1 Sept 2020

Axiom Veterinary Laboratories‘ latest update looks at cases of gastrointestinal and nutritional diseases from early summer 2020.

Severe fibropapillomas on the udder of a heifer where low copper levels were detected in the group (Photo courtesy of Matt Raine, Wright & Morten Vets).

Presented are selected cases from the ruminant diagnostic caseload of Axiom Veterinary Laboratories.

Axiom provides a farm animal diagnostics service to more than 300 farm and mixed practices across the UK, and receives both clinical and pathological specimens as part of its caseload. The company is grateful to clients for the cases presented in this article.

The focus for this article is gastrointestinal and nutritional disease in early summer 2020.

Escherichia coli K99 enteritis was diagnosed in both dairy herds and beef herds, with scour and deaths in young calves.

In vitro resistance often to several antibiotics was found, including various combinations of amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, cephalexin, enrofloxacin, marbofloxacin, oxytetracycline, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/S), neomycin, spectinomycin and apramycin, enrofloxacin, neomycin, apramycin, and spectinomycin.

Cryptosporidiosis was also detected in one case and rotavirus in a second case.

In at least five sheep flocks – with either suspected watery mouth or scour in lambs of younger than two days old – the E coli isolated was found to be resistant in vitro to spectinomycin. In a flock with one-day-old scouring lambs, an E coli isolated in culture was resistant in vitro to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, spectinomycin and TMP/S.

Rotavirus type B enteritis was diagnosed in two flocks. In both cases, lambs younger than two days old were reported to be affected with diarrhoea. In one flock, lambs as young as 24 hours old were affected with profuse scour.

A seven-day-old Holstein-Friesian calf went off its milk and was recumbent, with no suck reflex and toxic mucous membranes. The calf was euthanised, and postmortem examination (PME) revealed intense congestion of the small intestine and abomasum, large fibrin plaques in the peritoneal cavity and foul smelling abomasal contents.

Histopathology revealed mild abomasitis and intralesional Sarcina–like bacteria, mild acute enteritis and moderate acute serositis/peritonitis, with embedded plant debris and Sarcina-like bacteria in the peritoneal exudate raising the possibility of rupture of the abomasum or small intestine.

Sarcina are normally associated with aberrant abomasal flora and function, and necrotising and emphysematous abomasitis which is predisposed to by poor milk hygiene and feeding milk at varying concentrations and temperatures.

Coccidiosis was suspected in many cases on the basis of coccidial oocysts being detected in scouring calves older than three weeks of age, with counts occasionally exceeding 50,000opg and where no other cause was found.

Some cases were confirmed with oocyst speciation and the detection of pathogenic Eimeria species (Eimeria bovis, Eimeria zuernii and Eimeria alabamensis). The scour reported was often profuse, watery and haemorrhagic.

Many sheep flocks had suspected coccidiosis of lambs based on clinical signs and high coccidial oocyst counts that were again speciated, in some cases, with oocysts of pathogenic Eimeria species (Eimeria ovinoidalis, Eimeria crandallis) detected.

Clinical signs and, ideally, the species should be taken into account when confirming coccidiosis because very high counts can occur with non-pathogenic species. For example, in one flock lambs younger than one month old had an in-house coccidial oocyst count of 135,000opg and on speciation all were found to be non-pathogenic species.

Coccidiosis was also diagnosed in goat herds, with pathogenic Eimeria identified including Eimeria ninakohylakimovae, Eimeria arloingi, Eimeria hirci and Eimeria caprina.

In sheep flocks and goat herds, numerous cases of parasitic gastroenteritis and high strongyle egg counts in monitoring screens were seen.

An example of anthelmintic treatment failure occurred in a goat herd where faecal sampling at 14 days post-dosing found a worm egg count of 5,900 strongyle eggs per gram in a group that had received ivermectin and 900 strongyle eggs per gram in a group that had received benzimidazole.

The first case of parasitic gastroenteritis due to Nematodirus battus was diagnosed on 31 March in a sheep flock in south Wales, which is early in the year for the disease. It involved a Texel one-month-old lamb that had been found dead and had a faecal worm egg count of 300epg.

