4 May 2022

With herds getting larger and many dairy farms having professionalised, farm teams – with a specific management hierarchy – are increasingly common. Phil Elkins BVM&S, CertAVP(Cattle), MRCVS looks at how they are evolving and what they should be involved in.

In the past 20 years, the average size of dairy herds in the UK has increased from 82 to 155. However, this only tells part of the story, as many smaller herds are still in existence.

The number of herds with more than 250 cows has increased in the past 10 years from 1,204 to 1,740, with around 100 milking more than 750 cows. This increase in herd size, together with squeezing margins on many dairy units, has led to a dynamic development in the farm team.

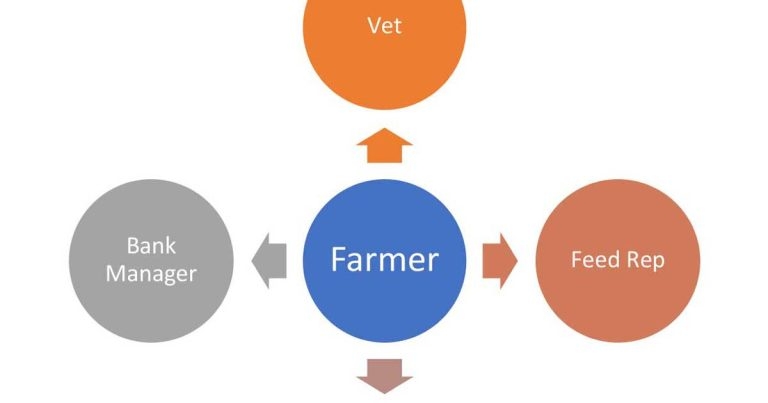

The traditional values of family farming, with minimal salaried labour provision to the farm, was the typical picture of dairy farming 20 years ago, with the farmer having a relationship with a vet, a feed salesman or nutritionist, a consultant and a bank manager, as demonstrated in Figure 1.

This model has been variably successful for the farming industry for many years, and in particular where the desired output of the herd was moderate – and the milk price relatively higher in real terms than it has been over the past five years. This model is also still very common on smaller herds, with predominantly family labour.

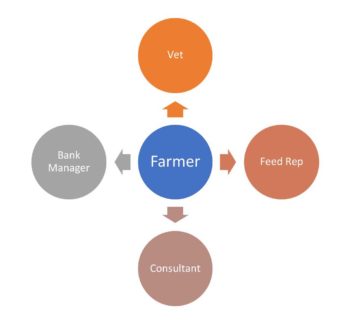

However, an increasing number of farms are increasing the complexity of their internal management structures, as well as their relationships with external organisations.

Many dairy farms are, or have already, professionalised. This includes creating a management hierarchy, increasing the responsibility and accountability of positions within the team. This may mean identifying an individual as part of a sub-team to be responsible for maintaining the standards of that sub-team. Equally, it may mean co-skilling farm staff to undertake other roles and responsibilities, including a degree of financial accountability.

Consider the example of a 900-cow, three-times-a-day milking, housed-all-year dairy herd. Under the farm owner and manager, an arable manager, a herd manager and a feed manager are responsible for maintaining the quality and presentation of stored forages. Under the herd manager is a calf manager, a night manager and a milking team manager. Under each of these are between one and five staff (some part time) reporting to them.

As each of these farms will have developed in a bespoke manner and is unique, no blueprint is in place for how a farm management hierarchy should look. In the author’s experience, other factors must also be considered, including skill set, desire and ability to recompense for the added responsibility. However, the author is yet to experience an example of a herd more than 500 cows that runs smoothly without multiple people with decision-making capability and responsibility – too many decisions need to be made on a daily basis. In fact, many smaller herds also benefit from shared responsibility.

As farms increase in size, a financial incentive usually means more management tasks can be taken on in house, as an employed member of staff is generally a lower expense and can be repurposed, if needed. This could include tasks such as foot trimming, AI and pregnancy diagnosis. This can create a sub-team of its own regarding a specific task.

For a veterinary advisor to be successful, it is important to understand how these internal farm teams work on each unit. For example, should a mobility issue arise, an investigation should include those foot trimming as well as those setting the protocols for timings of foot trims or footbaths, while considering the inherent risk factors on the farm. This may involve the farmer, herd manager and foot trimming team, but success is unlikely without buy-in from everyone.

Veterinary advisors are ideally positioned to become an integral member of external farm teams. In the traditional model, we would feed information to the farmer to be passed on to the feed salesperson or nutritionist. As vets, we have the knowledge and understanding of complex issues, as well as ready access to relevant information.

For example, if a herd is underperforming in terms of milk production, we can assess ration presentation, forage conservation, faecal consistency and contents, rumen function, external signs of rumination and milk constituents. These can then be analysed and discussed with the farm’s nutritional advisor to ensure a commonality of approach.

In the same way many farm teams have more internal members, the external teams can also have additional members. This can include the following:

For vets to remain a major part of the farm team, we need to interact and liaise with the other external members of the farm team. A significant source of advice and input to farms, as an adjunct to the farm team, is a discussion group. Discussion groups are often formally chaired by an external contact, such as a consultancy firm, with regular visits to each farm member’s farm. This offers a great opportunity for the farm to be critically assessed by peers. The author believes interactions with these discussion groups is often beneficial.

For optimum performance on farms, it is important the information is appropriately disseminated through the team structures within the farm. This must be a two-way flow of information, giving buy-in to changes, improved delivery and best chance of success. However, it is important to remember who the decision-makers are at each stage. This may mean the need for repetition.

Below is a work through for an approach to troubleshooting an issue on farm:

For this to be effective, the vet must be an integral part of the farm teams, and work closely with the farmer to facilitate the process. The aforementioned example is a fairly simple linear work through, and in reality may have many more steps involved.

An example of a more complex situation would be an increased rate of subclinical hypocalcaemia in freshly calved cows. This would involve assessing feed presentation, management of transition cows and competency of the transition diet.

Further conversations may be needed with the person mixing the feed, the herd manager and the nutritional advisor. Even if the ration is believed to be adequate, the nutritional advisor should be informed of the conversation.

It is easy to see in the example how taking a key role in the farm teams, and facilitating their performance, can get convoluted and time-consuming. A small amount of time and planning can aid this. Message groups through apps such as WhatsApp can ensure effective communications.

A number of groups can be set up for each farm, including the relevant people within sub-teams. For example, “Barn farm nutrition” group may consist of the farmer, herd manager, feed tractor driver, nutritional advisor and vet advisor. This group can then be used to share any relevant information, such as ration changes, results from monitoring transition success (such as post-calving blood ketone levels), milk production and anything else relevant.

Effectively engaging in both internal and external farm teams will take time, but it will be rewarding in terms of performance. As farms get larger, an increasing role exists for an advisor to take control of aiding the performance of these teams, and an opportunity to embed the veterinary role within the future of the herd.

This can be financially rewarding for both the farmer and the vet.

The first stage is to understand the teams within the farm, and to ensure the farmer and external team members buy into open conversation between invested (in principle, rather than financial) partners.

The author will regularly meet on farm with nutritional advisors, consultants and accountants to discuss future plans for the farm. This only comes through showing value to the farmer as a key part of his team.

With a little hard work and consideration, vet advisors can become a key part of farm teams for the future.