5 Jun 2017

Jennifer Marsh discusses sheep digestion, methods of improving field pastures for optimum nutrition, and grazing strategies.

Image: Fotolia/Dimas830.

The New Zealand-style system of grazing dairy cattle has increased in popularity in the dairy industry – especially in areas of the country where soil type and climate allow.

While year-round grazing is tricky in most parts of the UK, dairy farms that employ successful grazing systems utilise grass well during the summer months due to strict management routines – ensuring cows eat as much grass as possible, with quality grass growing back following each grazing period.

Grass is a natural source of nutrients for all ruminants and, therefore, has the potential to be a very good feed for sheep too, as it is cheap to produce and easy to manage. Added to this, marketing and health drives within the meat industry have claimed grass-reared lamb to have higher levels of certain nutrients, particularly omega-3 fatty acids, which may have health benefits to humans.

This article aims to cover the basic rules of how to improve pasture management to ensure sheep farmers get the most from grazing.

Before grass management is discussed, it is important to understand the fundamentals of nutrition in sheep, as this is essential if any nutritional advice is to be given. A ruminant has four stomachs: the rumen, reticulum, omasum and abomasum. The rumen in a sheep contains a “soup” of digestive products and microbes, which are fuelled by the food ingested by the sheep. The rumen acts as a large fermentation vat, so, when feeding a sheep, we are actually feeding the rumen microbes, which, in turn, provide nutrients to the animal.

When the microbes are fed correctly they produce the four basic nutrients required for life: energy, protein, vitamins and minerals – and these are available for the host sheep to use. Sheep also require water, which cannot be produced in the rumen and is essential for all life processes, thus fresh, clean water must be provided daily.

Ruminants are often observed chewing the cud and this is an important part of the rumination process. The cud is a mixture of half-digested material regurgitated from the rumen when the sheep is lying down. The cud is chewed and re-swallowed. The act of chewing produces saliva, which contains bicarbonate – a buffering substance that ensures the acidity of the rumen is kept at the optimum level. When the food is swallowed for the second time, it goes straight through the rumen into the next three stomachs and a mix of semi-digested food, microbes and rumen fluid flows through the reticulum, omasum and abomasum.

The abomasum is known as the “true stomach” and, from here onwards, digestion takes place in a similar way to monogastric species, such as humans. Acids and digestive enzymes break down the food and the nutrients are absorbed across the stomach and intestinal walls into the bloodstream, where they can be used by various organs.

Grass provides energy in the form of sugar and fibre, and contains very little starch. Sugar and fibre are broken down by the microbes in the rumen to produce energy. Sugar is digested very quickly and gives an instant boost in energy. Fibre takes longer to digest and is turned into volatile fatty acids (VFAs; propionate, acetate and butyrate), which are absorbed across the rumen wall into the bloodstream. VFAs travel in the blood to the liver and are transformed into available energy forms, such as glucose, which can be used by the sheep for energy.

Energy is measured in megajoules and every animal requires a certain amount of energy for maintenance – that is to stay alive. Other processes require more energy on top of maintenance – for example, a pregnant ewe with twins, or a lactating ewe, will require more energy than a ewe not pregnant or milking. Similarly, a growing lamb will require extra energy to ensure it puts on weight.

Two types of proteins are found in feeds that can be fed to sheep. Rumen-degradable protein (RDP) is broken down by the rumen microbes into its building blocks – amino acids – and then rebuilt into microbial protein. It is this microbial protein that is used further down the digestive tract and provides most of the protein supply required by the sheep.

Digestible undegraded protein (DUP) is not broken down by the microbes and is also known as bypass protein. This protein passes into the abomasum and is broken down by enzymes in the same way as monogastric species. DUP is needed when ewes require high levels of protein – for example, during late pregnancy and lactation.

Grass contains only RDP and, most of the time, can provide everything a sheep needs. Well-managed grass pasture can provide everything a ewe requires, even in late pregnancy. However, if not well-managed, or if weather conditions are poor, a late pregnancy and lactating ewe may need topping up with DUP from other sources, such as compound feeds.

Feed stuffs for ruminants are usually referenced in dry matter (DM) terms. Nutritionists tend to use DM, but farmers often use and understand feeding in fresh weight terms. Using DM makes it easier to compare the nutrient values of different feeds.

With grass in particular, amounts of grass tend to be expressed as kilogrammes of DM per hectare (kg DM/ha). DM is the resulting value once all the water has been extracted from the feed and is usually measured using a drying machine. For example, a fresh weight of 100g, which, when dried, weighs 30g, has a DM of 30%; that is to say, 70g of water evaporated from the sample.

The DM of grass will vary according to the amount of rain. In dry conditions, grass can be as high as 22% DM, but, if it has rained continuously, DM can be as low as 12%. This is a big range, thus it is essential to have some idea of DM if amounts of grass in a pasture are to be calculated. To find out the DM, grass samples can be sent to a laboratory for analysis. Alternatively, farms that graze all the time can buy a DM tester to regularly test instantly and help manage the grazing better.

Understanding how grass grows helps to realise the importance of grazing strategies. Each individual grass plant is called a tiller and perennial ryegrass – the most common grass type found on UK pasture – has three leaves on each tiller. When a fourth leaf begins to grow, the first leaf, which is the oldest, will die off.

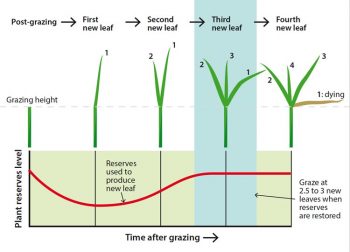

Grass growth usually peaks in the spring and, during peak growth, a new leaf can be produced as quickly as every four to five days. Figure 1 shows the leaf life cycle of a grass plant and how it recovers following grazing.

