23 Nov 2018

James Barnett presents a selection of cases from the ruminant diagnostic caseload of Axiom Veterinary Laboratories from the spring and early summer of 2018.

Presented here are selected cases from the ruminant diagnostic caseload of Axiom Veterinary Laboratories from the spring and early summer of 2018.

Axiom provides a farm animal diagnostics service to more than 300 farm and mixed practices across the UK, and receives both clinical and pathological specimens as part of its caseload. We are grateful to our clients for the cases presented in this article.

Vitamin A deficiency is probably an under-diagnosed problem in cattle herds in this country. This spring, Axiom has diagnosed a number of cases.

Presenting signs have included:

Deficiency is likely to be a consequence of poorer quality forage due to last year’s poor weather. A fire in a German factory that produced 40% to 45% of the world’s feed vitamin A precursors also resulted in precursor prices increasing from €20,000 (£17,700) to more than €250,000 (£221,200) a tonne.

As a result, livestock minerals increased by up to £200 a tonne. If levels in minerals were reduced and fed with forage with lower levels of beta carotene, the risk of vitamin A deficiency would have been increased.

Several 10-week-old “red ruby” Devon suckler calves became recumbent four days after turnout, and others exhibited weakness, muscle stiffness and ataxia, with a high stepping gait. Low glutathione peroxidase levels (14U/ml R and 15U/ml R; ref range >30U/ml R) and markedly elevated creatine kinase levels (>20,000IU/L; ref range 0IU/L to 250IU/L) in blood samples from two affected animals were consistent with white muscle disease.

Calves at risk tend to have suckled dams housed on diets low in selenium and/or vitamin E, and then undergo markedly increased levels of muscular exertion at turnout.

Long bone deformities and dwarfism were seen in six calves born to heifers. Low manganese levels were detected in four heifers and two cull cows (1.7ng/ml to 2.5ng/ml; ref range 3.5ng/ml to 20ng/ml).

Animals fed a pure silage diet during the fourth to fifth months of pregnancy are at increased risk of having congenitally affected calves and, in calf heifers, are particularly at risk due to the manganese requirements for both growth and pregnancy. If only silage is being fed, diluting it down (with straw, for example) so it contributes no more than 75% of the dry matter of the ration usually prevents long bone deformity cases.

Regarding bovine mastitis, as well as the usual suspects, a number of unusual isolates have been cultured this quarter.

Usually a commensal in the oral cavity and upper respiratory tract, Pasteurella multocida haematogenous spread to the udder may occur and suckling calves also may be a source of infection; cows with teat injuries are at higher risk. Cow-to-cow spread is suspected to occur, so it is advised affected cows are removed from the herd as usually poor response to treatment occurs.

Streptococcus canis is a rarely reported cause of subclinical mastitis. Cow-to-cow transmission occurs and a small number of herd outbreaks have been reported in the literature – for example, Hassan et al (2005).

Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus is reported in the literature as a sporadic cause of mastitis in cattle, sheep and goats and, because of its zoonotic potential, cases are of public health significance.

Ovine mastitis: Mannheimia haemolytica is one of the two most important causes of mastitis in sheep (along with Staphylococcus aureus). Teats are colonised by bacteria living commensally in the mouths of sucking lambs. Factors that may increase the likelihood of M haemolytica then entering the gland include poor teat anatomy and sucking by several lambs – for example, when housed.

Orf was detected by PCR on scabs and Staphylococcus aureus isolated from swabs from ewes with widespread teat and udder lesions, including ulceration, crusting and pustules. This mixed infection is typically associated with facial dermatitis in lambs and, with orf, infection is frequently transferred from lambs to ewes’ teats. Mastitis, occasionally gangrenous in nature, may follow the development of teat lesions.

A large herd of dairy goats suffered a major drop in milk yield, with some animals not coming in to milk and some having udders that felt abnormal on palpation. Blood samples taken from nine affected does had moderate to high levels of antibody to caprine arthritis encephalitis (CAE) virus, potentially accounting for the significant milk drop in the herd.

Further serology across different ages and groups was suggested to investigate the herd’s status, but the farmer elected to cull the herd for meat as it was no longer profitable and it was suspected many animals were infected.

