13 Aug 2024

Owen Atkinson explores how data can be used by vets for reviewing and forecasting on dairy farms.

Being asked to write about herd health planning is a triggering event for me. It was an essay question in my BVSc finals exam (1994), my RCVS Certificate exam (1997) and my RCVS Diploma exam (2013). It does not help matters that I failed one of those.

So, forgive me as I splutter my way through this article with sweaty palms and a racing heartbeat. Forgive me, too, for focusing on dairy herds – that’s what I know best – but most of what is discussed here is perfectly applicable to other production animals.

Herd health planning is not a new subject, and it’s fair to say we haven’t cracked it yet; although progress is palpable, we farm vets probably still spend far too much time treating disease and not enough time preventing it.

A simple logic exists for why this is the case: we are providers of a service that must be paid for, and farmers often choose to spend their money with us on crisis management or doing tangible jobs, such as pregnancy testing, getting cows back in calf and getting them through their next imminent farm assurance inspection or TB test, as opposed to planning.

That’s not to say they necessarily don’t see the benefit of planning for health – it’s just that life gets in the way, and it might be seen as an avoidable expense.

Time isn’t a problem for just farmers: most of us get so busy with our day-to-day lives that it can be difficult to prioritise important stuff that would ultimately make more of a difference.

Stephen Covey, in his book, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, points out that many of us spend too much time on tasks that are “urgent and important” – see the orange square in Figure 1. In other words, staving off emergencies. For dairy farmers, this includes firefighting to treat already sick animals.

Covey’s solution is to prioritise work and actions that are “important, but not urgent” – see the green square in Figure 1.

For dairy herd health, this means strategic health management and giving priority to preventive measures. In other words, herd health planning. Although this is hard to do on any given day, and with tight budgets, it is the only way to make progress towards goals, rather than being entirely reactive and at the whim of misfortune.

For herd health planning to be successful, a farmer must want to do it and a vet must have the resources, skills and inclination to deliver. Nevertheless, some pump priming by Government can make a difference.

The Animal Health and Welfare Pathway (AHWP) in England, and the Animal Health Improvement Cycle in Wales, are two examples where good, solid financial support is being offered for vets to set aside time and effort for herd health planning.

Under the AHWP, since February 2023 funding has been available for farmers for an annual vet visit to conduct an annual health and welfare review. By April 2024, more than 2,500 farmers had completed their review and been paid, with a further 2,500 in the pipeline.

Applying takes two minutes and claiming the funding takes three minutes once the review is complete. It is reasonably flexible; although, some initial priorities exist meaning that BVD testing must be part of the review. It is probably a no-brainer and it will hopefully incentivise more vet practices to reconsider how they go about herd health planning.

My own view is that for the vast majority of dairy herds, the funded two hours or so won’t be long enough, but no reason exists as for why vets should limit themselves to this and not charge their clients for the valuable extra time that might be involved to do a more thorough job.

While some excellent frameworks exist for targeted health planning in specific areas – for example, Milksure for more efficient use of veterinary medicines, the Healthy Feet Programme for reducing lameness, Action Group on Johne’s for managing Johne’s disease and the Mastitis Control Plan for improving udder health – it is still very useful to conduct an overarching review of health, welfare and performance at least once a year.

Completing a Red Tractor veterinary review can provide some framework for this, but I prefer a slightly more in-depth approach, which can then be used to facilitate the farm team to identify their own strengths and weaknesses, and to choose the improvement points they would like to pursue.

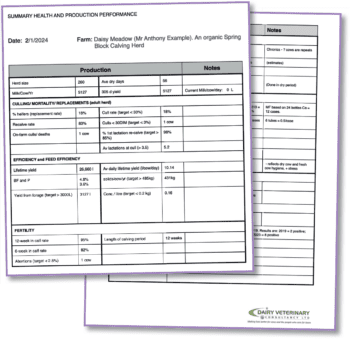

Figure 2 shows a data template that can easily be adapted, completed for an example herd, which is a spring block-calving organic herd.

A similar template for an all year round calving herd may contain slightly different parameters – especially for fertility – and, of course, the targets in some areas would be different, too.

The point is, developing a method of presenting a short summary of overall performance in the key areas is a very valuable part of herd health planning. Over-facing a farmer with too much detail or information will defeat the object, and not help with engagement.

Panel 1 provides some tips for how such a framework might work in practice with a clear eye on farmer engagement.

