15 May 2017

David Harwood reveals findings from an unused audit summary on cases of cattle culled in England and Wales from 1999 to 2003.

Abomasal torsion. A simple displaced abomasum is often difficult to confirm at postmortem.

While sorting through some files for a talk I was to give, I came across a summary of an audit I had prepared with my colleague Eamon Watson while we worked for the Veterinary Laboratories Agency (VLA), now the APHA, at the regional laboratory in Winchester.

The summary findings were never published, due to several reasons, and have languished on my memory stick waiting to be rediscovered. It is suggested, apart from tyre wire disease (which has undoubtedly decreased in incidence), the findings of the audit would be very similar if undertaken again today.

Veterinary practitioners working in the farm animal sector during the period covered by the survey may well remember having their casualty slaughter cattle certificates and the decisions made therein scrutinised for accuracy, and the decisions they made at the time of slaughter or shortly after.

Following the identification of bovine spongiform encephalopathy in the UK in 1986, a series of control measures were put in place to protect the consumer. One such measure was the “over 30-months scheme”, which removed older cattle from the food chain, but allowed for compensation to be paid. This compensation also applied to casualty cattle slaughtered on farm that were subjected only to antemortem inspection by the attending vet. As part of an audit process, a number of these casualty animals were selected and allocated on a convenience basis for postmortem examination to a regional laboratory of the VLA.

Data from casualty slaughter cattle can be used as one source of information to help understand and quantify the causes of involuntary culling of adult cattle in Great Britain (Watson and Cook, 2008). This short communication described the findings in a small survey of 484 on-farm casualty slaughtered adult cattle, subjected to laboratory postmortem examination between June 1999 and February 2003. This study was interrupted between March 2001 and May 2002 as a result of the UK foot-and-mouth disease epidemic, but was continuous throughout the remainder of the period – totalling 30 months.

A total of 225,273 cattle were slaughtered as on-farm casualties during the study period (Rural Payment Agency, personal communication), with the 484 carcases examined representing 0.22% of the overall total, with a monthly variation of 0.1% to 0.43%.

A postmortem examination of each carcase was undertaken at 10 regional laboratories by veterinary investigation officers – all experienced in cattle postmortem procedure. To ensure consistency, each examination followed an internal standard operating procedure. The carcase was only subjected to a gross pathological examination. The emphasis during each examination was for the pathologist to assign a “reason for casualty slaughter”. This was based on postmortem examination findings and from written information provided on the accompanying certificate, which was completed by the vet who clinically examined the animal prior to slaughter.

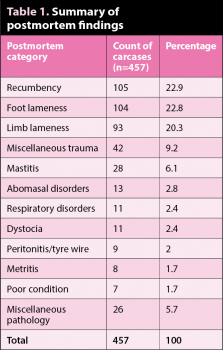

Of the 484 carcases examined, 5 were too autolysed for accurate examination and no gross pathology was evident in a further 22 carcases. The remaining 457 carcases examined – in which conclusive pathology was evident – were subdivided into 12 categories (Table 1).

Four categories – recumbency, foot lameness, limb lameness and miscellaneous trauma – accounted for 344 (75.3%) of the 457 carcases showing pathology. The requirements for casualty slaughter on farm inevitably relate to those conditions that would, under welfare legislation, prevent transportation of the live animal. It is, therefore, not surprising recumbency and foot and limb pathology were the most frequently recorded findings.

Causes of recumbency included pre-calving recumbency (a combination of full/near term pregnancy and poor body condition of dam), cachexia, and recumbency as the primary presentation in cattle with an associated mastitis or metritis.

Septic pedal arthritis/solar ulcer was the predominant finding in those carcases in which foot pathology was evident – accounting for 76/104 (73.1%) of this category. In all these cases, foot lameness was the primary reason for casualty slaughter and these figures were not, therefore, directly comparable to references describing UK clinical foot lameness studies in which solar ulceration rates of between 12% (Russell et al, 1982) and 28% (Murray et al, 1996) were recorded.

Of the 93 carcases in which limb (as opposed to foot) lameness was present, 22 (23.7%) had a dislocated or fractured hip joint. Septic arthritis (defined as being swollen with purulent exudate within the joint capsule) was seen in 22 cases and distributed between the hock (n=6), carpus (n=4), stifle (n=3) and fetlock (n=2), with the remaining cases involving two or more joints. A further 22 cases had chronic arthritic disease, most commonly, the hip (n=11) and stifle (n=5) joints. Other cases of limb lameness were soft tissue damage around the hip (n=9) or other site (n=12) and fractured long bone (n=6).

Table 2 shows the other sites of traumatic injury recorded. Ribcage lesions were considered to be the primary lesion in six carcases examined and a further six cases were considered to have rib fractures secondary to primary foot or limb pathology. Blowey (2007) postulated such an association may be the result of cubicle injury as lame cows lie down in a cumbersome manner.

Of the 28 diagnoses of mastitis, 18 were recorded as chronic and 10 as acute or gangrenous. Abomasal disorders were recorded in 13 carcases.

Due to the difficulty in confirming an uncomplicated abomasal displacement at postmortem (as carcases are lifted, loaded, unloaded and then hung upside down for postmortem with the potential for repositioning to occur), it was not always possible to confirm the clinical diagnosis at postmortem. Categorisation was, therefore, based partly on pathology (if the abomasum was clearly displaced); in other cases, however, the diagnosis was influenced by the attending clinician’s written description and the absence of any other gross pathological change.

Dystocia was confirmed in 11 carcases, 2 were breech presentations (in 1, the calf was lying free in the abdominal cavity following uterine rupture) and the remainder were normal anterior presentation, but with marked relative fetal oversize or autolysis.

Peritonitis was evident in nine carcases examined. In five of these, a fragment of tyre wire was found in the cranio-ventral abdominal area near the reticulum. This was a relatively common diagnosis during the study period – particularly in UK dairy cattle (Orpin and Harwood, 2008).

Of the seven carcases in which no primary pathology, other than poor condition or cachexia, was identified, chronic fasciolosis was evident in two and gut pathology – suggesting Johne’s disease – was described in a single carcase. No other lesions were identified in the remaining four cases. Diagnoses recorded in the category described as “miscellaneous pathology” included cervical prolapse, vaginal prolapse, third eyelid squamous cell carcinoma, intussusception, pyelonephritis, vegetative endocarditis, fatty liver, liver abscessation and wound breakdown following a caesarean section.

Although historical, the observations from this series of postmortem examinations undertaken between 1999 and 2003 provide a snapshot of reasons for on-farm casualty slaughter of adult cattle that remains relevant today.

Thanks to Eamon Watson, who undertook the statistical analysis of raw data provided, and all veterinary colleagues throughout the VLA who undertook the postmortem examinations.