Other clinical signs of CAE include arthritis, pneumonitis, encephalitis and progressive weight loss. Transmission may occur via colostrum, milk and other body fluids, infected goats remain carriers for life and many may be asymptomatic. Control measures include culling or isolating seropositive animals and their offspring, milking infected goats last and snatch rearing kids (Matthews, 2016).

Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Montevideo was isolated from the stomach contents of one of three fetuses aborted at six to seven months gestation in a Holstein herd. This serotype has been found in soya meal and reports from Scotland have suggested scavenging wild birds – particularly seagulls – may be important vectors.

Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Dublin was isolated from the stomach contents of a fetus aborted by a Texel ewe 10 to 14 days before term. S enterica subspecies enterica serovar Dublin is one of the more common Salmonella serotypes associated with abortion in sheep and is often associated with pyrexia, malaise, scour and occasionally mortality in aborting ewes. As in cattle, carrier sheep are usually responsible for introduction of this serotype into a flock.

A six-year-old dairy cow aborted and a pure heavy growth of a yeast species was isolated from fetal stomach contents. Although the majority of fungal abortions in cattle are due to Aspergillus fumigatus, abortions associated with Candida species do occur sporadically, with the predominant pathology being a necrotising placentitis, with secondary fetal infection also seen.

Although more typically isolated from ovine fetuses, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis was isolated in pure growth from the stomach contents of an aborted bovine fetus this spring. As in sheep, it is associated with sporadic abortion in cattle, and gross lesions include necrotising placentitis, fetal pneumonia and hepatic necrosis.

Blood samples were submitted from a yearling flock in which 39 out of 150 ewes were empty at scanning. No seroconversion was detected to Chlamydophila abortus and only one sampled ewe had a high titre to Toxoplasma. However, 7 out of 8 seroconverted to border disease, raising the possibility this may have been contributing to poor fertility or early embryonic loss.

Half to three-quarters of all fetuses infected with vorder disease virus in early gestation, before onset of immunocompetence, die due to uncontrolled viral replication.

Cases of listeriosis were seen in cattle and sheep this spring, including a heifer, recumbent two weeks post calving, which, prior to euthanasia, was fitting and pyrexic (temperature 40.4°C). Sheep cases included a three-year-old ewe with severe unilateral cranial nerve deficits, salivation and depression two months after lambing, and a pre-weaned lamb.

Necrotising, suppurative encephalomyelitis on histopathology was suggestive of listerial encephalitis and, in the ewe, Listeria monocytogenes was isolated on culture of cerebellum. L monocytogenes typically enters from the oral cavity via the trigeminal nerve, and tooth eruption and loss is thought to be significant in the pathogenesis of the disease. Predisposing factors include feeding of silage with a high listerial count and floor feeding in muddy conditions.

Brain and spinal cord were submitted for histopathology from a two-day-old lamb that exhibited ataxia, weakness and recumbency prior to euthanasia. Lesions were restricted to the cerebellum, with unusual degenerative changes in Purkinje cells; possibly representing early senescence (abiotrophy); they were not consistent with border disease, congenital swayback or superficial necrotising encephalopathy secondary to in utero hypoglycaemia.

Cerebellar abiotrophy at birth is occasionally seen in Welsh mountain sheep and additional CNS material was requested if further cases occurred as, in this breed, outbreaks are often seen following introduction of new rams, raising the possibility of a genetic/inherited aetiology, although teratogenic insults are also a potential cause.

Two six-month-old housed suckler calves died after an outbreak of pneumonia. Histopathology of lung detected severe necrotising bronchointerstitial pneumonia with syncytia formation and occasional inclusions highly suggestive of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) involvement, which causes damage to the bronchiolar epithelium and necrosis of type one pneumocytes. This was confirmed when RSV antigen was detected by PCR in a sample of fresh lung (Figure 1).

One five-month-old calf died after a short bout of pneumonia. Histopathology of lung revealed severe suppurative bronchopneumonia with bronchiolitis fibrosa obliterans, indicative of historic pneumotropic viral infection.