We all work in slightly different ways, but I tend to have a modus operandi that works well for me and, I think, most farmers. It goes something like this:

1. Before the data review visit, I’ll collate as much as possible. I ask the farm to help provide particular information so I can fill in my “farm crib sheet”, or data template – an example of which is shown in Figure 2. I use records I have to hand myself, too, such as medicine sales over the past year. I might print some things for the visit (for example, graphs), but only if I think they may be useful in our discussions on the farm. All together, this preparation might typically take three to four hours, depending on the complexity of the farm and the ease of data availability.

2. On the crib sheet, I highlight the areas that are below target, so I know before I visit where the farmer might benefit from some focus.

3. I visit the farm, pre-arranged specifically for this purpose. I avoid “tacking on” to other visits such as routine fertility visits, and I make it very clear that this visit is not for any “while you’re here” jobs.

4. The visit itself consists primarily of a farm walk with the owner, herds-person and other key people. We walk around, seeing all dairy stock. I ask lots of questions as we go. I try to “come from a place of curiosity” (that is, be nosey) to find out why they do what they do. We discuss lots while we walk, but I ensure I do less than 50 per cent of the talking. The walk and discussion takes around 1.5 to 2 hours usually. Sometimes, I need to move things on a bit, as it’s not unusual to go down rabbit holes of distracting and unhelpful topics of conversation (for example, moans about TB, milk price, vegans, Government and so forth).

5. We return to the farm office or kitchen. Over a brew, I use my “farm crib sheet” to ensure we’ve covered all the areas we need to; everyone has a copy. We discuss areas we may not have already covered during the walk. This takes another 30 minutes or so. I never pull out my computer.

6. Towards the end, I ask the farmer what their “take-homes” are. I ask them to list them and what their next steps are. Occasionally, if I think they’ve missed something I consider too important to ignore, I might prompt them.

7. I then conclude with my thoughts (but only five minutes maximum). Firstly, I list the positive things; the things they should be proud of (three minutes). Then I check the priorities for actions/improvement points (two minutes) – this helps me check I’ve understood what the farmer has told me and their take on things. The overall visit is usually two to three hours.

8. Once I have left the farm, I pull into a lay-by and scribble the main points before I forget them. I try not to write when I am on the farm, because I like to give my full attention to what the farmer or herds-person is saying.

9. I summarise the main points in a very short, typed report (preferably one side of A4, 500 words, or three sides maximum for complex farms). I ensure I include the good areas of performance, too, then send this to everyone involved.

10. I always follow up. This is one of the most difficult parts, but checking in to see how the visit and discussions landed can be very rewarding, too. Who knew so many farmers actually enjoy herd health planning?

Speaking with colleagues who work more with beef and sheep clients, I recognise that the dairy vet may be very fortunate in the amount of data we have available to us. An alternative view is that we are very unfortunate in the overwhelming amount of data we have available to us.

My experience is that many dairy farms are nowadays awash with data, whether that be from parlour software, milk recording, costings reports, genetic evaluations, lab results, medicine records, fertility and health recording software, online foot trimmer records, automated mobility records, activity meter records, rumination records or simply (very likely) reams of paper records.

Whereas in times past I involved myself with collating health and fertility records for dairy clients firstly using Daisy, and subsequently Interherd as a bureau system at the vet practice, I would now much prefer to encourage the farm to keep its own computerised records, and gain access when required. It has become a significant challenge, though, to keep abreast of all the different software solutions that farmers use, as well as widening the breadth of information a farm vet would normally avail themselves with.

To fill in a template shown in Figure 2, the following data sources may be used:

The old saying “rubbish in, rubbish out” is as true now as it has ever been. To that end, sense checking data is always essential, and keeping a degree of scepticism wherever the data may be unreliable is recommended.

Common examples where reliable and first-hand data are usually available would include using mastitis tube sales alongside recorded mastitis cases, using a Register of Mobility Scorers-accredited mobility score (preferably by a trusted colleague) for lameness prevalence, using actual milk sales instead of milk recording data and using British Cattle Movement Service data to compare calf registrations against the number of recorded calvings to check perinatal mortality.

The template in Figure 2 exemplifies some key performance indicators (KPIs) that are useful in a block-calving herd. It is important to find the KPIs relevant to the particular farm, which can be worked out reasonably easily.

Setting up which KPIs to measure is one of the first tasks for a vet during herd health planning, and this can create the framework around which all of the other preventive and advisory work can then revolve.

Good KPIs are ones where the information is easy to obtain, up to date, relevant, and gives the vet and their client useful information, which can be acted on quickly. A constant discussion among dairy vets is what the best health KPIs are, as each have their pros and cons.

