23 Apr 2018

James Breen and Katherine Fitzgerald describe approaches to preventing and controlling disease in the herd to improve welfare and farm profitability.

Advances in technology, economic pressures and changing consumer expectations have driven changes in the UK’s dairy industry over the past two decades.

Average herd size has doubled since the mid-1990s, with cows increasingly managed in fewer, but larger, herds. The role of the dairy vet has also changed to meet the differing needs of our clients. The idyllic image of the farm vet’s daily round consisting of milk fevers, sick cows and the occasional interruption of an obstetric emergency may seem a long way from reality for most modern dairy practitioners.

However, while “cleansing“ cows and administering IV lifesaving calcium may have been replaced by interpreting disease incidence data and implementing herd level monitoring strategies, the fact remains disease incidence and prevalence remain high in many dairy herds.

We are also faced with the challenge of increasing public concern over the welfare of dairy cattle, with social media campaigns reaching wide audiences. While the mantra of “prevention is better than cure“ is clearly understood by vets and farmers alike, achieving this in practice remains a challenge.

The endemic diseases lameness and mastitis are usually ranked alongside fertility as the most costly to the dairy industry (Liang et al, 2017), making foot health and udder health a priority for many herds and their vets. Estimates of lameness in the UK dairy herd indicate a prevalence of 30% (Remnant et al, 2017), and the last national survey of clinical mastitis incidence in the UK showed a mean of around 50 cases per 100 cows/year (Bradley et al, 2007).

While cases of mastitis attended by the vet may largely be restricted to severe cases of toxic mastitis (Panel 1), working with farms to reduce incidence of mastitis represents a key opportunity to engage on improving both animal welfare and profitability.

The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) Dairy Mastitis control plan delivers a strategic, evidence-based approach to reducing mastitis in dairy herds. The plan is based around differentiating between dry period and lactation period origin, and environmental and contagious routes of infection to focus interventions at specific risk factors. This approach relies on having access to up-to-date records of mastitis treatments. Many herds make use of management software compatible with a range of veterinary analysis tools, such as Interherd or Total Vet, which facilitate recognition of patterns in the data (Figure 1).

Even in the absence of electronic records, it is a legal requirement that treatments and calvings are recorded, and can be used to establish rates of mastitis occurring during the first 30 days in milk (the target is fewer than 1 in 12 cows affected with mastitis in the first month of lactation), compared to the rate of mastitis occurring in later lactation. Herds that make the targeted changes have been demonstrated in a randomised controlled trial to reduce their incidence of clinical mastitis (Green et al, 2007).

When tackling lameness, a focus on early identification and treatment can help reduce the prevalence of disease within the herd. Regular mobility scoring and prompt identification and treatment of newly lame cows gives the best chance of achieving a cure (Thomas et al, 2015). However, vets are rarely presented with newly lame cases – rather, chronically lame cows where response to treatment is known to be poor (Thomas et al, 2016).

A longitudinal study showed the overwhelming propor

tion of the total amount of lameness in a herd was attributed to previous repeated lameness events and preventing the first case from occurring is likely to be important in avoiding escalation lameness (Randall et al, 2017). The vet – working together with the herdsman and foot trimmer to identify the causes of lameness, and establishing farm-specific strategies to reduce risk factors – is likely to be more beneficial to the herd than treating chronically lame cows and amputating digits.

While managing severe and painful cases remains part of our role, taking these as an opportunity to open the door to discussions on preventing lameness can convert firefighting to an opportunity to engage in preventive herd health.

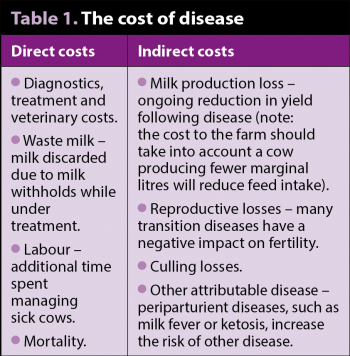

The transition period represents the highest risk of disease for dairy cattle as they undergo the metabolic challenge of adapting to lactation. A third to a half of dairy cows suffer from metabolic or infectious disease during the transition period, and approximately three-quarters of diseases in dairy cattle occur in the first month postpartum (LeBlanc, 2010). Not only does this represent a welfare issue, but a huge financial cost to the farmer that extends beyond the initial costs of treatment (Table 1). Estimates from the US priced a left-displaced abomasum at approximately £300 to £500, which clearly exceeds the veterinary costs of correction (Liang et al, 2017).

Infectious causes of periparturient disease, such as metritis, often require treatment with systemic antimicrobials. The Government has applied pressure to reduce the use of antimicrobials in food production, and minimising the use of injectable antibiotics by reducing the incidence of disease can make a big impact on herd level antimicrobial use. The AHDB and the University of Nottingham have developed a downloadable tool (https://bit.ly/2GZBRHj) that can monitor antibiotic use in herds.