This had predisposed to secondary bacterial pneumonia, which would have accounted for the death of this animal. Bibersteinia trehalosi was isolated in pure light growth from a swab of the tracheal bifurcation. This typically causes systemic pasteurellosis in sheep, but is reported increasingly as a cause of pasteurellosis in cattle.

Samples were received from a three-month-old lamb from a flock with approximately 8% mortality in unweaned lambs. Pasteurellosis was suspected and vaccination had been initiated.

Histopathology detected consolidation, alveolar collapse, bronchiolar epithelium attenuation, filling of bronchiolar lumen and alveolar spaces with macrophages and neutrophils, type two pneumocyte hyperplasia and peribronchiolar lymphoid aggregates. This was consistent with ovine atypical pneumonia, often associated with Mycoplasma ovipneumoniae, and the degree of bronchiolar damage evident suggested possible viral involvement – for example, parainfluenza virus three. This condition can be a particular problem in lambs housed in conditions with suboptimal ventilation.

Lung samples for histopathology were received from two thin ewes with suspected ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma. In both cases, lymphocytic and histiocytic interstitial pneumonia suggested maedi-visna was the likely infectious agent.

Grossly, lungs in sheep with maedi-visna uncomplicated by secondary bacterial infections have a uniform dense rubbery texture, appear swollen in size and weigh more than 1kg in weight. Lung colour can be variable, from red and pink through to brown and grey, and there may be hard focal to confluent areas of lesioned tissue, which can be mistaken for lesions seen with ovine pulmonary adenocarcinoma.