The main point is that KPIs must be farm specific, and it is an important role of the farm vet to help farmers work out what theirs should be and how to keep the necessary information to monitor them.

Setting targets is a further challenge. Targets are sometimes what the best 10% or 25% of farms achieve, but collecting accurate data in a consistent way is not easy, and it is surprising how little quality aggregate data is available for most parameters.

“Herd health planning is the cornerstone to bringing value to farms through veterinary involvement.”

Each January, the Veterinary Epidemiology and Economics Research Unit at the University of Reading publishes KPIs for the UK national dairy herd, based on 500 Holstein/Friesian NMR-recorded herds, and it is a very useful resource.

Even so, it is difficult to compare herds like for like, given the UK has a very diverse dairy sector (spring block, autumn block, all-year calving, housed, grazed, hybrid, organic, conventional, Holstein; Jersey, cross-breed and so on).

Targets can be twofold: firstly, a realistically achievable level to aspire towards (that is, achieved by the top performers already) and secondly, a baseline below which actions must be taken to avoid further severe economic consequences (that is, an intervention level). Where possible, both should be decided on.

If a KPI target is not being met, by itself it is very unlikely to indicate the reason why; for example, if the mastitis rate has gone up, the data must be investigated more carefully to find the reason why.

Which cows are infected? What has been the mastitis rate in the first 30 days of lactation (target less than 1 out of 12)? What is the repeat rate (target less than 25%)? What pathogens are involved? And so forth. Only by recording details of each event can this be done.

By working with farm clients, a vet can decide how much data to record and how it can be best recorded so analysing it properly can be done with ease. Certainly, computerised records are very valuable here – especially for larger herds.

A further consideration with KPIs within herd health planning is to select some measurements which are somewhat predictive, or “early warning systems”. The vast majority of information provides feedback.

As examples, an annual cull rate reflects what happened last year; monthly herd yield is what happened last month. Some feedback information relates to events that happened a long time ago: for example, calving interval is calculated for all cows that last calved and includes events from the lactation previous to that. This might relate to fertility performance from two or more years ago; it has a long lag time.

Feedback is useful, as it might not be possible to shut the stable door after the horse has bolted, but it might at least be possible to prevent the next horse doing the same. Most farms, in reality, perform very similarly on any particular metric year on year; even if a farmer might claim they simply had a bit of bad luck last year.

In this way, even very retrospective data is useful during herd health planning to help the farmer identify their strengths and their weaker areas.

On a day to day basis, however, the best feedback is information that is available as quickly as possible after an event (a short lag). As examples, the percentage of cows pregnant by 100 days in milk, or a rolling pregnancy rate, are more valuable fertility indicators than calving interval to make time-critical improvements.

Some information might predict how things are going to evolve. These are called feed-forwards KPIs and are especially useful. While few indicators provide feed-forwards information, some do exist.

An example would be rumen fill scoring of pre-calving cows. Pre-calvers should always have as high a dry matter intake (DMI) as possible and, when it falls, post-calving problems are likely to be higher. Pre-calvers should have a rumen fill score of four or five, indicating good DMI.

Weekly rumen fill scoring of the pre-calver group can detect early problems such as forage spoilage, conflicts at the feed barrier or dirty drinking water. This information can be used to pre-empt post-calving problems, such as displaced abomasa or ketosis.

A second example is individual somatic cell count (SCC) data patterns. When monthly milk recordings are analysed, early predictors of a herd SCC rise can be used, such as the percentage of the herd above 200,000 (target less than 15%), the percentage of fresh calvers above 200,000 at first recording (target less than 10%), or the number of newly infected (risen to more than 200,000 since last recording)/number cured (gone to less than 200,000 since last recording; sometimes known as “net transmission index”, target less than 1). Several pieces of software can do this analysis very quickly and routinely.

While an annual health and performance review should always comprise one part of herd health planning, an additional aim should be to develop ongoing monitoring systems which answer performance questions as quickly as possible.

Herd health planning is the cornerstone to bringing value to farms through veterinary involvement. An increasing demand exists for this work by an increasingly business-focused farmer demographic, and farm vets might wish to set aside time to ensure they have the focus, skills and resources to deliver it without it becoming a “tick-box” exercise that no one values.

Some tips that might help are:

For farm vets interested in developing their approach to advisory work, the annual Herd Health Leadership course is a great opportunity. Scan the QR code for details.