30 Oct 2017

John Carr and Mark Howells describe approaches to examining populations of these animals on farms to detect signs of respiratory disease.

The skill set required to examine a respiratory problem in pigs not only relies on the veterinarian understanding pathology and microbiology, he or she must also teach the farm staff observation skills to identify early recognition of distress in the animals. Investigation of the respiratory problem must involve the current situation through careful examination of individual pigs, but also events over time, through slaughterhouse and data examinations.

Success in preventive programmes must optimise the batch flow, the environment of the pigs and ensure any medicines and vaccines prescribed are stored and used correctly.

A practising pig vet may spend 70% of clinical time investigating respiratory diseases in growing and finishing pigs.

This short review does not attempt to cover the various pathogens that can affect the pig’s respiratory tract, but explores a method of examination the clinician may find helpful to unravel the underlying causes of respiratory disease on farm. Biosecurity routines, which should be employed to protect a farm from novel pathogens entering pig units, are not considered.

All practising vets know pigs are not the easiest of patients – either as individuals or as a group. Clinicians must always obtain a thorough history to include the state of affairs at the time and the sequence of events that has led up to it. Remember, a population of pigs is made of individuals, so all the diagnostic skills relating to individual animals, and a firm grasp of population medicine workup practices, will be employed in any investigation.

Observe the pigs from a distance to gain an insight into their behaviour before you disturb them, then look for individuals that are acting differently or demonstrating abnormal patterns of behaviour or clinical signs. Do not charge into a room banging on the walls to get the pigs up. This is, unfortunately, practised by many farm managers.

What are the pigs telling you? Look/listen for:

High ambient temperature favours digging and wallowing; pigs make themselves very dirty. This is normal behaviour, but remember pigs are naturally very clean creatures.

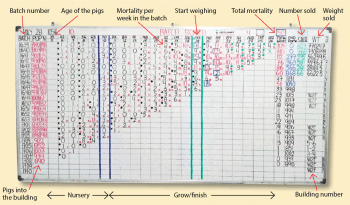

Finishing production boards can be useful to illustrate the development of a clinical problem and should be placed in the staff room so the whole farm team is able to review any issues. These data, fixed by batch, provide a “live” timeline of problems affecting mortality.

The example of a board above shows a swine influenza outbreak in the late finishing period, which was confirmed by serological changes. Graphs can be constructed to demonstrate the mortality within each batch over time and pinpointing periods of risk for the pigs.

It is important to maintain the batch integrity from weaning. This facilitates an assessment of the parity makeup of the batch; more than 25% of gilts in a breeding group is likely to lead to more problems in the finishing herd.

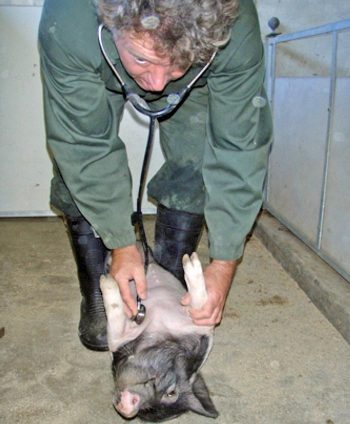

The clinical examination will probably necessitate a combination of samples, and obtaining appropriate samples from live pigs and fresh postmortems.

Serial sampling can be extremely helpful to indicate when a particular pathogen is challenging a population of pigs. This can help to inform decisions about the timing of targeted medication vaccinations – for example, in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae outbreaks.

Collecting saliva provides a simple tool to explore disease patterns on farms. As most of the respiratory pathogens in pigs inhabit the oronasal cavity, saliva can be used to demonstrate the organisms (PCR testing) or provide evidence of exposure (serology). Note oral fluids are a population tool – the sensitivity on an individual is lower.

Of course, finding a pathogen or evidence of exposure on an endemically infected unit may have little clinical relevance. Prior vaccination can also complicate matters, particularly the use of live porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome vaccines.

The postmortem examination must be thorough. Do not just open up the chest and look at the lungs. Systematic inspection of the whole respiratory tract must include all the airways, not just the air exchange system. The defence mechanism of the respiratory tract is diffuse, and includes the stomach and immune system.