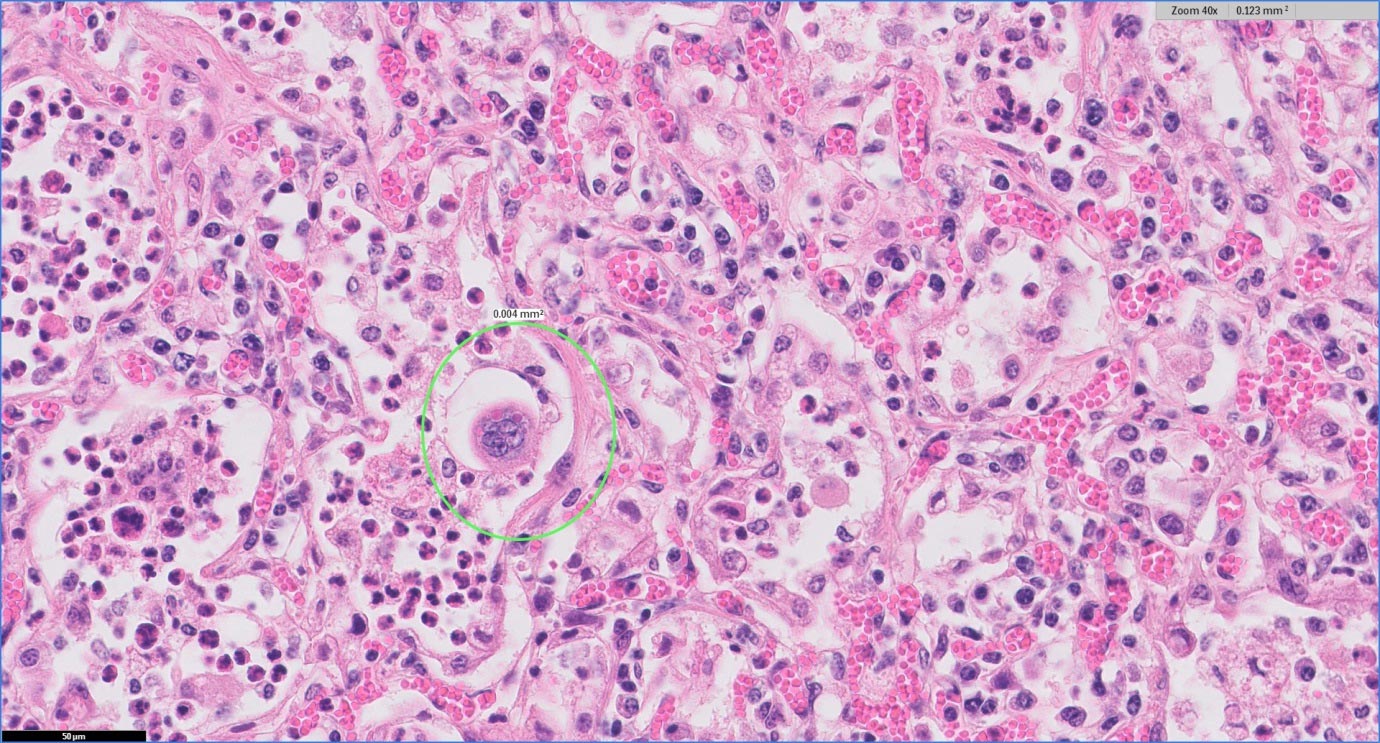

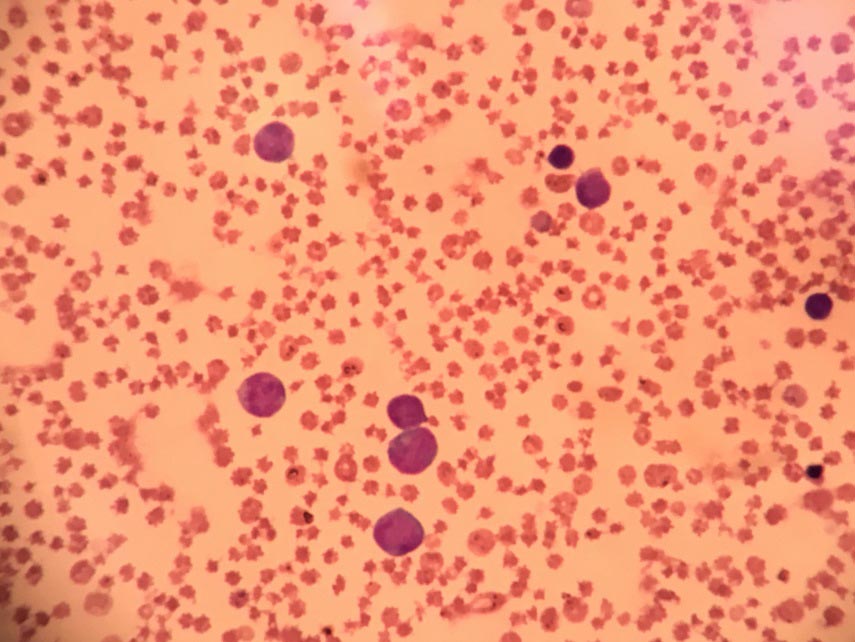

Cytology of lymph node aspirates from a Limousin calf with multifocal lymphadenopathy revealed a predominance of monomorphic medium-sized to large lymphocytes and a blood film also detected large blastic lymphoid cells in circulation. This was consistent with juvenile sporadic bovine leucosis, which, in calves less than six months old, is characterised by multiple lymph node enlargement.

The notifiable disease, enzootic bovine leukosis caused by bovine leukaemia virus is typically seen in older cattle and lymphoproliferative disease in cattle only needs to be notified to the APHA in animals more than two years old. Calves with sporadic leucosis typically exhibit weight loss, lethargy and weakness, and usually die two to eight weeks after onset of clinical signs (Figure 2).

Two cases of Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection were seen in cattle this summer. The first was a recently calved five-year-old home bred cow with a two-week history of tenesmus and dry faeces distending the rectum.

A previous case of A phagocytophilum infection had been reported in the herd three years previously, when several cows exhibited milk drop, respiratory signs, lameness and mastitis. The farm did not have a known tick problem but was frequented by deer, which may explain the sporadic episodes of infection seen.

The second case was a pale, recumbent six-month-old suckler calf exhibiting lethargy and tachycardia; the calf had been moved on to extensive grazing on moorland two months earlier. In both cases, numerous intracellular parasites consistent with Anaplasma species were seen in leucocytes. As in sheep, the tick, Ixodes ricinus is responsible for disease transmission and signs are often associated with concurrent infection due to immunosuppression.