30 Oct 2017

Chris Palgrave, Pernille Jorgensen and David Harwood discuss the inception of a network of veterinary investigation centres, plus its evolution of aims and objectives.

Postmortem examination (PME) of livestock, and the information it generates, is an important part of a farm animal health programme. This article explores how a national network of veterinary investigation centres (VICs) was set up, and how the service has evolved as its aims changed over time.

Livestock keepers and their vets are the obvious beneficiaries, but underpinning this is a continuing need to ensure the UK has a robust system in place to protect the consumer (and the taxpayer) from any future animal-related public health risk, such as BSE. Each PME is, in essence, a fragment of information that when combined with other such fragments is able to build up a valuable overview of what is a dynamic and ever-changing UK disease status.

In 1894, in response to a severe swine fever outbreak, the first national veterinary laboratory was established in a small basement room at Whitehall. This was the forerunner to the Central Veterinary Laboratory, which has been on its site in Weybridge since 1917.

Later, in 1922, the first network of veterinary laboratories was developed, operating in existing agricultural colleges. This gradually evolved into a national network of VICs established across England and Wales, providing both an important diagnostic service to vets and farmers, and a valuable source of surveillance data to monitor endemic disease, as well as detect new and emerging diseases.

Over decades, this network grew to 24 VICs and played a pivotal role in identification and control of not only important farm livestock diseases, but also newly recognised conditions.

This network remained static until a series of reviews – Rayner in 1984, followed by Dalton in 1990 and, most recently, Surveillance 2014 – took place. The number of centres (now referred to as APHA VICs) was reduced significantly to six – Bury St Edmunds, Carmarthen, Penrith, Shrewsbury, Starcross and Thirsk, in addition to APHA Lasswade, which focuses on avian PMEs. This potentially left significant areas of England and Wales without a convenient local VIC, posing a challenge for farm animal diagnostics and effective disease surveillance.

Initially, an interim government-funded transportation service was put in place, collecting carcases from farms and delivering them to the nearest APHA VIC. However, since September 2014, a number of designated “third-party providers of postmortem facilities”, operating under contract to the APHA, have been providing cover to areas no longer served directly by an APHA VIC. These include the University of Surrey (Guildford), RVC (North Mymms), University of Bristol (Langford) and Wales Veterinary Science Centre (Aberystwyth).

This has been augmented by a free carcase collection service that, since January 2017, has provided coverage for all farms outside a one-hour drive time to a PME site.

All APHA VICs, together with third-party providers, contribute to the surveillance-gathering programme, which also includes the network of SAC Consulting Disease Surveillance Centres in Scotland. In addition to the official centres, a number of independent PME providers exist, including the University of Liverpool Institute of Veterinary Science, Farm Post Mortems (north-east England) and Veterinary Investigation Services (Gloucestershire), which contribute to the network through discussions and informal sharing of surveillance information.

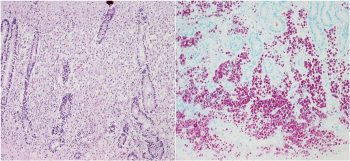

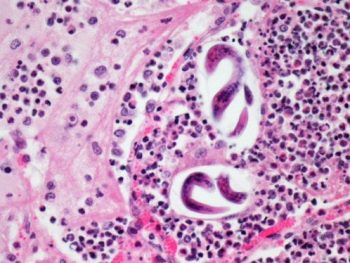

The national scanning surveillance programme is underpinned by powerful analysis of detailed data gathered by all members of the official network. At the heart of this are the Veterinary Investigation Diagnostic Analysis (VIDA) criteria, in which every diagnosis recorded is allocated a code and kept under constant review to assess trends or changes that may be important.

In addition to many diagnoses successfully reached, particular attention is paid to two additional categories – “diagnosis not reached” and “diagnosis not listed” – as it is potentially in these categories where something “new and unusual” may be identified.

A composite monthly surveillance summary appears in Veterinary Record and the analysis of VIDA data is shared through the species quarterly emerging threat reports1. Newsletters are also produced by the various providers as a means of communicating information.

