11 May 2022

Phil Elkins BVM&S, CertAVP(Cattle), MRCVS explains how nutritional and environmental changes can combat this increasingly common condition.

Image © littlewolf1989 / Adobe Stock

Heat stress used to be considered a disease of the tropics. However, it has become far more prevalent and for longer periods within the UK dairy population.

Many herds – in particular those housed over the summer – will have experienced some level of heat stress and associated losses in the past few years, and would benefit from some thought towards abatement strategies.

Heat stress can be defined as the sum of external forces acting on an animal that causes an increase in body temperature and evokes a physiological response – in other words, when the environment leads to clinical hyperthermia1.

Due to the heat produced through fermentation and processing of food in the rumen, cattle (and other ruminants) are more prone to the effects of heat stress than other domesticated species.

The effects of heat stress in the UK cattle population has been largely downplayed by farmers and clinicians alike.

Like many situations, this is not a static relationship, with a number of factors leading to a trend towards an increased number of cows being placed at risk of heat stress for longer periods.

These risk factors include:

Global temperature increases are well published, as is the associated increased variability observed over the past few years. It is clear to see how this will lead to an increased duration of risk period for heat stress.

Production increases are associated with a lower threshold for experiencing behavioural or production changes associated with heat stress. This is believed to be due to the increased metabolism of energy and nutrients required to facilitate increased production2.

Recognition that housing a herd during summer does not necessarily increase the risk of heat stress is important. Equally, heat stress is not limited to housed herds. However, in inadequately ventilated or shaded buildings, the risk of heat stress is far increased.

Heat stress is generally spoken about in terms of temperature humidity index (THI) – an assessment of the environmental conditions, although the situation is more complex than linking a single parameter to health or welfare parameters.

Other factors, such as airspeed, direct sunlight, diet and stocking density, will affect how the environment influences cows’ health and performance.

Thresholds have been set that are associated with physiological changes: a THI of more than 72 is associated with mild changes; 80 to 90 is associated with severe changes; a threat to life can be seen at a THI more than 90.

THIs less than 72 are generally considered to be within a cow’s thermal comfort zone – that is, they do not require an energy or behaviour change for the cow to maintain her body temperature at an appropriate level.

While meteorological models continue to demonstrate a low number of days with a mean THI of more than 72, these can hide significant periods of the day when heat stress conditions occur, and also may not represent the THI within cattle sheds.

Throughout 2021, Cargill undertook a study looking at THI at cow level in housed herds during the summer, using remote THI sensors. The results showed six consecutive days with THI of more than 80, and 25% of days where the THI was more than 70 for at least one hour. In fact, on 10% of the days, heat stress conditions were demonstrated within the sheds3.

Decreased milk production, reduced fertility and increased culling alone are estimated to cost the US dairy industry approximately £690 million per year4. Economic assessment of heat stress in UK dairy herds has not been published, but the author’s experience is that the effects will be significant, despite overt clinical disease being uncommon.

Heat stress is also not restricted to housed herds, with close data analysis indicating losses that may be attributed to heat stress in grazing herds – in particular, those with limited solar protection (shade). As for many diseases, clinical heat stress cases are, thankfully, rare, but subclinical losses can be large.

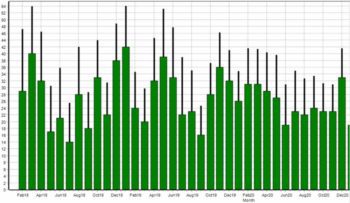

As can be seen in Figure 1, a reduction in conception rates is often seen during times of increased THI. These are often associated with reductions in milk and constituent production.

In housed herds, mechanical ventilation is often warranted to decrease both the THI and the effects of THI (through increasing airspeed), with modern fans designed to maintain optimum THI conditions through variable speeds.

Unfortunately, these require both significant capital investment and large quantities of electricity. Despite these costs, mechanical ventilation often provides a good return on investment, should cash flow allow.

A number of other measures exist that can be employed to reduce the risk of heat stress and can be used in addition to, or as an alternative to, mechanical ventilation.

When conditions tend towards heat stress, increasing the availability of drinking water both in terms of number of troughs and residual capacity/fill speed will ensure cows are able to adequately maintain their own body temperatures.

Cows will consume most of their food soon after feed presentation. Metabolising that food creates heat, so mixing and presenting the food later in the day, when it is cooler, will reduce this effect.

Similarly, when cows are grazing, giving them new breaks/moving to new pastures should be carried out in the afternoon.

Dry matter intake is reduced at times of subclinical heat stress.

Certain feedstuffs require more processing within the rumen, exacerbating the heat produced through digestion. Typically, forages – particularly those high in neutral detergent fibre such as hay or later cut silages – require more physical (chewing) and biological digestion.

Reducing forage intake levels in favour of more readily available energy, such as from protected fats or treated grains, can both lift the energy density of the diet to counteract the reduced dry matter intake and reduce the heat production from digestion. Care obviously needs to be taken to avoid inducting subacute rumen acidosis and ensure profitability of production.

Avoiding milking during the hottest times of the day is a sensible measure, with the collecting yard often exacerbating heat stress due to the relative high stocking densities.

Twice-daily milking in extreme conditions may be justified for herds that typically milk three times a day, although this will lead to consequences for milk production.

Increasing airflow does not always mean mechanical ventilation – opening up sheeted doors or removing cladding from the sides of sheds can increase the natural airflow through a shed.

However, on a still day, and in a poorly ventilated shed, this may not be effective.

Many modern sheds have large areas of skylights.

In the summer, these act like a greenhouse, increasing the THI within the shed and the direct thermal heating of animals directly beneath these.

Covering skylights, or using material such as Galebreaker to reduce the direct solar heating from open sides, can be hugely beneficial.

Equally, covering outside loafing areas to increase shade or increasing tree cover for grazed herds can help mitigate heat stress.

As mentioned previously, the collecting yard can provide a location for increased stocking and, hence, increased heat stress.

Moving smaller groups into the collecting yard at a time can limit both the stocking and duration in the collecting yard. Similarly, the collecting yards can be left open after scraping to increase the loafing area. Placing water troughs in the collecting yard is a good idea.

Sprinklers act through wetting the skin/hide, increasing the evaporative heat losses. However, using them when ventilation is not adequate will increase the humidity within a shed, exacerbating the issue.

Careful thought must be given to potential negative effects before using sprinklers.

In conclusion, heat stress occurs more frequently now in the UK, with significant effects on fertility and milk yield, and dead cows occurring in extremis.

A number of measures can be employed in both housed and grazing herds to mitigate the risks of heat stress, and protect cows from subclinical effects.