Three further cases were diagnosed in April, based on worm egg counts, but diarrhoea and deaths due to nematodirosis can occur with the larval stages before the adult egg laying worms are present. A small intestinal gut wash is, therefore, recommended on any fatal cases involving diarrhoeic lambs in spring and early summer.

Several more cases occurred in May, June and July.

Haemonchosis was suspected in several sheep flocks and goat herds where very high worm egg counts were detected. In some cases, signs of anaemia were also reported.

The diagnosis was confirmed using the egg staining technique in a small number of flocks and herds.

In one example, a faeces sample received from one of several thin, sick ewes, with high worm egg counts on in-house testing, had a strongyle egg count of 12,600epg and 88% of the eggs had positive fluorescence consistent with Haemonchus.

However, in the majority of cases, egg staining was not carried out. One example was a two-year-old thin, anaemic, lethargic Dorset Down ewe that had received monepantel one month previously.

An example of a suspected case in a goat was a three-year-old nanny that had kidded one week previously, but was lethargic, pale and thin, and had scant, loose faeces. The worm egg count was 17,800 strongyle eggs per gram.

Teladorsagiasis was confirmed in an ill thrifty two-year-old Jacob ewe with a pepsinogen level of 4.0IU/L and in a scouring goat with a pepsinogen level of 3.7IU/L that also had a low copper level (with pepsinogen levels exceeding 2.5IU/L; abomasal parasitism is likely to be associated with clinical disease).

In cattle, parasitic gastroenteritis was diagnosed in a group of three beef yearlings that had been ill thrifty since weaning and had been treated with moxidectin pour-on multiple times.

High worm egg counts were detected – in a fatal case the count was 3,300 strongyle eggs per gram. Liver selenium was also low in this animal at 0.57mg/kg dry matter (DM; reference range 0.9mg/kg to 1.75mg/kg DM) and, on histopathology, evidence existed of parasitic gastritis.

High strongyle egg counts also were detected in a several other herds, including in a number of routine screens.

Ostertagiasis was confirmed in an ill thrifty two-year-old Shorthorn heifer with profuse scour. A worm egg count in-house was negative, but a pepsinogen level of 7.2IU/L was consistent with significant abomasal parasitism.

A high pepsinogen level (6.6IU/L) was also seen in an ill thrifty Charolais cow and blood testing nine of a group of cattle – some of which were in poor condition – detected raised pepsinogen levels of up to 4.1IU/L in eight animals, suggesting ostertagiasis involvement.

A five-week-old suckled calf, which had been at grass and had died after scouring, had a worm egg count of 3,000 Toxocara vitulorum eggs per gram.

T vitulorum is more usually found in tropical and subtropical regions, although occasional cases have been reported in this country. Infection of calves usually occurs from the dam by either via the transplacental or transmammary routes.

Among the cases of fasciolosis diagnosed on coproantigen ELISA and microscopy was a one-year-old Charolais heifer with watery faeces, poor rumination and a low body temperature. Interestingly, as with many other animals, rumen fluke eggs also were found and, in this case, the possibility that larval paramphistomiasis was contributing to the clinical signs could not be ruled out.

As with cattle, several cases of fasciolosis were diagnosed in sheep, including in a flock of 160 Welsh mountain ewes where five animals had been lost over a few days.

An 11-year-old Boer goat with wasting also had evidence of fasciolosis on coproantigen testing of a faeces sample.

Parasitic gastroenteritis, liver fluke and rumen fluke infestations were detected in a two-year-old Highland finisher, which was in poor condition and scouring, and reported to have lost weight in the previous week.

In two other cases of fasciolosis, the animals were also shedding Mycobacterium paratuberculosis subspecies avium (MAP) in their faeces consistent with concurrent Johne’s disease.

Similarly, an eight-year-old Charolais bull with weight loss and profuse scour was positive for fasciolosis on coproantigen ELISA and for Johne’s on serology.

Among the many other cases of Johne’s disease diagnosed on serology and faecal PCR in cattle were:

In a group of 16 replacement heifers where a case of Johne’s disease had been confirmed – and two other deaths following chronic wasting, one of which was also a heifer – 13 of the 16 heifers in the cohort were found to have high levels of antibodies to Johne’s disease. This suggested the group either had been exposed to a very heavy challenge as young calves or had been infected in utero. It was advised that none of the group should be kept as replacements as they were all high-risk.

