18 Dec 2017

"The issue of personalising relationships resonated with me for the way we communicate with farm clients." – Emily Simcock in her latest Practice Notes column.

Figure 1. This ewe lost an ear and some skin from its throat due to a dog attack.

I treated myself to a new vehicle – joining the middle-aged van-owning club – and I feel old.

It doesn’t have a CD player and I have no music on other devices. This is a problem because a good singalong en route to calls is a stress buster.

However, my van does have climate control, and this step up from window ventilation will save embarrassment at junctions when singing resumes. But, for now, on the crests of south Devon’s rolling hills, where the DAB radio actually works, I’ve had a bit of music.

On BBC Radio 4, The Archers may be topical for farming and social issues, but it is pretentious tripe. However, I loved listening to Stephen Fry and Jo Brand discussing mental health, and this topic rightly remains prominent in the mainstream and veterinary media.

With farmers and vets sharing terrible statistics on suicide, I doubt many farm vets have not been affected by the death of a colleague or client. Isolation is a contributory factor in poor mental health in farming, and ambulatory farm work also has the potential to be a lonelier place than practice-based small or mixed animal jobs. We cover large areas, have remote IT solutions and may need only a couple of stock-up visits to the practice per week. Bringing the team together for regular catch-ups is something I want to ensure happens in our practice.

On a lighter note, Jo Brand had me in stitches discussing the changes in the nursing process in the 1980s, when patients stopped being referred to as “the liver in bed four”. The issue of personalising relationships resonated with me for the way we communicate with farm clients. As a student and graduate, farm calls were always booked and discussed as “Greens, Grass Farm” – for example, no first name or title. This seems a perfectly sensible way to communicate information about calls and cases. But, when I started work in New Zealand, I remember being taken aback when the boss said: “There’s a cow to see for Fred Smith.” Strangely personal and informal, I thought.

In New Zealand few good reasons exist for this. Firstly, dairy farms are usually not named, but identified by Fonterra numbers. Additionally, many practices, including that one, were set up originally by farmers as “vet clubs” and a personal bond remains.

As farm vets, we don’t have a relationship with the premises and usually not with an individual animal (except for Zombie the Jersey cow that once sent me her hoof print as a Christmas card), but with the humans inviting us to do the work. Since my New Zealand work, I always try to refer to the farm clients by their full name. I hope to encourage all the team to communicate in a more personal way and get to know a little more about their customers.

Something that affects me emotionally for both the clients and their animals was raised again by Countryfile – the sickening rise in sheep worrying. I see it and hear about it so often.

The ewe in Figure 1 was lucky to lose only its ear and some throat skin to a dog attack. It was found by the farmer and presented for prompt treatment. Rarely, it seems, are these crimes reported, because farmers do not think there will be any action or resolution from doing so.

Raising the issue on television in a frank way is helpful, but, sadly, I disagree with Tom Heap’s statement only the minority of dog owners are irresponsible. It may only be the minority who fail to prevent their dog biting sheep, but my experience in the countryside suggests many dog owners fail to maintain close control in the presence of livestock. This alone is irresponsible and the sentiment “my dog would not harm anything” is very dangerous.

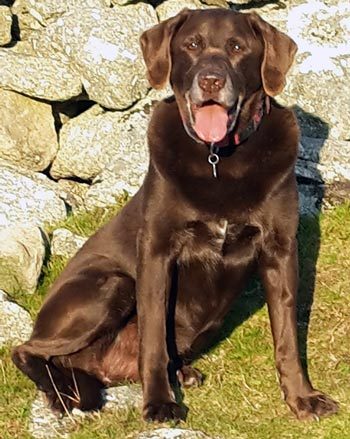

I really dislike the commonly used term in social media, including from many veterinary practices, of “furbaby”. The animal in Figure 2 is not a furbaby. He is a dog, capable of causing distress or harm to farm animals and wildlife. He is, of course, a much-loved member of my family, but he is not a furbaby.

We have an obligation to educate our clients about the responsibilities of dog ownership and I plead against the anthropomorphic labelling that suggests our pets should be treated and trained like human children.

Prevalent as ever in the media, particularly locally, is the subject of farm safety, with Devon having seen some horrendous farm fatalities. My attitude to safety changed hugely with pregnancy and parenthood. There were jobs I would not do and some I should not have done while pregnant because they were too dangerous. But, actually, if a significant danger exists of being crushed, kicked or trampled then no staff should be expected to do it, pregnant or not.

However, I felt enormous pressure when pregnant in my former practice to do more than I was happy with, and to not be a burden or inconvenience. On call one weekend, I made a really poor decision to treat a sick cow that was tied to a hurdle hung on some rotten woodwork. She was too sick to move, in respiratory distress with pungent bacterial pneumonia, but the client insisted on attempting treatment, despite me recommending euthanasia.

The cow swung her head pulling the hurdle free from the post – and into my face and shoulder. In her panic, she lurched around smacking me against the wall before I could escape. The pressure to put myself in harm’s way came from a fear of the response I would get from the client, and the practice, if I refused to treat the cow. I never want anyone else to feel that way.

I have a responsibility for the vets in my team. Last week a new farm vet was kicked handling livestock in really poor facilities. A dangerous place with fractious youngstock and a vet feeling pressure to gain a good relationship with a client by helping out.

Thankfully, it was not too serious, but was an acute reminder to me to instil a culture of dynamic risk assessing and, crucially, the confidence I will always back the vets if they refuse to work in a set up that is dangerous, whatever the reason.

Vet welfare is the most important thing. For my own well-being, perhaps it is time to get some tunes playing, instead of listening to too much serious radio.