under the pedal bone and that these provide valuable protection of the corium from concussive forces (Bicalho et al, 2009; Figure 2).

Thin cows seem to have thinner fat pads. Hence, thin cows go lame (as well as lame cows go thin; Bicalho et al, 2009; Machado et al 2010; Randall et al, 2015).

This amazing finding better explains how nutrition affects lameness than any theory so far. Whereas theories have previously abounded that lameness is caused by acidosis, or “laminitis” by too much protein and so on, we now know simply that anything causing cows to be too thin is likely to lead to lameness. Specifically, claw horn disruption lesions, which include sole bruising, sole ulcer and white line disease.

Many ways exist to make a mess of things and end up with thin cows. Yes, rumen acidosis is one of them, but also consider poor transition cow management, excessive negative energy balance, concurrent disease, inappropriate (too thin) body condition scores at calving and poorly grown heifers. Stay tuned for even more exhilarating stuff to come to light here.

It is likely, but not yet proven, that genetics, breed and age can all affect fat pad thickness and other characteristics. It is also likely the consistency of the digital cushion can be altered; it probably isn’t all about thickness, but density and proportion of fat versus other connective tissue may be more important. Genomics may have a major role in the future to help select for cows with better lameness resilience, purely due to different characteristics of their digital cushions.

Once-lame cows are ever-lame cows. Different reasons exist for why this may be so, and the lesion type is important here.

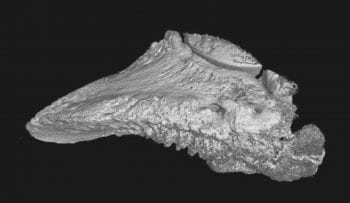

For sole bruising and sole ulcers, the inflammation can lead to bony proliferations (exostoses) on the pedal bone (Newsome et al, 2016). These can lead to greater pressure on the corium and, therefore, a vicious cycle of more inflammation, repeated sole bruising and repeated or poor-healing sole ulcers (Thomas et al, 2016).

Figure 3 shows a CT image of a pedal bone with severe exostoses. Again, this may be the tip of the iceberg because inflammatory changes are likely to alter the structure and function of the soft tissue connective tissue, too (including the digital cushion), and this could also affect the recurrence of claw horn disruption.

A novel endovascular access trial UK study (Thomas et al, 2015) showed the best treatment for claw horn disruption lesions (sole bruising and sole ulcer only in the study) was to give a therapeutic trim, plus an orthopaedic shoe (block) on the ipsilateral claw, plus a three-day course of ketoprofen. This was when comparing four treatment groups, which were:

The latter treatment was superior in terms of speed of recovery and reduced recurrence. The results led to the question of what the role of NSAIDs were in these treatments. Do cows recover better simply because they feel better, perhaps continuing to eat well and lie down with greater frequency? Or could alternative explanations exist?

A theory that has gained some currency is that NSAIDs reduce the inflammation and, therefore, the vicious cycle of connective tissue changes and reduced cushioning (Newsome et al, 2016). If this is the case, early treatment with NSAIDs would appear to be most beneficial, before the connective tissue changes have occurred.

The take-home message is we should be considering NSAIDs earlier for treatment of even mild claw horn disruption lesions, not just for the severe cases. The economic argument for doing so is sound, even with relatively small improvements in cure rate and speed of cure. Of course, if we can reduce pain too, that is also important.

Having looked at why claw horn disruption lesions may repeat after initial treatment, it is worth considering digital dermatitis (DD), too.

DD is the most prevalent lesion-causing lameness in UK herds (Archer et al, 2010). It is an infectious disease and cows with lesions are very likely to be the most important source of infection to others in the herd. However, the bacteria can be transmitted on hoof trimming equipment, for example (Sullivan et al, 2014), so biosecurity and disinfection is also important.

There is a lot still to learn about DD. Why are some cows seemingly more prone than others in the same herd? What is the role of immunity? How important are gut reservoirs of DD treponemes? What factors are involved in maintaining a healthy skin microbiome? How protective is this?

Early indications are if we can prevent heifers becoming infected before calving, cows have a much reduced chance of succumbing to DD lesions later in life.

Laven and Logue (2007) found heifers with visible lesions 12 weeks prior to calving had a significantly higher chance of developing lesions after calving. It has been suggested once a cow has developed a DD lesion, it will never truly achieve a bacteriological cure (Zinicola et al, 2015), and the disease progresses through a continual cycle of remission and relapse.

It is speculated the DD treponemes have an ability to become dormant, and – coupled with the fact they can reside deep below the surface of the skin, particularly at the bottom of hair follicles – treatment with antibiotics can only ever result in a partial and temporary clinical cure.

Once again, watch this space. The Liverpool Livestock Lameness Group has been surveying DD lesions in growing dairy heifers, and it’s through continued research we may yet learn how best to prevent DD lesions in our replacement heifers and, therefore, reduce incidence of lesions in the adult herd. More thrills to come.

This article can only really scratch the surface to give a tantalising glimpse of the world of cattle lameness research. In part, that is because I can’t keep up with it all myself; so much is going on. I have just picked out a few of the things I find particularly fascinating.

Great resources are available for cattle vets to help spread the word about lameness reduction. Many are brought together under the AHDB Healthy Feet Programme umbrella. The original Healthy Feet (Tubney) Project also still has a website resource, which is particularly useful for searching research papers.

A good starting point for getting more involved in lameness work is to become a Register of Mobility Scorers-accredited mobility scorer.

Until some better and reliable technology comes along, mobility scoring remains the essential tool for detecting lame cows early. Early detection and prompt effective treatment is a key element of the Healthy Feet Programme, and of herd-level lameness reduction (Groenevelt et al, 2014).

Next, it would be valuable to develop some more skills to help farmers reduce lameness and develop your own confidence in things such as cubicle design, footbath protocols and evaluation of trimming. You can do this by becoming a mobility mentor and learning how to implement the Healthy Feet Programme with your farm clients. Register your interest through AHDB; a new training date through the BCVA is planned for later this year.

Plenty of opportunities exist for vets when it comes to reducing cattle lameness. This is satisfying, rewarding and interesting work. Plenty of reasons exist to get more involved, too. I can think of 560,000 deserving reasons right now.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 are used with permission from the University of Nottingham and AHDB Dairy. They illustrate some of the results of the AHDB-funded research package on lameness, which has provided much-needed answers to some of our lameness questions.