Johne’s disease was diagnosed in several sheep flocks, including in yearlings suffering from ill thrift in three different flocks.

It was also diagnosed in a number of goats on serology and faecal PCR.

Three cows in different herds with clinical signs suspicious of Johne’s disease were antibody negative, but positive on PCR testing for MAP. Approximately 1 in 10 clinical cases will be antibody negative, so submitting faeces as well as blood is worth considering as the faeces can be tested if the blood is negative on serology.

One infected Holstein-Friesian cow was also infected with Salmonella enterica serovar Mbandaka.

Salmonellosis was detected in several herds:

Salmonellosis and bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) virus infections were diagnosed in an unvaccinated 360-cow dairy herd. A recent episode of sudden milk drop had occurred in fresh calvers and three or four cows were pyrexic with scour or loose, pasty faeces.

The isolate was serotyped as Salmonella 6,7:-:enz15 – which is a variant of S enterica serovar Mbandaka, which is often feed-associated. A sample of milk from the bulk tank was positive for BVD virus on PCR testing.

Type D clostridial enterotoxaemia was suspected to be the case of acute scour in two milking goats after the detection of epsilon toxin in their faeces.

Duodenal infarction was identified on histopathology in a Holstein cow. The cow’s condition had been deteriorating for a month, she was inappetant, the rumen was bloated and turnover was spasmodic.

The infarction was aged at three to seven days, and the most likely cause was believed to be duodenal sigmoid flexure volvulus resulting in venous occlusion and thrombosis, although this normally has a more acute presentation. No evidence of viral involvement was present.

A number of other cases of focal duodenal necrosis have been reported in dairy cattle recently, the aetiology of which have not been established.

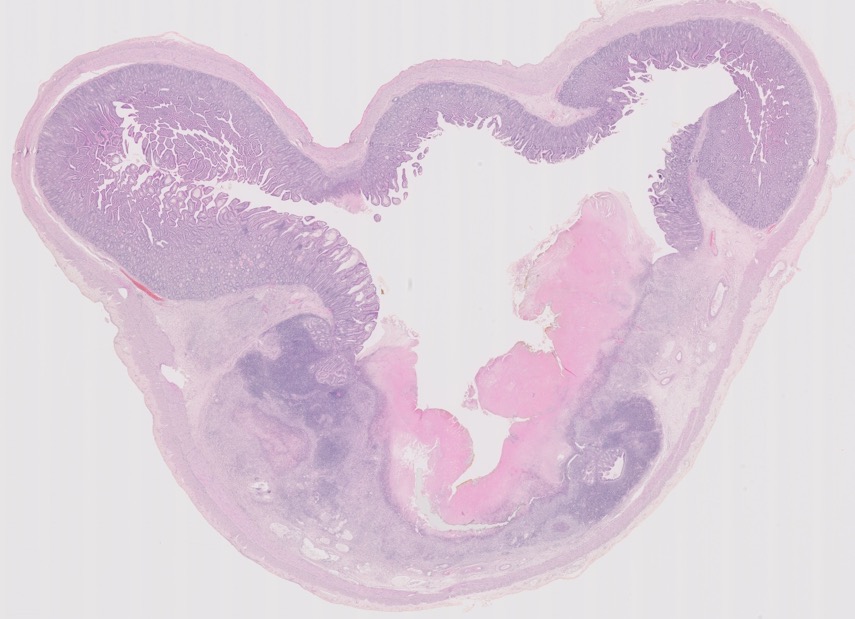

Idiopathic necrotising enteritis (INE) of beef calves was suspected to be the cause of death in three calves from different herds.

Histopathology of INE cases reveals necrotising colitis and typically only a minimal neutrophilic component exists to the enteritis. A profound neutropenia also often exists due to bone marrow depression.

However, a definitive diagnosis of the disease cannot be established on histopathology alone and it remains one of exclusion, and it is particularly important to rule out mucosal disease through BVD antigen testing.

INE is usually seen in animals between two months and four months of age, and commonly interstitial nephritis and pneumonia are also present.

Low copper levels were detected in a number of herds, often in combination with selenium deficiency.

