31 Oct 2019

Axiom Veterinary Laboratories’ latest update looks at gastrointestinal and nutritional diseases during late summer 2019 – including cases of parasitic gastroenteritis and mineral deficiency.

Image © RoyBuri / Pixabay

Presented are selected cases from the ruminant diagnostic caseload of Axiom Veterinary Laboratories.

Axiom provides a farm animal diagnostics service to more than 300 farm and mixed practices across the UK, and receives both clinical and pathological specimens as part of its caseload. The company is grateful to clients for the cases presented in this article.

The focus for this article is gastrointestinal and nutritional disease in late summer 2019.

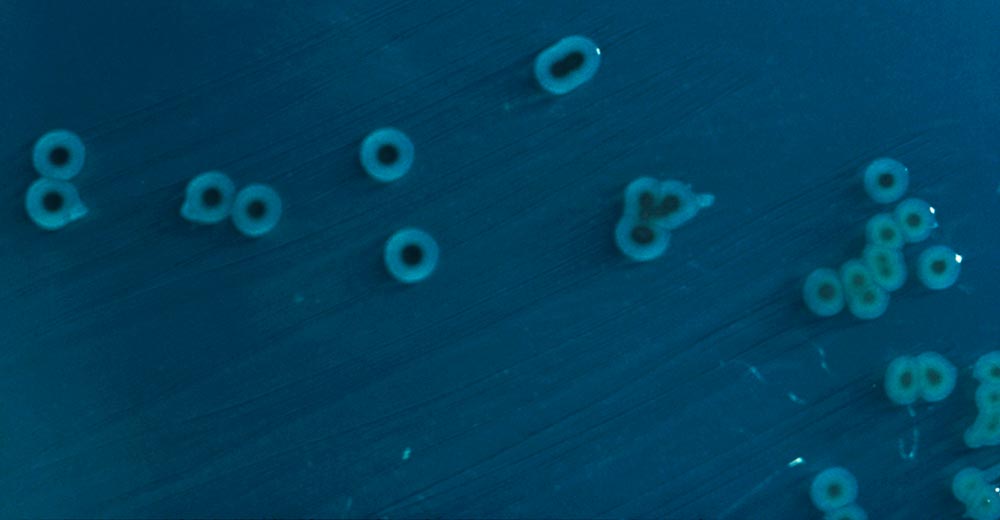

Sarcina-associated abomasitis was confirmed on histopathology in two four-day-old dairy calves that died in a 24-hour period.

On postmortem examination (PME), the abomasums were gas-filled, the walls appeared thickened and, in one, a perforated ulcer was present.

Management factors, including hygiene, are believed to play a role in the aetiology of this condition.

In a second case of abomasitis – in a 36-hour-old Friesian calf – histopathology suggested the abomasitis was probably clostridial in origin.

A variety of clostridia have been associated with emphysematous abomasitis in calves, including Clostridium perfringens, Clostridium septicum and Clostridium fallax.

A number of predisposing factors – including poor environmental hygiene, changes in milk concentration, low milk temperature and hypogammaglobulinaemia – are important in the development of this condition.

The calves were on diclazuril until the move, coccidial oocyst counts never exceeded 400opg and faeces contained no blood or mucus. One batch of calves treated with diclazuril one week after entering the new housing also succumbed.

High levels of environmental contamination were likely to have been present, despite cleaning and disinfection. Liver copper levels were high in two calves (15,100mg/kg and 20,300 mg/kg dry matter; reference interval [RI] 314 to 7,850), and serum vitamin E levels were low (0.9µmol/L and 1.2µmol/L; RI 3 to 18) – suggesting a multifactorial aetiology to the problem.

Since decoquinate was added to feed and feeders were raised off the hard-standing floor, no further cases have occurred.

In a second case, coccidiosis was confirmed in a group of four-month-old to seven-month-old calves, turned out two weeks previously, that were scouring and in poor condition despite in-feed decoquinate.

In excess of 50,000 coccidial oocysts were found in a faeces sample, of which 96% were Eimeria alabamensis. This Eimeria species is typically a cause of coccidiosis in grazing youngstock, particularly shortly after turnout in the spring, and the farm had a history of E alabamensis at pasture.

Parasitic gastroenteritis (PGE) was confirmed in youngstock in several herds – in animals from 2 months to 18 months of age, and with strongyle egg counts as high as 10,700epg.