A properly functioning stomach, with an intact mucosa to contain its acidic environment, is essential to neutralise pathogens trapped in the mucociliary mucus. Gastric ulceration leads to chronic blood loss, thereby compromising the gaseous transport system around the body, and may lead to a “cardiac” cough and heart dysfunction.

Look for the full range of likely pathological findings:

The logistics of pig production facilitate the examination of a large number of “healthy” animals from a particular farm in the slaughterhouse. Inspecting carcases regularly using standardised recording and scoring systems to grade the changes observed provides an excellent monitoring tool – but ensure you are looking at your client’s pigs.

Samples include nasal swabs, saliva examination (using rope), blood sampling and tissue samples (fixed and cultured if fresh).

The clinician needs to be able to interpret the results. Many of the known respiratory pathogens are normal inhabitants of the nasopharynx. Understand their potential to invade and elaborate virulence factor. The significance of isolates must be considered carefully. Today, the pig clinician is expected to interpret the DNA/RNA sequence to follow epidemiological spread of a pathogen within a region and between farms. This information may inform selection of the most appropriate vaccine. The genetic sequence analysis can be very useful from a biosecurity/epidemiological examination.

Organisms that can be expected to be isolated from a normal healthy pig’s respiratory tract include:

Ascaris suum

On known “positive” farms:

Note large animal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus may also be isolated commonly from central European countries.

The key to the preventive medicine programme for respiratory control is vaccination. The efficiency of a vaccine is partly determined by careful management of the cold storage chain. The vet must make it a priority to ensure medicine storage is adequate at every stage.

During the farm visit, always examine all medicine stores. An infrared thermal gun is an extremely useful tool. A maximum/minimum thermometer should be available to check all fridges and its output should be reviewed during the visit. A temperature logger should be placed in every fridge and the data reviewed once a month. When the temperature is outside the storage zones, these events need to be explained – for example, door opening.

The position of the vaccines in the fridge can also be significant. They must not be in contact with the freezing plate. It can be frustrating when different vaccines stipulate different temperature storage requirements; most need to be stored between 2°C to 8°C, but a few require 2°C to 7°C.

Managing the environment is key to controlling respiratory disease in pigs.

It is useful to consider the environment in four sections: water, feed, floor and air. The clinician has to assess the impact each of these factors may have on the natural defence of the respiratory tract. The mucociliary escalator forms a major part of the intrinsic barrier of the respiratory system against infection, but its function can be compromised in a number of ways.

A poor water supply can decrease the viscosity, which, in turn, will reduce the speed of the escalator, and its stickiness and adhesive properties.

If the feed is very dusty, it may be used as a vector by respiratory pathogens. Destruction of the nasal turbinates in pigs affected by atrophic rhinitis greatly reduces the pig’s ability to filter and remove dust particles from the respired air when eating. Poor feeder management resulting in any periods of feed outage is stressful for pigs and favours the development of gastric ulcers.

While it seems difficult to appreciate how a floor can impact on respiratory health, rough floors cause damage to the coronary band. Colonisation of lesions by bacteria may lead to septicaemia, seeding pathogens into the pleura and initiating pleuritis.

The stocking density of pigs in the building has a major impact on the spread of respiratory pathogens. It is very important to avoid over-stocking and under-stocking. This is a feature of pig flow and understanding this is key to the integrity of “all-in/all-out” batch systems. This approach is the only logical way to create hygienic breaks between batches of pigs.

Most clinicians appreciate the air and ventilation system can have a major impact. But what aspects of air should the clinician monitor?

Are the pigs kept in their thermoneutral zone? This is the temperature zone where the pig does not have to eat specifically to keep its body core stable or it does not have to reduce its feed intake to reduce metabolic activity to cool the body core.