In one example, many weak calves were born in a suckler herd and blood testing revealed low copper levels in four out of five late pregnancy cows (mean copper 6.6umol/L; reference range 9umol/L to 20umol/L), one of which also had a low glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) level consistent with low selenium status. Marginal T4 levels were also detected.

Another suckler herd was investigated after 40 out of 180 cows had calved, with 4 calves dying within minutes of birth from cows that were in good body condition. Copper levels were low in all six cows sampled, with a mean of 5.8umol/L.

Cattle in a herd with some cases of severe fibropapillomas were found to have copper levels as low as 6.2umol/L (with a mean of 8.1umol/L).

Adequate copper is necessary for an effective immune system and some studies in South America have found a benefit from copper supplementation by injection in cattle with papillomas, particularly in early cases.

Low copper levels were also detected in a number of sheep flocks and delayed swayback was the likely cause of the hindlimb ataxia affecting a three-month-old Boer goat. Plasma copper was low at 3.5umol/L (reference range 9umol/L to 25umol/L).

It was also likely to have been the cause of sudden hindlimb weakness in a two-month-old to three-month-old pygmy kid where the blood copper was also very low at 3.4umol/L. This kid was noticeably thinner than the rest.

A low copper level (3umol/L) also was seen in a two-year-old male goat with chronic scour and weight loss.

High liver copper levels were detected in dairy cows from four herds and in a five-month-old animal from a calf rearing premises.

One case highlighted why follow-up monitoring in herds that are receiving copper supplementation is worthwhile. The Friesian herd was in a historically low copper area and the cows had been receiving supplementation via their concentrates. All six of the liver samples had high copper levels – ranging from 13,200umol/kg to 26,500umol/kg DM – with a mean of 19,530umol/kg DM (reference range 314umol/kg to 7,850umol/kg DM).

In the case on the calf rearing premises, the five-month-old Aberdeen Angus calf was one of a group of poor doing calves. Moderate coccidial oocyst counts had been detected previously, and they had been fed hay, barley and molasses all winter. Liver copper was high at 20,800umol/kg DM.

Copper poisoning was also confirmed in a sheep with a markedly elevated liver copper level (74,500umol/kg DM; reference range 314umol/kg to 7,850umol/kg).

Liver concentrations above approximately 30,000umol/kg DM are potential food safety incidents and it was advised that the case be reported to the APHA. Under the Food Safety Act 1990, farmers and their advisors need to be seen to act with “due diligence” to protect the food chain.

Selenium deficiency was detected in a number of cases, including in a herd where a yearling was half the size of its herd mates. An apparently normal animal from the group was also sampled for comparison – it also had a low GSH-Px level.

Selenium deficiency was also diagnosed in a suckler herd where calves were dopey from birth with no history of dystocia.

White muscle disease due to selenium deficiency was likely to have been the cause of the clinical signs reported in some herds – one example being two three-month-old calves at grass that were stiff, had knuckling joints and one was recumbent. GSH-Px levels were very low, at 7U/ml and 6U/ml RBC (reference range greater than 30U/ml RBC).

Nutritional cardiomyopathy consistent with selenium/vitamin E deficiency was diagnosed in a two-month-old goat kid. Problems had occurred with coccidiosis on the unit, which had appeared to continue despite treatment.

The kid had loose faeces and a pale left ventricle was noted at PME. Histopathology detected occasional coccidial structures in the large intestine, but the main finding was of a severe polyphasic necrotising and mineralising cardiomyopathy.

Vitamin E deficiency was diagnosed in a number of herds – primarily in calves – with ill thrift, pica and increased mortality reported.

One calf knuckling on one hindleg was found to have a low vitamin E level and high creatine kinase level consistent with white muscle disease.

It was also identified in a Charolais cow as part of an investigation into the losses of three out of six calves born. Calves were reported to be small at birth. This cow had delivered a stillborn 25kg calf. A history of iodine deficiency existed in the herd, but no evidence existed of thyroid abnormalities on histopathology from this calf. The cow had a low level of vitamin E at 0.6umol/L (reference range 3umol/L to 18umol/l).

Vitamin E deficiency was also diagnosed in two out of five (with two more marginal) thin ewes sampled in a lowland flock.

