1 Nov 2022

Phil Elkins explains why dairy vets should learn about this and the benefits it offers for their client relationships.

Image © Suslov Denis / Adobe Stock

In simple terms, our role as dairy vets is to advise on health and welfare, so why should we be interested in milk pricing schedules?

Our clients are commercial enterprises and, as such, our advice needs to consider both the cost implications, as well as the return on investment. But then we can base that off headline milk price, surely?

Again, it is not that simple, as will be demonstrated in this article, and the importance of knowing and understanding the milk price schedule of your clients will be demonstrated.

The milk price schedule covers all aspects of the payments from processors to dairy clients for their milk. This obviously involves the headline price per unit, but also deductions and premiums for a number of other factors.

A large variation exists in how milk price schedules appear and what is included in them. These differences can be responsible for large cost implications. If we consider bactoscan, for example, two milk processors have no deduction or premium for a value of 30,000. However, one has graduated deductions or premiums from this point – so, the lower the better. The other penalises 0.1 pence per litre (ppl) from 30,000 to 50,000, and 0.5ppl from 50,000 to 100,000, but no further premium for below 30,000.

If we consider a bactoscan of 51,000, the difference between the processors is 0.21ppl versus 0.5ppl, which over a typical 1.5 million litre farm equates to nearly £4,500, but farmers in both situations are ultimately losing money based on milk hygiene.

Most processors do not publicise their milk price schedules, as they are commercially sensitive, and, as such, the best way to get milk price schedules is to ask your clients. The commercial sensitivities of these documents should be respected and the details should not be shared with other clients, and only used to improve the advice you give to your clients.

The images included in this article are from milk pricing schedules with all company information removed and are used to demonstrate principles rather than for specific calculations. All have been received in the past 12 months.

The headline milk price is usually quoted on a per litre or per kilogram basis based on a standard litre. While these may vary slightly between processors, the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB) defines a standard litre as follows:

When looking at milk price tables assimilated by industry bodies, it is these figures that are considered when calculating the standard litre price. However, these may differ drastically from the price paid to your clients.

As you can see, milk constituents – namely protein and fat percentage – form part of the formulation of price paid for milk. Historically, almost all milk price schedules consisted of a base price, and then penalties or bonuses based on fat/protein level. This is still the case with liquid milk processors. This traditional payment rate would usually take the following format:

As you will see, it becomes easy to identify the influence of increasing constituents on a per-litre basis, but harder to surmise the overall income should this come with an associated reduction in milk volume.

These typical contracts usually come with a floor and a ceiling – a level below which the penalties for constituents become considerably higher, and a value beyond which surplus fat and protein comes with scant reward.

However, for many manufacturers (cheese or cream, for example), contracts are now based on production of fat and protein, with differential payment rates based on the end product, with no direct payment per litre of milk. If you consider Figures 1a and 1b, this shows the headline payment for two different manufacturing processors.

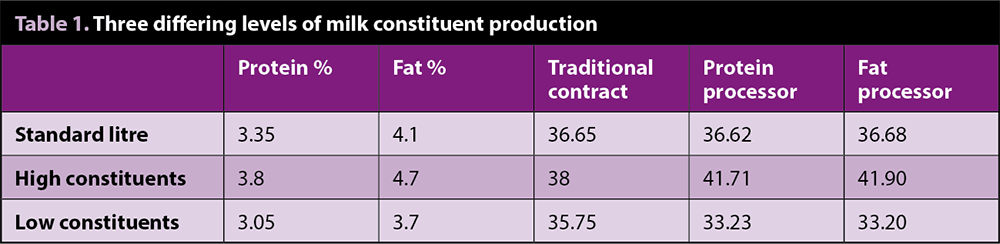

An example clearly demonstrates the difference in motivating factors between differing contracts: we can set a traditional contract at 36.65ppl with 0.1ppl for every 0.1% protein deviation and 0.15ppl for every 0.1% fat deviation from the standard litre (which would not be atypical). Comparing this with the two processing contracts for three differing levels of milk constituent production (Table 1), an obvious disparity is present in how much the change in constituents affects the milk price received, with the traditional contract seeing less penalty/reward for altered constituents.

What does this mean for us as vets? In the case of the traditional contract, the focus should be on optimised milk volume production, even if that is to the detriment of milk constituents, as long as little to no impact is had on animal health. Whereas for the constituent contracts, the focus should be on cost-effective production of milk protein and fat, respectively – even if this is associated with a milk volume reduction.

Milk production levels can commonly influence milk price in one of two ways – volume bonuses and seasonal production levels.

Volume bonuses represent both the efficiency of collection for the milk processor and the value to the processor of the farmer. These are generally sequential – a bonus for every 1,000 litres per collection on average – with a maximum on the bonus. This maximum relates to collection capacity and is usually either 16,000 or 24,000 litres per collection (equating to around 3 million or 4.5 million litres of production per year).

The bonuses can be considerable, equating to up to £75,000 per year.

While each additional litre may not equate to a large rise, consistent increase in production can lead to large financial rewards as the volume bonus is paid over every litre produced.

Adverse somatic cell count and bactoscan readings offer vets an opportunity for involvement that is both cost effective for the farmer and rewarding for the vet.

Two pieces of information from the milk price schedule exist that should be known with regards to milk hygiene – the threshold for the premium band – anything below this should be seen as a penalty – and the cost implications of crossing this threshold. This information is contained in tables such as shown in Figure 2.

Milk processors can use a number of different mechanisms to reward production when the need is highest or to disincentivise production at times of oversupply. The simplest of these is seasonality: processors will predetermine a premium or a penalty over every litre produced at certain times of the year.

A and B pricing is a slightly more complex method of achieving this – A litres will be paid at the standard price and for a monthly volume equivalent to average production. B litres are those above and beyond the average production, and demand either a highly inflated or deflated price. Forecasting also allows processors to plan accordingly, with a premium paid if milk volumes are within a small margin of those predicted.

While as vets we may have little influence over these factors, we need to consider their implications on herd management. For example, a block calving herd may benefit health-wise from a shift of block to a time of greater forage availability. However, this may need to be balanced against the differing milk price for production at peak levels.

Equally, some cows may be designated as culls carried on farm at a negative margin against inputs to achieve forecasting levels and, therefore, increase milk price across the entire herd.

An increasing number of processors are now introducing premium schemes to reward clients that match their aims. These usually have multiple qualifiers, including being in the top band for somatic cell count and bactoscan, having acceptable milk constituents, and achieving various other key performance indicators. These premium schemes may be handsomely rewarded and, as such, the pressure to maintain the qualifying criteria is high.

This introduction to the milk price schedule is best supplemented by asking your clients if you can see theirs, comparing it with their current performance, and looking for opportunities to optimise returns.

Even undertaking the first two steps will allow you to better understand and align with the client’s business needs. The main advantage of this is ensuring wider advice – in particular with regards to nutrition and hygiene – is supported with appropriate financial awareness.

However, a number of other utilisations of this data exist, of which the author will share two examples:

Unfortunately, these two examples are often not simple to calculate and may require some basic spreadsheet skills, but the benefits for the farmer, as well as your relationship with them, can be rewarding.

Many unseen ways exist in which familiarity with the concept and specifics of milk price schedules can increase the veterinary value to farmers. The first step is to engage.