Ostertagiosis was confirmed in one group of thin, weak, 18-month-old beef animals; 4 of 23 had died. Five animals had pepsinogen levels between 2.9IU/L and 4.6IU/L (levels greater than 2.5IU/L indicates abomasal parasitism likely to be associated with clinical disease).

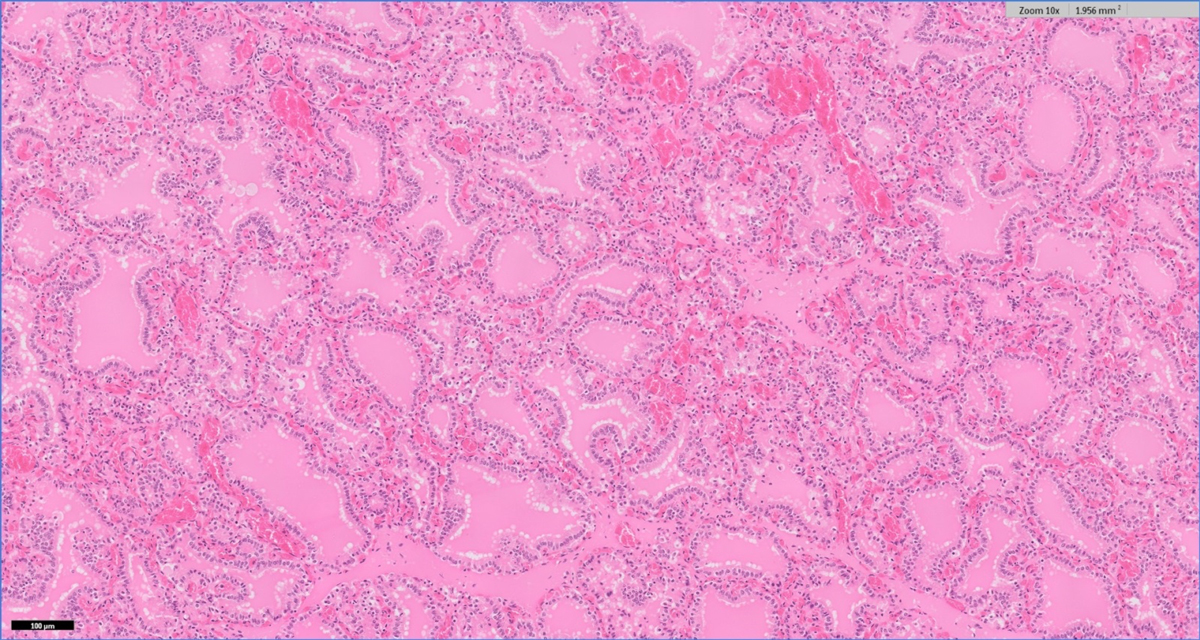

PME of a poor-doing Friesian cow revealed a cobblestone appearance to the abomasal mucosa. Histopathology was consistent with severe chronic hyperplastic abomasitis with mucous metaplasia – changes typical of chronic ostertagiosis. Adult cows suffering from immunosuppression due to other diseases – for example, fasciolosis – or close to calving may suffer from type-two ostertagiosis.

In sheep and goats, PGE was confirmed in several flocks – with strongyle egg counts as high as 33,800epg. Reported signs included weight loss, scour and sudden death.

In animals with higher counts, haemonchosis was often suspected. This was confirmed in a Texel-cross lamb, one of two to have died in a group of 18, with pale mucous membranes seen on PME.

A high strongyle egg count (11,000epg) was found in faeces and numerous adult Haemonchus contortus worms were seen on examination of abomasal contents.

In one flock of dying ewes, high pepsinogen levels were detected (up to 3.7IU/L), consistent with teladorsagiosis; while a strongyle egg count of 6,400epg was found on PME of one animal, with histopathology of abomasum and intestines revealing abomasitis and enterocolitis most likely due to PGE.

Failure of benzimidazole treatment was suspected in a herd of goats (assuming the samples had been taken 14 days to 16 days post-drenching), where five of six pooled faeces samples taken post-treatment had egg counts between 700 strongyle epg and 2,100 strongyle epg.