Vitamin E and vitamin A deficiency were diagnosed in a three-week-old Holstein-Friesian calf in a herd where sporadic deaths of young calves occurred, occasionally preceded by scour and pneumonia.

Further cases of vitamin A deficiency were seen in a number of herds. In one example, two fattening bulls with sudden onset blindness had low vitamin A levels.

Animals on high concentrate ration systems are at risk from vitamin A deficiency if adequate supplementation is not provided – blindness is a recognised sign of the condition.

Low levels also were seen in two of a group of one-week-old to two-week-old calves where a quarter to half had neurological signs, including fitting, ataxia and, in some cases, stiff joints.

Vitamin A is important for good immune function and colostrum is the main source of vitamin A for newborn calves, so low levels can be due to low colostral intakes. However, it can also be due to low liver stores in the calves if the cows were deficient.

Low vitamin B12 levels consistent with cobalt deficiency were seen in a number of sheep flocks and goats. Presenting signs, where reported, including ill thrift, pruritic or dry skin, poor coat quality, alopecia and scabby ears.

In two goat herds with evidence of cobalt deficiency, two also had low copper levels – and in one case, evidence existed of parasitic gastroenteritis with worm egg counts of up to 5,800 strongyle eggs per gram detected.

Cobalt and selenium deficiencies were detected in all six, one-year-old to two-year-old Wiltshire horn sheep that had been at grass for three weeks. They were in poor condition, had nasal discharges and some were scouring. Eight deaths had occurred in five months from the original group of 46.

A case of multifactorial nutritional deficiency was seen in a group of four-month-old calves, of which one was thin and recumbent, and another was in poor body condition and scouring. The group also had gingery coats.

The mean GSH-Px level was 12U/ml RBC (reference range greater than 30U/ml RBC) and evidence existed of copper deficiency as the mean copper level was 4.4umol/L (reference range 9umol/L to 20umol/l).

One had a low vitamin E level of 1.9mg/L (reference range greater than 3mg/L), while the other calf had a normal level; however, it had been supplemented by injection four days before being blood sampled.

A three-week-old suckled calf that had been slow since birth and was dull and slow to rise, but with no other clinical signs, was found to have a low T4 level of 32nmol/L (calf reference range 84nmol/L to 283nmol/L), which is suggestive of iodine deficiency.

It was the second calf to be born in the 220-cow herd, with the first calf having died.

If cows have adequate iodine status their calves tend to be born with high T4 levels that decline over the first few months. No evidence of selenium deficiency was present in this case.

Low plasma inorganic iodine levels were also seen in a number of herds and flocks. Many were monitoring tests, but, where a history was given, signs included poor fertility, reduced lambing percentage, stillbirths and pica.

In addition to classic cases of hypocalcaemia in freshly calved dairy cows, low calcium levels were detected in dairy herds in cows in later lactation.

In one situation, a history was present of very high yielding cows experiencing milk drop in mid-lactation and often a displaced abomasum, which tended to have poor postoperative outcomes. One cow from the herd, which was about 260 days in milk, was recumbent with classic milk fever signs.

Additionally to a low calcium level, liver enzymes were massively elevated. Glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH) was 1,368U/L (reference range less than 25U/L) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) was 1,198U/L (reference range less than 35U/L). Non-esterified fatty acids was also high, raising suspicions of fatty liver disease.

The cow survived following treatment and two weeks later GLDH had returned to normal, showing the remarkable capacity for the liver to recover. GGT was still high at 229U/L. The half-life for GGT in cattle is not known, but in horses and dogs it is considered to be three days – so if this applies to cattle the GGT should also have returned to almost normal after two weeks if the cause had been removed.

The blood copper level two weeks post-recovery was at the upper end of the reference range and a fatal case in the herd had been found to have high liver copper of greater than 13,000umol/kg DM (reference range 314umol/kg to 7,850umol/kg DM). Further investigation of the herd’s copper status was to be carried out on more liver samples.

Hypocalcaemia was also detected in a number of sheep flocks. One case involved a ewe that was about two weeks to four weeks pre-lambing and had been found recumbent the day after being handled for vaccination and worming.

A heavily pregnant pygmy goat that was recumbent and showing neurological signs was also found to have hypocalcaemia.

