18 Apr 2017

Adam Martin explains how obstetric examinations are fundamentally the same, starting with reasonable history taking and progressing through an obstetrical examination to manipulation practices.

Figure 1. Caesarean section will be inevitable in a number of cases of dystocia.

Calving the cow is a task so linked to rural veterinary practice it can make or break the reputation of many a new vet assisting at a difficult birth. Dystocia is known to have economic, welfare and production consequences for dairy cattle systems, with copious data available to show this. However, it is possibly even more acute in the beef sector. Irrespective of the causes of dystocia, obstetric examinations are fundamentally the same, starting with reasonable history taking and progressing through an obstetrical examination to manipulation practices. The author covers all these topics, plus dystocia preventive measures.

There can be little doubt dystocia compromises animal health and welfare, and is also an enormous drain on the cattle industry.

Calving the cow is also one of those tasks so explicitly linked to rural veterinary practice the reputation of many a new vet often hangs in the balance when he or she assists at a difficult calving. Despite this, much of the practical and theoretical training provided in veterinary obstetrics is from the “jewel in the crown” of UK veterinary education – EMS.

While copious data exists from dairy production systems about the economic and production consequences of dystocia, it is perhaps in the beef sector the problem is most acute. Not only do beef suckler cows experience higher levels of dystocia than their dairy equivalents, but the ramifications of dystocia are larger in this marginal sector as the calf is the entire product of the enterprise. The effects of dystocia on beef suckler farms are considerable and the consequences extend far beyond the simple economic loss caused by attendance of the calving.

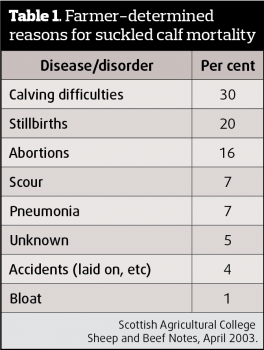

Table 1 shows the results of a farmer survey performed by the then Scottish Agricultural College (now Scotland’s Rural College), which indicates clearly deaths around calving account for around two-thirds of suckler calf mortality.

Very clear links are made between dystocia and failed passive transfer of immunity, which results in calves born by dystocia being far more likely to suffer from both pneumonia and diarrhoea, compared to those born by eutocia. Production losses associated with calf diseases are also potentially large. For example, low growth rate does not only occur in calves that have suffered from pneumonia. Low growth rates, and rescued production performance later in life, have also been described in calves that have been in a pen with animals suffering from pneumonia.

Calf diseases are largely multifactorial in origin, so removing dystocia will not remove all cases of pneumonia, but, at the population level, the number of cases will be reduced as the amount of highly susceptible animals will be reduced. Consequently, the amount of virus in a given environment is likely to be lower and, thus, more cases of pneumonia can be prevented than those that simply would have occurred in the highly susceptible calves in difficult births.

Dystocia is a predisposing factor for a number of reproductive diseases in the postpartum period, such as retained fetal membranes and uterine prolapse. Calving difficulties have also been linked to other conditions, such as left-displaced abomasum. The link between these diseases and dystocia is easily forgotten, which means the true consequences, both economically and in terms of animal welfare, are likely to be underestimated by farmer and vet alike.

Traditionally, dystocia has been classified as being either maternal or fetal in origin. Examples of maternal dystocia include milk fever or vaginal prolapse, while fetal dystocia includes abnormal position of the fetus and fetal abnormalities resulting in dystocia – for example, schistosomus reflexus. A third complication can be dystocia caused by people, which involves inappropriate intervention (often too early) in the calving process.

As is the case in nearly all classifications in clinical veterinary medicine, the categories are not necessarily mutually exclusive and some dystocia may be the result of more than one cause. In cattle, dystocia most commonly has fetal origins, abnormal presentation, position and/or posture.

Irrespective of cause, the fundamentals of an obstetrics examination and correction are the same. Initially, a reasonable history should be taken. Exactly what this includes will often depend on the relationship the attending vet has with the producer. Essential information includes details of the calf’s sire, his breed and calving history of other calves he has sired on the farm. It is also useful to know the gestation length preceding parturition.

Further information about the progression of labour should be obtained. The length of time the cow has been in labour, whether she has received assistance and what assistance she has received are all salient pieces of information to gather while assessing the calving cow.

While the history is being taken it is preferable the clinician performs a clinical inspection of the dam. If it shows signs of disease – for example, is dull and depressed – a full clinical examination may be advisable before obstetrical assistance is provided. Close attention should be paid to the cow at this point as maternal causes of dystocia, such as milk fever or toxaemia, are not uncommon. If maternal disease is identified, the clinician should make an assessment as to the importance of treatment of the dam weighed against the need to assist the birthing process.

Once the general clinical indication of the dam has been assessed – and, where appropriate, treated – attention can turn to performing obstetrical assistance. In this regard, health and safety of the farmer and attending vet should be paramount. Educating farmers to have adequate calving facilities (clean calving pen with the facility to safely secure the cow) is a priority. Calving cows in crushes should be avoided, as the potential for injury to the dam is high.