It was advised that potential reasons for treatment failure were investigated – for example, dose given for weight, technique used, calibration of equipment, product storage and expiry date. If these could be ruled out, benzimidazole resistance was likely.

Fasciolosis was detected in a number of animals in both suckler and dairy herds, and in several sheep flocks by fluke microscopy and coproantigen ELISA.

In one case – after fluke infection had been confirmed in a PME animal from a zero grazed Holstein-Friesian dairy herd – one positive fluke egg count was found in 10 faeces samples, and 5 of the 9 negative samples were positive on fluke antigen ELISA. The latter test is capable of picking up late immature – as well as adult – fluke infestations and is not affected by the intermittent shedding of fluke eggs.

In one sheep flock, treatment failure was suspected with positive coproantigen ELISA results in animals that had been treated with a combination flukicide/anthelmintic four weeks earlier.

Among the many cases of Johne’s disease diagnosed on serology and faecal PCR was a 15-month-old heifer with illthrift and scour that had not improved despite anthelmintic and flukicide treatment. A number of cases also were seen in 18-month-old animals.

In sheep, positive cases on serology included a three-year-old Dorset ewe that had been losing weight for nearly six months, a two-year-old Saanen ex-milking goat with weight loss and intermittent scour, and a 30-month-old goat that had kidded six months previously and was now emaciated.

It was also detected by faecal PCR in a number of flocks.

Several cases of Salmonella-associated scour were seen.

Multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar 4,[5], 12:i:- phage type DT193 – a variant of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium – was isolated from the faeces of a three-year-old Holstein animal that died after a few days of scour and lethargy; and from one of a number of 10-month-old Holstein-Friesian barley fed calves that were recumbent, dehydrated and with a history of bloat.

Two further isolations of S enterica serovar typhimurium – including the variant Copenhagen – were made from faeces of adult dairy cattle.

S enterica serovar Newport was isolated from a three-week-old calf with enteritis at PME, and from a weak, scouring, recently calved Holstein cow.

S enterica serovar Dublin was isolated from:

All were in different herds.

Salmonella oslo was isolated from a three-week-old dairy calf with concurrent cryptosporidiosis and rotavirus infection, and S enterica serovar Montevideo was isolated from a five-year-old Holstein-Friesian cow with mucoid scour.

Other Salmonella cases, where the serovar is still to be confirmed, included:

S enterica subspecies diarizonae serovar 61:-:1, 5, 7 was isolated from a thin Cotswold Longwool ewe with watery scour. This animal also had a slight nasal discharge and had had respiratory issues earlier in the year. The serovar is known to be a cause of chronic proliferative rhinitis in sheep.

Cerebrocortical necrosis (CCN) was considered the most likely cause of blindness in three five-month-old calves, one of which partly responded to vitamin B1 administration.

Histopathology of the brain from one of the calves detected severe bilaterally symmetrical necrotising encephalopathy. The changes were limited to the cerebral cortex, which is most suggestive of thiamine-dependent encephalopathy.

CCN also was diagnosed on brain histopathology on a 15-month-old Lleyn gimmer sheep that presented in lateral recumbency, with opisthotonus and leg paddling.

Hard feed had not been recently introduced, but some cases of CCN have been reported when a change of pasture has occurred – as was the case here.

Among the many cases of likely copper deficiency was an 18-month-old Simmental heifer with marked weight loss, anaemia and watery scour since turnout; plasma copper was 3.1µmol/L (reference interval [RI] 9µmol/L to 19µmol/l).

Low copper levels also were seen in:

A low liver copper level (171µmoL/kg dry matter; RI 314 to 7,850) was detected in a three-month-old vaccinated lamb that was found dead at grass. The PME only identified scour, with a low count of 600 coccidia opg found in a faeces sample.

Low glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) levels consistent with selenium deficiency were reported in several herds and flocks – in both monitoring samples and samples from animals with reported illthrift.

Poor fertility was also reported in one Limousin-cross suckler herd. In one notable example, 4 of a group of 12 6-month-old to 18-month-old Shorthorn cattle suffered rapid weight loss over a week or so; all had low GSH-Px levels (5U/ml to 13U/ml RBC; RI more than 30).

Low liver selenium levels (0.56mg/kg and 0.58mg/kg dry matter; RI 0.9 to 1.75) were reported in a three-week old suckler calf and an eight-month-old dairy calf in two herds where no mineral supplementation was practised.

