29 Oct 2018

Philip Elkins looks at how to investigate transition issues, the risk factors and ways to increase success, in the second of two parts.

Image: Foto-Ruhrgebiet / Adobe Stock

In the first of this two-part article (VT48.37) the author described the stages of transition and how, as advisors to our farms, we can assess transition success.

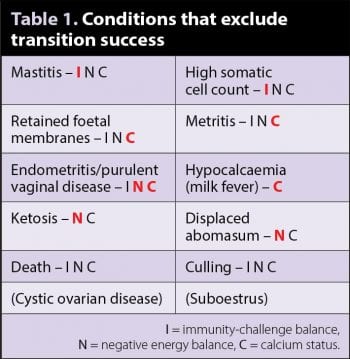

Transition success was defined as: “A cow has successfully transitioned when she has reached 30 days in milk, having had none of the diseases in Table 1, and having reached a suitable expected milk production level.” The diseases in brackets in Table 1 require joined-up record keeping, together with an extended period of analysis, thus, can be included at the practitioner’s discretion.

Part two will cover how to investigate transition issues, including identifying risk factors and potential steps to increase success. Having diagnosed a substandard transition performance, and engaged a farmer in the importance of transition cow management, the next stage is to investigate specifically how the cows are failing to transition and what management factors are contributing to this.

Due to the complex interactions between transition cow diseases, and the multifactorial nature of many of them, a logical approach is needed to best advise an appropriate course of action. This involves looking at three stages in turn: disease conditions, biological outputs and inputs.

The disease list in Table 1 is a good starting point for investigating transition failure, although it is not complete as it will not include subclinical conditions, which, in themselves may not constitute a transition failure, but do contribute to the overall costs of disease and drive the direction of any investigation. Two of these specifically are subclinical mastitis, as defined by a somatic cell count greater than 200,000 cells/ml, and subclinical ketosis, as defined by a β-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) level greater than 1mmol/L, which are both cost-effective to measure and easily accessible.

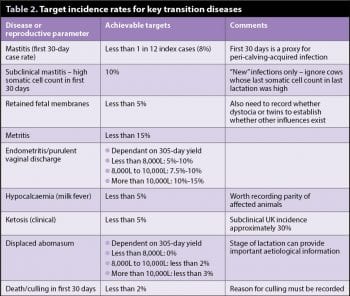

Having said in the previous article setting a target for transition success rate should be bespoke and targeted for each farm, maximum disease rates have been published for many of the specific diseases around transition. This allows prioritisation and focus of the investigation, although it is worth bearing in mind the definition and diagnosis of those diseases – endometritis/purulent vaginal disease rates will be influenced by the method of detection (obvious external discharge, ultrasonography or vaginal examination by either a gloved hand or a device), frequency of detection (frequency of vet visit) and timing of detection (days in milk). These factors must be borne in mind when comparing farm data with published targets (Table 2).

By assessing the rates of individual transition disease, an investigation into the management of preventing transition failure can be appropriately targeted.

In this context, the relevant biological outputs can be described as assessable parameters, which, in themselves, are not diagnostic of diseases, but are associated with both increased levels of disease and specific areas of management/prevention. This is best explained with a specific example: monitoring blood calcium levels after calving does not specifically diagnose a clinical disease (as clinical hypocalcaemia is diagnosed by a clinical picture in association with lowered blood calcium), but increased prevalence of subclinical hypocalcaemia is associated with increased rates of displaced abomasum, ketosis, retained fetal membranes and metritis, as well as a delayed return to normal cyclicity1. Subclinical hypocalcaemia is directly related to management and nutrition of pre and post-calving cows.

These biological outputs can be generally categorised into three distinct, but overlapping, sets – those associated with immunity-challenge balance, negative energy balance or calcium status. In Table 1, the letters following each condition indicate the category the disease is associated with. A large overlap is clearly seen; however, the primary associated category (in red; the author’s opinion) gives some indication as to the most fruitful biological outputs to monitor. It is worth noting here the role inappropriate farmer/vet interventions may play in increasing the rate of postpartum uterine infection.