Many different things affect the amount of grass plants that grow – not least the species and variety. Generally, soil temperatures below 5°C will inhibit grass growth. If temperatures in the soil go above 5°C for five consecutive days, the plant will begin to grow because it will start to absorb moisture and nutrients from the soil. Soil temperature can be measured using a thermometer. This should be inserted to a soil depth of at least 15cm to help a farmer decide when to apply fertiliser. There is no point applying fertiliser if the temperature is below 5°C, as the grass plants will not be growing. Air temperature is also important and is affected by the pasture’s aspect, the farm’s altitude and time of year.

Every plant requires light to drive photosynthesis – generating energy for growth. Longer periods of light provide plenty of energy, whereas short periods result in a plant using up its energy stores to maintain growth. This is why plants start to grow in the spring – as day length increases, growth is stimulated. Plants that grow fast and have large leaves will absorb more light.

To grow fast, grass requires certain nutrients from the soil – the main three being nitrogen, phosphate and potassium. By applying nitrogen to pasture the speed of grass growth can be increased. The optimum height of grass for nitrogen application is 4cm to 8cm (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board [AHDB] Beef and Lamb, 2016). Nitrogen also allows the plant to make use of the other nutrients in the soil.

Water is essential for all living creatures and, for grass, the right balance is important. Too little water results in wilting, which affects how much light the leaves can afford; too much water will affect root growth negatively, and also result in wilting.

To get the best from grazing, grass growth should be measured regularly. The most common method is to use a plate meter or sward stick, but this is not essential as sward heights can, for example, also be measured using marks on a rubber boot, a ruler, or even a beer can. The point is measuring allows a comparison between fields and between time periods, to see how much, or how little, grass has grown and to help decide which field should be grazed next.

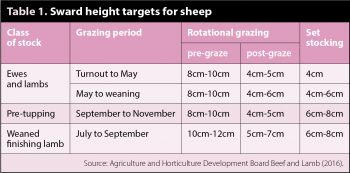

The best method for measuring sward height is to walk a field in a random pattern, usually a “W” shape, taking 30 to 40 readings. To take a reading, place the measuring implement gently on the ground and read the height where the top of the grass leaves come to – ignoring flowers and weeds. It is important areas such as gateways or tracks are avoided as these are unrepresentative of the rest of the field. An average of the 40 readings should be taken and recorded for assessment. Table 1 provides some idea of ideal sward heights for different sheep.

Monitoring the height of grass in a field will help improve utilisation and allow a farmer to make the most of the grass grown. In a growing field of grass, some leaves will always be growing and some dying (Figure 1). A balance should be maintained, as too many dead leaves will stop light reaching the new leaves – also causing them to die. Added to this, a build-up of dead material at the base of the sward uses up nutrients during the decaying process and creates an environment for pests and diseases.

Aim to reduce waste by preventing grass plants reaching the fourth leaf stage by grazing at the correct grass heights. When fields are grazed at the right time, with the right amount of stock, grass utilisation can be as high as 80%, and the amount of dead material is minimised.

However, utilisation is affected by many other factors, including grass quality, type of grass, amount of weeds (especially thistles), nettles and the history of previous grass management. Added to this, as fields are used repeatedly over a season, faeces and urine will affect patches, which will make grass unattractive and unpalatable for animals to eat. This waste must be taken into account when performing grass calculations.

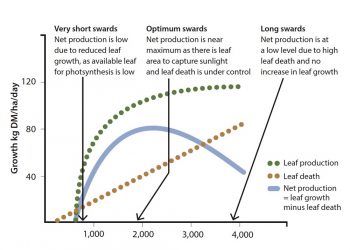

Figure 2 shows how grass production changes at different growth rates. Optimum production tends to be reached at 1,500kg DM/ha to 2,000kg DM/ha. The cover of grass in a field is assessed by the height of the grass, field size and average DM to give the kilogrammes of DM/ha figure. A plate meter will calculate the cover automatically; for example, a field of 4cm to 5cm sward height will give around 1,500kg DM/ha, but a sward where the leaves are starting to bend over will equal around 3,000kg DM/ha.

Arguably, the most common method of grazing sheep in the UK is set stocking, which allows animals to have access to large areas of pasture throughout the season. This can be improved by measuring grass heights and shutting sheep out of fields if the grass is getting too long, allowing these fields to be cut for silage or hay, rather than allowing animals to trample and waste grass that is too long to graze.

Rotational grazing allows the sheep to be moved around a small number of fields based on the height of the grass and can result in higher productivity than set stocking (AHDB Beef and Lamb, 2016). Rotational grazing also gives the pasture a break to allow the grass the chance to regrow. However, water provision must be taken into consideration and more fencing may be required.

Paddock grazing moves the sheep frequently between small paddocks and gives the best grass production per hectare. Stocking densities must always be taken into consideration. Stocking is usually referred to in terms of livestock units (LU) per acre. According to AHDB Beef and Lamb (2016), a high stocking rate is 0.8LU/acre to 1LU/acre (2LU/ha to 2.5LU/ha), and low stocking rates are 0.4LU/acre to 0.6LU/acre (1LU/ha to 1.5LU/ha). A lowland ewe is the equivalent of 0.11LU, whereas store lambs less than a year old are equivalent to 0.04LU (Defra, 2010).

Many ways exist to graze livestock and achieve the best forage utilisation on farm. No one size fits all and it will depend on the farm, field sizes, type of ground and amount of time the farmer is willing to spend on organising the pasture. One thing is for sure, paying more attention to grass growth on the farm can improve the returns from grass and, in turn, have the potential to reduce feed costs.