The principles of obstetric examination are straightforward. An obstetrician should be clean, patient and kind.

Hygiene is important and it is recommended the cow obstetrician washes himself or herself thoroughly before an obstetrical examination is undertaken. Gloves should also be worn. In cow cases, the protection afforded by gloves is perhaps most important for the obstetrician rather than the animal, but in other species, such as pigs and horses, the consequences of suboptimal hygiene are far more likely to negatively impact on the animals’ health. The reasons for this lie in the different placental anatomy and physiology during the postpartum period.

The obstetrician should also bear in mind parturition in cattle often takes upwards of 24 hours from its start to completion. However, second stage labour (which is characterised by myometrial and abdominal contractions) should take less than 3 hours. In certain situations, such as uterine torsion, it may be beneficial to correct the cause of the dystocia – for example, correct the torsion – before allowing the cow to calve naturally.

In cases where this strategy is not evaluated, to be optimal, one should ensure the cow is given sufficient time for the birth canal to open up before calving aids are used to forcibly extract the calf. Often this means enjoying a cup of tea before starting to pull.

The importance of lubricants should also not be underestimated. High-quality lubricants can mean the difference between a natural birth and a caesarean section. Anecdotally, in tight calving, the author has positive experience of using lubricant powder, as the powder can effectively be placed at the point it is most needed.

Bovine dystocia is mostly fetal in origin and, therefore, obstetrical manipulation is required to correct the abnormality preventing birth. By the time vets are called to a calving, herdsman have frequently tried to correct the problem.

Correct application of the aforementioned principles is important. The majority of fetal dystocia can be corrected through skilled manipulation of the fetus and perseverance. Nearly all dystocia resulting from postural defects of the calf can be manually corrected per vagium. As a general rule, calving a standing cow is far easier than calving a recumbent cow due to the increased potential space and reduced pressure on the fetus. Retropulsion of the fetus will, in almost all cases, create a larger (potentially) space to work in, which often facilitates correction.

Retropulsion of the fetus is not always an easy task when a 600kg-plus cow is trying to push the calf out. However, appropriate use of medicines can assist greatly. The most common treatment to facilitate retropulsion is epidural anaesthesia.

A variety of medicines can be used to induce epidural anaesthesia. The choice will likely depend on its speed of onset; local anaesthetics induce epidural anaesthesia very rapidly, which helps the clinician identify the anaesthetic agent has been correctly placed in the epidural space. Other considerations are the medicine’s duration of action, for which α-2 agonists are known to have an extended period

(12 to 24 hours) and, of course, withdrawal times. Ideally, after the induction of epidural anaesthesia, the cow will remain standing. While individual variation exists, keeping the epidural volume at about 7ml should provide adequate anaesthesia while not inducing recumbency in the adult cow.

In more challenging cases, the use of tocolytics, or uterine relaxants, such as clenbuterol or isoxsuprine, may be indicated in conjunction with the use of epidural anaesthesia. Both the use of epidural anaesthesia and tocolytics mean once the postural defects have been corrected, extraction of the fetus usually requires manual traction.

No doubt exists calving problems start at mating. Correct bull selection, relative to the heifers or cows he will serve, is essential. The use of breeding values for calving ease and calf size is highly recommended, particularly when breeding heifers. Heifer selection is also critical, as it is essential heifers are large enough to be bred (dairy heifers should be 55% of mature weight while beef heifers should be at least 60% of mature weight at first service). It is important once served they are fed so they grow to at least 85% of mature weight at first calving.

The body condition score (BCS) of all cows should be monitored and feed adjusted accordingly. The odd adage cows should be “fit not fat” at calving holds true. A huge body of evidence exists showing incidence of dystocia increases dramatically in over-conditioned (BCS above 3.5 of a 5-point scale) cows.

Interestingly, and in stark contrast to most people’s intuitive belief, no real evidence exists feeding cows excessively during pregnancy effects calf birth weight. This is in contrast to other species, such as sheep. However, overfeeding does lead to over-conditioned cows, which, in turn, have difficulty calving, thus the idea over-feeding can lead to dystocia is correct. It is just precious little evidence exists in the cow to suggest it has anything to do with the size of the calf born.

Adequate management of dams to prevent metabolic disease and other diseases around calving is important if dystocia is to be kept to a minimum.

Given the majority of dystocia that occurs in cows are fetal in origin – and a large number of these are due to abnormal presentation, posture or position of the fetus – these abnormalities are hard to prevent. Calves have long limbs and, unfortunately, on occasion they will be abnormally placed during parturition. Preventive measures might include ensuring stocking densities are not too high and to avoid transporting or unnecessarily driving cattle in the final stages of gestation.

The proportion of calvings requiring veterinary assistance is probably falling as the competence levels of stockmen continually improves. However, it is difficult to see them disappearing from our workload totally for many years to come. The mechanics of obstetrics are simple, but the practice still remains more of an art than a science. However, as with most things, understanding the basics well help. If you like calvings or loathe them, either way, finishing a calving with a live cow and calf leaves a certain sense of job well done that is hard to replicate.