Several cases of cobalt deficiency (vitamin B12 levels lower than 221pmol/L) were reported in sheep flocks.

Low levels were seen in screening samples and in cases of illthrift, including in a group of four-month-old goat kids with concurrent PGE.

It has been suggested parasitic infection may reduce the synthesis of the intrinsic factor needed for vitamin B12 absorption from the gut.

Concurrent selenium deficiency was seen in several sheep flocks.

Low dietary iodine status was detected on plasma inorganic iodine testing in several herds and flocks – both on routine screening, and in animals with signs including stillbirths, poor condition and infertility.

In a number of cases, concurrent selenium, cobalt or copper deficiency were also reported.

Hyperplastic goitre was confirmed on histopathology in 1 of 9 out of 20 calves stillborn in a dairy herd; the thyroid weighing 38g. Glands weighing more than 30g are likely to be abnormal. Thyroids from two other stillborn calves in the herd – weighing 21g and 22g – were unremarkable on histopathology.

In a second dairy herd experiencing stillbirths and premature calves, histopathology of the thyroid gland from a calf detected a mixture of collapsed follicles containing only small quantities of colloid, and enlarged follicles containing moderate to abundant colloid, with the latter follicles occasionally showing small papillary projections indicative of a previous hyperplastic response.

The variation in follicular size suggested iodine deficiency had been corrected by recent supplementation with iodine or removal of goitrogens.

Manganese deficiency was suspected in a flock where both lambs and ewes had abnormal joints, with levels ranging between 1.3mg/L and 1.9mg/L.

Relatively little information exists on normal manganese levels in sheep, but, in one reference, it was suggested levels below 2mg/ml may be indicative of deprivation in young lambs (Suttle, 2010)*.

Zinc deficiency was confirmed in an inappetant pygmy goat with poor body condition and coat loss when a serum zinc level of 6.9µmol/L (RI 10.7 to 19.9) was detected.

Vitamin E deficiency (0.2µmol/L to 2.2µmol/L; RI 3µmol/L to 18µmol/L) was confirmed in ill-thriven six-month-old Holstein-Friesian calves.

Vitamin A deficiency was diagnosed in preweaned dairy calves with “spectacles” around their eyes and poor growth rates; 9 of 11 samples were low in vitamin A (0.29µmol/L to 1.27µmol/L; RI 0.87 to 1.75). No evidence existed of copper deficiency.

Among the many cases of hypocalcaemia was a dairy herd with a history of retained placentas and milk fever where four out of samples had low calcium levels.

Six of the seven cows also had suboptimal urea levels (lower than 3.6mmol/L) – suggesting a lack of rumen-degradable protein, caused by either inadequate levels in the diet or insufficient intake.

Fatty liver was suspected in a 10-year-old Friesian cow post-calving, with a body condition score of five out of five, poor milk yield, mild pyrexia and mild mastitis; a non-esterified fatty acid level of 2,657µmol/L was found on blood sampling.

Two cases of copper toxicity were confirmed this quarter.

In the first, a recumbent cow three weeks off-calving failed to respond to treatment for milk fever and was found to be severely jaundiced, had haemoglobinuria and the serum appeared haemolysed. Although blood copper was only mildly raised at 25.2µmol/L, liver copper was markedly elevated at 25,200µmol/kg dry matter, consistent with copper toxicity.

The cow had received a bolus containing copper at drying-off, and it was advised this practice was stopped and the copper content of the ration reviewed.

The liver copper level was below that required for the Food Standards Agency to be notified of a potential food safety incident, but it was advised any further cases were screened for liver or kidney copper levels.

In a second case, two nine-month-old rams were dipped and, within two days, had progressed from lethargy to recumbency, pyrexia and death. PME showed evidence of jaundice, livers were enlarged and kidneys were black.

Again, a blood sample taken from one animal before it died had only a mildly raised copper level (21.4µmol/L). However, histopathology revealed acute renal tubular injury suggestive of haemoglobinuric nephrosis; and acute hepatocellular necrosis with biliary stasis and intrahistiocytic copper, consistent with copper poisoning, though assessment of kidney tissue copper levels was recommended to help confirm the diagnosis.

The stress of movement, handling and dipping may have precipitated a haemolytic crisis in this case. Assessment of dietary copper levels was again advised.