28 Jan 2019

Katie Fitzgerald describes how developing a relationship with farmer clients helps progress their business and animal health and welfare.

Image: © Production Perig / Adobe Stock

The aim for most farm animal practitioners is to improve the health and welfare of animals under their care while also increasing productivity and efficiency for their clients’ businesses. However, to achieve this, vets must not only identify the bottlenecks that limit health and productivity, but also find solutions and work with their clients to action the necessary changes.

Through undergraduate training, further CPD and postgraduate qualifications, vets are well-equipped to make accurate diagnoses and offer solutions. Clinicians are also increasingly fuelled with information about farming clients, particularly in the dairy sector, where data capture is becoming more advanced and analysis tools to help vets make accurate diagnoses are increasingly sophisticated.

However, motivating your clients to implement changes on farm can often be the most challenging element of achieving improvements in health, welfare and productivity. Developing good professional relationships with farm animal clients is key to understanding their motivations and enabling change.

The relationship between vet and farmer is often developed over time through regular visits and overcoming shared challenges. The ability to develop these long-standing relationships is often identified as a reason vets pursue a career in farm practice over other areas of veterinary medicine (Atkinson, 2010); however, this relationship has evolved over recent years.

A proactive herd health approach and focus on advisory work are increasingly part of the vet’s role on farm and are identified in a report (Lowe, 2009) as areas that should be embraced. This area of work is not protected by the Veterinary Surgeons Act and, hence, vets must compete with other advisors in an increasingly competitive market (Atkinson, 2010). To make progress in these areas, vets need to be skilled in communication and motivating change, and be able to demonstrate their value alongside other advisors.

To effectively deliver the animal health changes they strive for, vets should not only update their skills and knowledge in advancements in veterinary medicine, but also seek to improve their skills in communication, developing professional relationships and facilitating change. The relationship between clinician and patient has been modelled in many aspects of both human and veterinary medicine.

You phase. The farmer is heavily reliant on the vet, who is seen as person of respect and trust.

I phase. The farmer is largely acting autonomously. The vet may have been replaced by other advisors or technicians in many roles.

We phase. The farmer and vet work in partnership – common goals are set and worked towards.

Atkinson (2010) describes one such model of the farmer-vet relationship categorised as three key areas (Panel 1). The “you phase” describes a relationship where the vet is seen as an expert and, as such, his or her advice should be followed.

In recent times, farmers have access to more advice, training and information than ever before, and, as such, some farmers working within tight financial budgets question the value of the vet in their enterprise altogether. This is described as the “I phase”, where the farmer largely acts independently of the vet.

Targeting the “we phase” – where the vet is viewed as part of the team on farm, and vet and farmer set common goals, and work together to find strategies to achieve them – is likely to be the most effective way to make improvements in animal health and welfare on the farm.

As vets we are driven by science and evidence base and communication and delivering change need not be different. The importance of communication and clinician-patient relationship, in delivering change in human health care as well as animal health, receives much research attention. Communication training has been more highly prioritised in recent years, with all the UK veterinary schools teaching the Calgary-Cambridge consultation model (Bard et al, 2017).

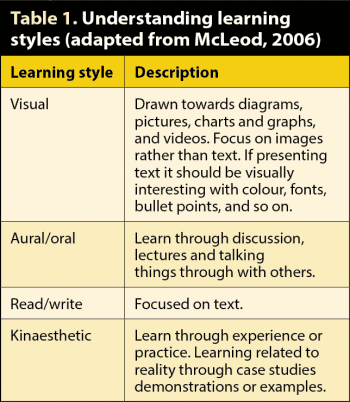

However, in practice vets often struggle to achieve the role of both scientific advisor and proactive communicator. While consultation models are useful for individual animal consultation, in advisory veterinary practice the communication skills required often go beyond this basic structure. Long-term strategies become more important and, hence, knowledge exchange and understanding farmers’ motivations, as well as learning styles, become more important (Table 1).

Lameness in dairy cattle is a good example of the mismatch between scientific understanding and change at farm level. Despite vast quantities of high-quality research immediately accessible online through a search engine, coupled with multiple CPD courses on both practical and research-focused approaches to reducing lameness, little change has been observed in the prevalence of lameness in dairy cattle over the past decade.

Recent studies of farm clinician communication styles indicate vets tend to communicate in a directive style. Vets typically set the agenda and assume clients’ values match their own, or assume a client’s values will fit a typical pattern – driven, for example, by cost or production level (Bard et al, 2017).

A shift from this “paternalistic” style (you phase) towards a relationship-centred approach (we phase) have been demonstrated to facilitate changes in behaviour (Atkinson, 2010).

Motivational interviewing is one strategy that can help facilitate change on farm, and which is receiving increased interest in farm animal practice. It is an evidence-based collaborative conversation style developed in human health care that seeks to engage clients and drive a person’s motivation to change. It utilises a set of verbal skills to cultivate empathy, collaboration and support of a client’s autonomy (Bard et al, 2017). Motivation interviewing training is available through the BCVA.

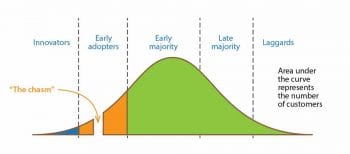

Different clients clearly have different motivators and no one-size-fits-all approach exists that will be successful. Motivators for engagement differ with farming system – for example, family farms may have different values to large-scale dairy operations (Kleen et al, 2011). Clients also have a different appetite for adopting change, as demonstrated in the technology adoption cycle (Figure 1).

As vets with regular contact with our farming clients, we are ideally placed to develop interpersonal relationships that allow us to appreciate our clients’ motivations and understand their learning styles. Combining these elements as part of a team approach is likely to yield the best results for animal health, welfare and farm productivity, as well as developing strong relations and culturing a rewarding professional relationship.

Knowledge exchange underpins most aspects of proactive herd health management, hence an understanding of different learning styles is also key in determining the most effective method to deliver information to farming clients. Multiple models of learning style include the VARK model (visual, aural/oral, read/write and kinaesthetic; Table 1).

Considering the learning style of farming team members is important in delivering information in a way that will have the biggest impact. For example, a lengthy written report following up from a mastitis investigation may not be the most appropriate method of information transfer for a client with an aural or kinaesthetic learning style.

The technology adoption life cycle (Kumbar, 2007) is a sociological model that originates from the adoption of mechanisation into agriculture and continues to be relevant to the adoption of new strategies and technologies into livestock farming. The adoption of selective dry cow therapy would be a good example.

Although significant evidence exists that blanket dry cow therapy has a negative impact on udder health, and selective dry cow therapy can reduce costs compared to double tubing, most practitioners will still be able to identify “late majority” and “laggards” who are yet to adopt the protocol. Understanding where your clients fit into this model can help you avoid frustration and fatigue.

When a new idea is presented to a farmer, he or she either chooses to innovate (to be the first user of an innovation among his or her competitors) or adopt an innovation that is already used by others, but which is still relatively new, or he or she chooses to adopt a mature technology. A farmer can also choose not to adopt anything new at all.

Several factors have been demonstrated in statistical models to increase the likelihood of a farmer being an early adopter (Diederen et al, 2003). However, at practice level, understanding your clients’ motivations and approaches can often be more valuable.

Typically, larger farms are more likely to invest in new technologies than early adopters or innovators, as they can spread the fixed costs and, thereby, reduce the risk associated with the investment. However, most practitioners will be able to identify clients with small farms who are keen to explore new ideas and large farms that approach new ideas with an “if it’s not broke” mentality.