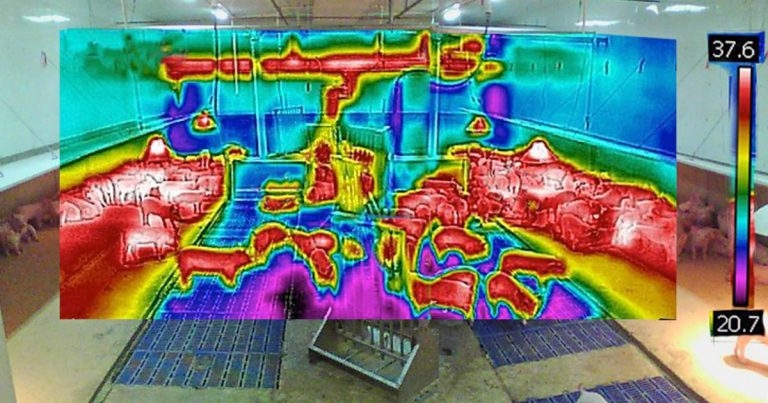

It is important to understand and monitor the thermal balance of the room. An infrared camera can be extremely useful in producing an image that can be explored in detail.

Understanding the thermal balance of the room allows feeding, drinking and lying areas to be set up in a way that encourages the pig’s behaviour to fit the zones, which we create in a controlled environment.

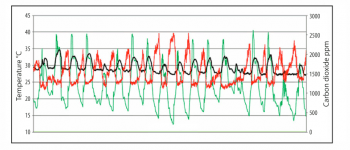

Remote logging equipment enables the farm health team to monitor temperature, humidity and carbon dioxide in real time. Graphical presentation forms part of the overview as to how the building is performing in relation to finishing board data and other clinical signs.

An enormous amount of information is available to the observer, who takes time to look and use his or her senses. These include:

fan speed – inlets, outlets and air movement through the house

To control respiratory diseases, it is vital to get stocking density correct, and practise all-in/all-out so the buildings can be cleaned and repaired before the next group of pigs arrive. This is the cornerstone of all disease control.

The farm team needs to develop a pig flow model based around the farrowing house and the batch farrowing place. Respiratory pathogen control is easier the longer the gap between one weaned batch and the next.

Three-week batch farrowing has several advantages for family farms:

The break in production offered by three-week batching allows for farms to take fewer risks with the possible introduction of pathogens. With three-week batching, semen for AI is introduced into the farm 13 times a year – rather than 52 times under a weekly batching system.

The movement of pigs from the farrowing area to the nursery and finishing houses is also reduced to 13 times a year – reducing the transport risk. This break in production should be extended to all movements including personnel.

The greatest risk to the health of a finishing pig is another pig – particularly a sick or compromised pig on the same farm. Managing compromised pigs forms a very significant part of respiratory health management on any pig farm. Hospital pens should not be placed inside the same building as healthy pigs. Specialised pens should be made available and looked after by staff who do not move from the hospital pens to the healthy pig building.

Another advantage of three-week batching is the small, compromised pigs at weaning are also batched, making the number of pigs in the group big enough to make investing significant time and effort rewarding. For example, a 20-sows-a-week weekly system will have about 24 small pigs a week – just enough for a pen. But a 60-sows-every-three-weeks system will have 72 small pigs – enough to possibly fill a house and keep it separate from the main batch.

This diversion of pigs that are most likely to become sick can help make significant steps towards the basis of an antimicrobial-free farm.

The control of respiratory diseases may also hinge on the control of other pathogens and stressors on the growing pig – for example, mange (Sarcoptes scabiei var suis) can cause sufficient distress in a group of pigs that a subsequent “outbreak” of clinical respiratory disease is seen on the farm.

To investigate an outbreak of respiratory disease on a commercial pig farm, the modern pig population clinician needs a range of skills. Individual pigs, the population as a whole and its sub-groups must be considered in turn. Assessment of environmental factors and an understanding of the intricacies of population dynamics are essential if we are to influence and resolve acute and long-term respiratory disease. We have to be able to design a comprehensive programme that can be understood and implemented by the farm health team.

Vets practising population medicine require a multidisciplinary approach, which must encompass investigating the farm itself, the people working on it and the pigs at every level. Without doubt, if we are ready to meet this challenge, our pigs are worth it.