The biological outputs to monitor in each set are as follows:

In the author’s experience, the outputs in Table 3 give the best snapshot when first investigating transition issues. The targets set for these parameters are the most severe published for two reasons: levels outside these are associated with increased disease, and these levels are consistently achievable on well-managed herds. Conveniently, for each of these parameters, a cut-off of 10% above/below the relevant target would be an appropriate action point – that is at which an intervention could be beneficial and economically viable.

Having identified an area of interest through observing disease rates, and investigating biological outputs, an investigation into the relevant inputs should be started. Inputs could also be called management factors or environmental factors. These factors are, however, far too numerous and extensive to be covered in one article.

Once you have narrowed down the area with the previous investigation it is important to consider a number of questions – and where the answers are negative, consider the inputs that are limiting them:

Through using objective assessment of biological outputs and disease levels to demonstrate an issue, and target the questions and then subjectively assessing the aforementioned questions, failures of management around transition can be identified.

For example, if mastitis rates in the first 30 days are 30%, with 40% of cows scoring two or three in udder cleanliness, and the environment is not conducive to keeping cows clean, a conversation can be had with the farmer around how better to achieve that using published indications for best practice management of these cows – that is, do they have 1.5m2 of bedded area per 1,000 litres over 305 days’ production in the transition area? Is any non-bedded area scraped daily? Is the bedded area cleaned and disinfected every two weeks?

Although these are all evidence-based assessments with a proven association with an increased risk of mastitis, the practicalities of solutions may be different on farm. If the shed in question is poorly draining, the bedding may need to be cleaned out more regularly, with new bedding added more frequently. If the shed is considerably understocked, the opposite may be true. If straw quality is poor, more may need to be added, or an alternative sourced.

At this point, having worked out the likely inputs or management factors that have contributed to transition failure, solutions must be found. It is absolutely integral to this process clients are involved in forming those solutions. They know their farm much better than you, as well as their working patterns. They know what is achievable and what is not. You can guide the conversation and provide information on the likely success or not of changes, but, ultimately, if the farmer does not buy into them they will either not take place, or not be successful.

Facilitating knowledge transfer on farm will also be key to the successful implementation of changes – making sure all the staff involved understand exactly what changes are being implemented and why it will lead to much better engagement.

It is worth remembering, as vets, we have unique access to a number of tools that can assist in transition disease control. One of my key clients always challenges me that these are only ”sticking plasters”. Yet multiple experiences show, even with the best management and commitment to perfection this client shows, every so often “sticking plasters” are needed and, in most cases, farms will not get as close to perfection as this farm does.

These products are primarily biologicals, that is products that have an effect on the cow to minimise disease or the effects of disease, rather than those that treat diseases directly. Specific examples of this worth considering in a targeted approach include controlled-release monensin boluses, calcium boluses, ruminal support drenches and vaccines.

Each of these products has a role to play on certain farms, and when discussing these, we need to use the knowledge and resources available to us to ensure they are being used in a way that maximises the benefit to the farmer and, just as importantly, the stock.

At this point, having agreed with the farmer what steps are actioned, our role is complete, isn’t it?

Absolutely not. Having convinced the farmer of the benefit of monitoring transition success, it would be churlish not to build on this. At the very least, continue to monitor this holistic parameter. Equally importantly, this is an opportunity to put in long-term monitoring plans for disease rates, biological outputs and inputs. For example, a transition yard (unless it changes) has a capacity for cows at an appropriate stocking density for whatever is the limiting factor – water provision, feed space, usable cubicles/lying space or loafing space.

If you know that number, the author would challenge you to visit the transition yard and count the cows after every routine. How often does it pass that magic number for appropriate stocking? As stocking density is a fluid parameter, checking this annually could lead to either overreaction or complacency.

Keeping clients engaged in achieving transition success should lead to happy, healthy cows, happy farmers and, hopefully, happy vets. Who doesn’t love seeing cows thrive?