30 Sept 2019

Owen Atkinson considers the social aspects of antibiotic supply to farms, and steps farmers and vets can take towards responsible use.

Image: William / Adobe Stock

Antimicrobial stewardship is a hot topic. Most vets now understand the mechanics of resistance; how penicillin was discovered by accident only 70 years ago, but has changed medicine indescribably; and the cataclysmic consequences that could result from widespread resistance.

The whys and wherefores of whether this is a problem of veterinary medicine, human medicine or both are debates that can be a distraction. This is a one health issue and playing a blame game is not productive.

We are where we are with imperfect use of antibiotics on farms. The author’s experience is primarily with the dairy sector, and he has illustrated examples of poor practice he encounters in Table 1.

It is clear we are on a journey to improve the status quo. During that journey, consideration should be given to how cows’ well-being and health is safeguarded, while balancing our social responsibilities to reduce antibiotic use.

We need to consider, too, how we can best bring our farm clients along with us.

There lies the first conundrum, perhaps: do we need to bring farmers along, or are farmers already leading us? Perhaps a bit of both, depending where you look.

A Royal Association of British Dairy Farmers (RABDF)/University of Bristol survey indicated 97% of farmers regarded the antimicrobial resistance crisis as something they needed to play a part in tackling (RABDF, 2016). Yet, at the time, only 52% of the same farmers had received recommendations from their vet on reduction in antibiotic use.

Whose responsibility is it, actually, to ensure antibiotics are used responsibly on farms? The vet should be the one in charge of treatment decisions as he or she decides what medicines a farmer can use – for example, only vets can decide if a medicine can be used under the cascade. The farmer has a responsibility to follow the vet’s instructions and ensure the correct withdrawal period is followed.

But how should a farmer know what is risky for antibiotic resistance if the vet has not educated him or her? The RABDF/University of Bristol survey indicated not all vets were meeting their dairy clients’ needs for advice and information to reduce antibiotic use.

Like with climate change, perhaps, “believers” and “detractors” exist regarding the risks of antibiotic resistance. Whether we rate the risk as high or more real is likely to affect our prescribing behaviour. Similarly, farmers’ individual attitudes to risk are likely to affect how prudent their antibiotic use is.

Farmers and vets, due to the disproportionate amounts of antibiotics they are responsible for using/prescribing, will make a far greater contribution to the likelihood of antibiotic resistance developing than the average citizen; therefore, the behaviours of the few could have far-reaching effects on the many.

So, actually, our private attitudes to risk are a concern for society as a whole. Vets should be sensitive to this and encourage their farm clients to see the issue from this perspective.

We are used to hearing resistance to legislation and farm assurance guidelines – phrases such as “nanny state” and “interfering in our business”. However, the reality is that because we are in a privileged position of responsibility, farmers and vets must take that responsibility seriously. We must put the concerns of others before our own beliefs, if they are out of kilter. Even from a business perspective, putting the customer (dairy and meat consumer) first is a given.

An analogy is this: when I am a passenger in a car, I want the driver to stick to the speed limit and not send/receive text messages, because, even if he or she believes his or her driving is safe, I don’t.

Going back a step further, how do any of us assimilate all the information to make correct decisions regarding the use of antibiotics? What informs our attitude to risk? In particular, how well informed is the average farmer?

In my experience, it is very common for farmers and stockmen to totally misunderstand what antibiotic resistance means – believing, for instance, it is the animal that becomes resistant to a particular drug, not the bacteria. Furthermore, it is a rare farmer who understands how resistance occurs and, therefore, which behaviours are particularly risky. Finally, it isn’t uncommon for farmers to misunderstand which of the medicines they have on their shelves are antibiotics.

Vets’ education will necessarily ensure farmers are normally better informed, but a uniformed approach to decision-making is far from assured. Research into more than 3,000 European vets’ prescribing behaviours indicated decisions are based on a multitude of factors (De Briyne et al, 2013). “Responsible use” factors competed with “convenience factors”, “economic factors”, “society factors” (for example, owner demand) and “professional judgement factors”.

On the whole, farm animal practitioners placed marginally less emphasis on “responsible use” than their companion animal colleagues.

Significantly – although, in theory, the vet should be in charge of which antibiotics are used and in what circumstances – in practice, these decisions are often taken by farmers. This is a twofold issue:

In the UK, no reliable data is available for actual use of antibiotics on farms – both in terms of overall amounts and, certainly, in terms of specific circumstance. The VMD has challenged the different sectors to put in place systems to correct this, and the Cattle Health and Welfare Group – with BCVA representation – is working on solutions for dairy and beef farms. Progress is slow.

Records of veterinary sales data are probably more attainable than farm treatment records, but consistency of recording methods, data protection regulations and, probably, defensiveness are all stumbling blocks.

In the UK, we have a relatively trusting legislative framework when it comes to supply of medicines to farms and devising treatment protocols. That is to say, vets are trusted to prescribe and sell medicines to their clients, and not prescribe unnecessarily.

They are also trusted to devise the best treatment protocols, including cascade use where they deem it appropriate.

Meanwhile, farmers are trusted to administer treatments, as per vet instructions, and keep some prescribed medicines on the farm.

This isn’t necessarily the case elsewhere. For example, in Japan, the state vet service specifies the treatment for every condition that must always be adhered to.

In many Scandinavian countries, the vet must examine every individual animal before treatment can be given. In some instances, vets are not able to sell medicines at all, nor are farmers allowed to keep any medicines on farm. Some countries have more restrictive access to certain classes of antibiotics than in the UK.