However, the way that VIDA and other surveillance data is provided is rapidly evolving; for small ruminants and cattle, surveillance data can now be viewed in real time via a web-based disease surveillance dashboard2. Similar ones will be made available for other species.

One insurmountable problem is selection bias. The typical sequence of events is as follows:

Many scenarios exist where a PME can be useful:

An animal dying during a disease incident, such as pneumonia in calves, pyrexia and weight loss in an adult cow or unexpected periparturient ewe losses. It is important to ensure any carcase submitted is typical of the incident, and preferably one that has received little, if any, treatment.

To send a carcase for PME, firstly, it is important to identify the appropriate PME provider by entering the postcode of the farm into the APHA postcode finder3. This will also inform you of whether the holding is eligible for the free carcase collection service. Farms within a one-hour radius of the PME provider must arrange delivery of the carcase. Those more than one hour away are eligible for free collection.

Secondly, as the cost of the PME and any additional testing is heavily subsidised by the APHA, you must telephone the provider to make sure the carcase is eligible (see further on). If appropriate, the PME provider will instruct the haulier to collect the carcase.

The triage process assesses the time that has elapsed since death, the number of animals from a holding presenting with the same condition, the chronicity of the condition, treatment and the potential for notifiable disease. Some PME providers may still accept carcases that fail the triage process, but these are not eligible for the APHA subsidy and the cost of any additional testing may not be included in the PME price.

To maximise the chance of getting a diagnosis:

the owner’s name, address, postcode, telephone number and, if possible, County Parish Herd Holding number

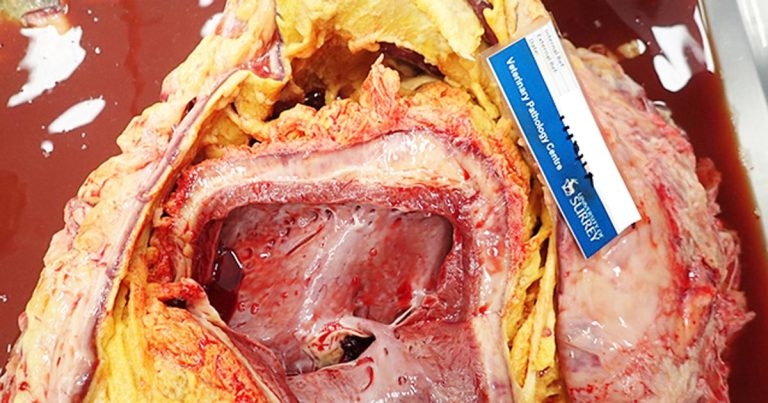

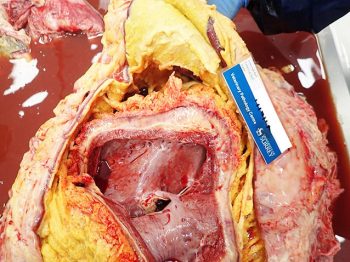

The University of Surrey is the designated third-party PME provider for south-east England, and has a modern, purpose-built Veterinary Pathology Centre that is part ofthe university’s school of veterinary medicine in Guildford4.

It is staffed by a team of technical and administrative staff, veterinary investigation officers and board-certified veterinary pathologists. On completion of the PME,APHA laboratories and third-party providers aim to provide an initial verbal and/or written report the same day or early the following day. This may be followed by the results of additional testing as they are received.

Once all further testing is complete, a final report is produced summarising the case, and provides the diagnosis (where possible) and additional comments.

While, despite all our best efforts, it is not always possible to reach a diagnosis in every case, we do achieve an 85% diagnostic rate. Where a disease is not diagnosed, this may warrant further investigation and support to take cases forward is available.

Veterinary staff at any of these designated locations are available for case discussion and sampling requirements. The APHA’s guide on sample and test selection5 provides guidance on the samples required and tests used for common disease presentations for both livestock and wildlife6.

Good images of postmortem lesions can be particularly useful. If you encounter anything that looks unusual and/or interesting, do not keep it to yourself – share it with colleagues and the wider veterinary surveillance community.

New and emerging problems have to start somewhere and it could easily be with your and/or your client.