Clinical disease represents the tip of the iceberg, with subclinical disease affecting even greater numbers of cattle. For example, subclinical ketosis (β-hydroxybutyrate more than 1.2mmol/L) has been estimated at more than 40% in studies repeatedly testing cows in early lactation (McArt et al, 2012). Elevated non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) in the final week prepartum are associated with a twofold to fourfold increase in risk of retained fetal membrane (RFM), two-times increased risk of culling and 1.1kg/day lower milk production in the first four months of lactation (LeBlanc, 2010).

Reproductive performance is a key driver of dairy herd profitability and the negative effects of disease in the transition period are well documented. Negative energy balance impairs reproductive performance via disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovary axis, causing reduced follicular competence and reducing response to circulating gonadotrophins.

Subclinical ketosis has been demonstrated to result in reduced expression of oestrus, poor conception rates in early lactation and extended days from calving to conception (Rutherford et al, 2016).

Strategies to identify, record and monitor the incidence of clinical disease are important to both detect and deal with problems, and identify opportunities for further investigation and intervention to limit the consequences of health problems. It is important to agree on clear definitions of diseases, such as RFM, metritis and endometritis, so the information recorded is accurate and useful. The threshold at which further investigation should occur will be farm-specific and dependent on many factors, including yield, calving pattern and expectations of the client.

Monitoring disease is, by necessity, retrospective and, hence, allows you to react to a problem rather than prevent disease. Forecasting calving patterns can allow you to forward plan by anticipating periods of pressure if space and feed access are likely to be limited.

It is widely accepted the loss of more than one body condition score point is associated with higher risk of adverse outcomes (LeBlanc, 2010). Regular body condition scoring can identify if cows are losing body condition across the transition period, but can also identify high (more than 4) or low (less than 2.5) body condition score animals that may benefit from management changes to mitigate their risk of disease.

The prevalence and, hence, cost of subclinical disease cannot be understood if it is not determined by routine screening. Prepartum NEFAs and postpartum β-hydroxybutyrate can provide useful information on transition performance, and, if carried out regularly, can help you understand the influence of changes on performance.

Prepartum urine macromineral analysis and serum calcium at the point of calving can provide information on subclinical milk fever. Sharing results of monitoring with the herd’s nutrition advisor can help provide a joined-up approach, which benefits the farm overall.

While monitoring performance is an important part of the dairy vet role, without using the information to drive change, it becomes nothing more than an additional cost to the farmer. Vets must have the knowledge and understanding of the individual farming system to use data they have collected to provide appropriate targeted advice that will lead to improvements in health and productivity.

Required changes often have a cost to the farmer – whether financial or time-based – hence the final challenge faced by vets is in understanding clients‘ motivations to effectively communicate the benefits of proposed changes.

Striving to minimise disease at the herd level has clear benefits at both the financial and animal welfare level. Vets have a clear role in monitoring disease to help clients understand the cost of it on their farms.

Engaging in disease prevention requires not only the technical skills and understanding to allow vets to identify bottlenecks and select the “low-hanging fruit“, but also excellent communication and motivation skills to create the impetus to make the required changes in management.

Nowhere is this more appropriate than in dairy practice, where “bread and butter“ cases – such as severe clinical mastitis, sole ulceration and left-displacement of the abomasum, to name but a few – showcase the opportunity to treat the sick cow, and have a way in to suggest a review of data patterns and husbandry to effect a reduction in these diseases on farm.

PANEL 1. Severe (“toxic”) mastitis

The treatment and management of a case of severe (“toxic“) clinical mastitis in a dairy cow, caused by intramammary infection with a Gram-negative pathogen (typically Escherichia coli), and characterised by recumbency shortly after calving and systemic signs of cardiovascular shock, is a classic example of the modern dairy vet role.

While the treatment approach is important, the prognosis for some cows is often poor despite aggressive therapy, and herd management is crucial to prevent these cases from occurring. Treatment approaches are still the focus of debate, with the role of antibiotics questionable, but early use of NSAIDs, IV fluid therapy and excellent nursing of great importance. Vital signs – rectal temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate mucous membranes (colour/tacky/dry) – and assessment of hydration status (for example, sunken eye, eyelid skin tent time) is important to establish prognosis, with at least half of affected cows often able to be saved.

However, as modern farm animal vets we must go further than treatment alone, consider prevention and control, and sell our expertise and time accordingly. Toxic mastitis is a great example – the disease can be considered as a combination of environmental infection pressure and adequate immune function. While we are able to focus on the latter as more tools become available, such as mastitis vaccination (Bradley et al, 2015), the former receives little attention, despite being very important in terms of disease control.

Think about the stocking density of the close-to-calving group pictured above. How many cows can you see? The Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board‘s Dairy Mastitis Control Plan (www.mastitiscontrolplan.co.uk) research suggests these cows require at least 1.25m2 per 1,000 litres milk, so if these are cows giving 10,000 litres in a lactation they require a lot of room.

In addition, we also need to think about other factors that predispose to a large “burden“ of environmental infection – poor building ventilation, poor bedding quality/frequency and lack of adequate feed/water space allowances.

If cows this close to calving are cramped, it will lead to them queuing for resources and poor intakes – leading to inadequate immune function.

Other measures include avoiding intercurrent diseases, such as lameness, and to minimise group changes.