Or, vets sit in a dispensary all day and sell to the farmer whatever they ask for. That tends to be in less developed countries and represents the opposite end of the scale.

The elephant in the room is that UK veterinary practices make a significant part of their income from the sale of medicines, including antibiotics. Therefore, it can be argued we have a direct financial incentive not to reduce antibiotic use. A Dutch report into the potential consequences of decoupling prescription from the sale of veterinary medicines concluded loss of medicine sales would significantly adversely affect the financial viability of veterinary practices, but make very little financial difference to farms (Beemer et al, 2010).

Decoupling was introduced by legislation in Denmark in 1995 and was credited by the Danish government with a 40% reduction of antibiotic use in the agricultural sector within 12 months. More than 15 years later, the number of farm vets in Denmark has not reduced, although their income has. Unfortunately, however, the amount of antibiotic use has steadily increased again and substantial illegal imports on to farms are thought to be an additional problem (Beemer at al, 2010).

In the Netherlands, since 2012, antibiotic use is monitored at species, veterinary and farm levels for cattle (De Briyne, 2016). It is also compulsory that each dairy farm has specific farm treatment plans that are devised by named individual vets each year; farmers are not allowed to deviate from these. Both individual vets and farms are benchmarked on their antibiotic use by regulators, and these measures have seen a significant reduction in antibiotic use year on year (Jan Hulsen, personal communication).

It is debatable how well the UK system functions. A more “hands-off” approach by the Government does rely on everyone playing the game and doing things right. Self-regulation is favoured in the UK. Vets have had an opportunity to shape that while tightening their act in several respects.

The VMD (2016) devised a three Rs framework to apply consistency across antibiotic stewardship plans developed across the agricultural sectors. These are:

A number of organisations in the dairy sector have some kind of stewardship plan in place. Probably, the direct-supply supermarket contracts have been leading the way on this, including a reduction in use of the highest priority critically important antimicrobials (HP-CIAs). The HP-CIAs include third-generation and fourth-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones, and are antibiotics the World Health Organization has deemed to be particularly important in safeguarding against antibiotic resistance due to their value in treating difficult infections within human medicine.

A high level of activity is taking place in the UK in a bid to contain and control antimicrobial resistance. More recently, the UK five-year antimicrobial resistance strategy (2013-18) brought together medical and veterinary bodies to work cohesively, and a UK five-year action plan for antimicrobial resistance (2019-24) was published on 24 January 2019.

These plans have been – and still are – invaluable road maps that affect the way farm vets use and prescribe antibiotics. The most recent strategy document also makes clear the progress being made, including an overall 40% reduction in antibiotic use achieved by UK livestock farming since the 2013 report was published.

In October 2017, under the auspices of the Responsible Use of Medicines in Agriculture Alliance (RUMA), voluntary targets for reducing antibiotic use in animals were agreed for eight key livestock sectors. The dairy and beef sectors, though not as high users as poultry or pig sectors on a mg/kg basis, have less robust recording systems in place. Usage targets are one thing; measuring against these targets is another.

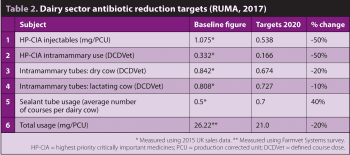

Table 2 lists the targets for the dairy sector. These targets have been based on 2015 UK sales data (from pharmaceutical wholesalers) and a voluntary veterinary practice survey conducted in 2017. In the table, mg/production corrected unit (PCU) and defined course dose (DCDVet) have been calculated using European Surveillance of Veterinary Antimicrobial Consumption methodology, which defines the PCU for a dairy cow as 425kg to normalise usage. DCDVet represents the average number of courses per dairy cow, using a standard course dose of four tubes per dry cow treatment and three tubes per lactating cow treatment.

Some more forward-thinking veterinary practices have, for several years, carried out periodic reviews and benchmarking of medicine use of their dairy clients; however, this was uncommon. Since 2018, it has been a requirement of the Red Tractor Assurance scheme (covering approximately 95% of UK dairy farms) that an antibiotic review is conducted annually with a vet. Considerable variation exists in how this is performed and recorded, but it is a good start.

The RUMA targets are a decent guide for practices to use and, of course, individual farms can be benchmarked against similar farms.

The same updated Red Tractor standards include more restricted use of HP-CIAs and a recommendation for farmers to be trained in the use of medicines. It has not yet been stipulated what this training should consist of.

In 2017, Dairy UK launched the MilkSure initiative, which was developed with the BCVA. This is a training course for farmers, delivered by their own vets, to reduce the risk of medicine residues in milk. While responsible use of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance are not the only drivers for this, they are important components.

Two short cartoon videos are available to view and share freely from the MilkSure website. These are suitable for farmers, and explain how antibiotic resistance develops and the main steps for dairy farmers to reduce the risk of this happening on their own farms.

These messages and the MilkSure training initiative are valuable resources for dairy vets:

MilkSure accreditation allows dairy producers to demonstrate they:

Owning responsibility for a problem is the first step to solving it. Progress is being made, but we still have some way to go to ensure antibiotics are always used responsibly on UK farms. To pretend otherwise is to bury one’s head in the sand.

Several individual and national initiatives exist to improve antimicrobial stewardship on farms. RUMA has led the way on this and has encouraged sharing of best practices between the different food animal species groups.

Despite some resistance, most UK vets seem reasonably happy to engage to demonstrate leadership in improving the responsible use of antibiotics. Showing strong leadership in this area is seen as helping our cause in the long run.