Among the many cases of hypomagnesaemia were:

Hypomagnesaemia also was the cause of the sudden deaths of ewes in some flocks, including a flock where ewes were dying suddenly at least three weeks post-lambing.

Evidence of hypomagnesaemia was also detected in a ewe with progressive ataxia and limb weakness; 6 ewes in the 600-ewe flock had shown similar clinical signs about a month post-lambing.

A number of reports have been made this year of cattle showing signs of pica; it has also been highlighted in the farming press.

Various reasons exist for pica occurring – low phosphate levels were found in a couple of herds, one of which also had low magnesium, and another herd had evidence of selenium deficiency.

Other possible suggested causes include sodium or copper deficiency and lack of fibre. The latter could be due to lush, heavily fertilised grass or a lack of grass – for example, due to drought conditions.

Ruling out deficiencies is worthwhile in affected herds and providing fibre, such as hay or straw (molasses on the straw may encourage intakes), or buffer feeding after milking before turning back out may be worth trying.

Hypophosphataemia was also detected on blood sampling a ewe after two ewes, which had been moved on to lush pasture, became recumbent and weak after knuckling of the hindlimbs. They were still bright, alert and responsive.

Pregnancy toxaemia was diagnosed in a Hereford cow that was eight months pregnant, and showing neurological signs and ataxia. Beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) was high at 8.08mmol/L (reference range less than 1.2mmol/L) and NEFA was very high at 2,118umol/L (reference range less than 600umol/L).

Ketosis was confirmed in a dull Holstein-Friesian cow with a gallop heart rhythm and corded jugular veins, with a BHB level of 9.36mmol/L.

Ketosis and an elevated NEFA level consistent with fatty liver syndrome (1,887umol/L) was reported in a five-year-old Holstein cow with a suspected left displaced abomasum, one of a number to have suffered weight loss post-calving.

Low manganese levels were detected in seven out of eight Holstein cows in a herd with fertility issues. Two of the cows also had low vitamin A levels.

Manganese and vitamin A are both important for fertility. Low manganese levels have been associated with anoestrus and reduced conception rates, and the latter can occur with low vitamin A status.

Manganese deficiency also was diagnosed in a suckler herd with signs of pica and ill thrift.

Zinc deficiency was diagnosed in at least three pygmy goats with scaly and dry skin. One was also arthritic – and zinc deficiency has been associated with skeletal abnormalities and lameness, as well as with proliferative dermatitis in goats.

One animal was also pruritic and, as zinc-associated dermatitis is not usually pruritic, the possibility of concurrent disease could not be ruled out. In-house testing had not detected any ectoparasites.

Low zinc levels also were seen in pre-tupping samples from four out of five ewes in a flock where the lambing percentage had been down on the previous year.

An unusual case of zinc toxicity was diagnosed in a group of Holstein calves that were close to weaning.

Haematuria had been seen and the calves were reported to be slightly lethargic. Some mild pneumonia had been present in the group.

The calves had been receiving a home mixed feed for the first time, so a formulation issue was suspected.

The blood sample that was submitted was grossly haemolysed. Zinc toxicity can cause haemolytic anaemia and the diagnosis was confirmed from the high serum zinc level of 107.9umol/L (reference range 8umol/L to 24umol/L).

Due to the calves being very young, and taking into account the excretion rate of zinc, it was considered no risk existed to the food chain.

Low urea levels – suggestive of inadequate amounts of ruminal degradable protein in rations – were detected in a number of suckler herds with no other significant factors identified.

The histories were of cows that were failing to thrive, had lost weight or were weak.

Lead poisoning was confirmed in three herds.

In one case, an elevated plasma lead level (6.3umol/L) greater than that considered consistent with poisoning (greater than 1.2umol/L) was found in a one-year-old South Devon animal that was blind and had head tremors. The animals had been grazing in a field with a discarded lead battery, and one death had been reported. The blood lead level was high enough to raise a potential food chain Issue – it was advised that the case be reported to the APHA.

Follow-up testing in three more herds, following lead exposure between one year and two years previously, found the lead levels were still raised – demonstrating how long it can take for lead to be excreted from the body.

If lead levels are between 0.15umol/L and 0.48umol/L then offal has to be discarded at slaughter, which can incur a significant charge.