12 Nov 2018

Paul Burr breaks down ways to counter these infections via various control and prevention methods.

Image: gozzoli / Adobe Stock

Bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD), infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR) and Salmonella are three important endemic diseases in UK cattle. For BVD, national control programmes are underway throughout the British Isles, but a presentation at BCVA Congress noted evidence of active BVD in more than a third of submissions for investigation of respiratory disease.

Catastrophic IBR breakdowns in naive herds are relatively rare and IBR is less frequently found in respiratory outbreaks in calves than other respiratory viruses, but published evidence suggests chronic subclinical infection in a herd can have a substantial effect on performance. The extent and full effects of Salmonella infection in the national herd is perhaps least well understood and may be underdiagnosed.

Acute salmonellosis in cattle can cause serious economic losses in affected herds, as well as infection of humans through occupational exposure (contact with faeces of infected animals) and consumption of contaminated meat or dairy products. National control programmes are underway for Salmonella elsewhere in Europe – the UK is no doubt some way from this, but it would be very useful to have a much better understanding of prevalence in the dairy and beef sectors.

A significant challenge prior to tackling any infectious disease on farm is demonstrating to the farmer a problem exists.

Antibody testing of both milk and blood samples has been used in BVD, IBR and Salmonella monitoring programmes worldwide, and is a straightforward way of assessing whether disease is present in the herd (Table 1).

Bulk milk is an easily collected sample and can be a useful starting point for discussion in a number of infectious diseases. For BVD, a low or negative bulk tank antibody titre is a very strong indication the herd is free of active BVD. A strongly positive titre indicates active BVD or perhaps vaccination (with a modified live vaccine) in the past few years. Bulk milk PCR tests for virus are also used to indicate whether a BVD persistently infected (PI) is contributing to the bulk tank on the day the sample is collected.

For IBR, a negative result on the standard test indicates the milking herd is free of IBR, and as the bulk tank titre rises the estimated proportion of positive animals in the herd also rises. Due to the lower sensitivity of IBR glycoprotein E ELISAs, a negative result on this test cannot prove a herd is completely free of wild-type IBR infection; a negative result implies less than 10% to 20% of the herd is positive for IBR.

Bulk milk antibody testing for Salmonella is also usefully part of initial screening or if clinical disease suspected. With recommended test cut-off points the test has high specificity, but sensitivity is not certain as we do not know what proportion of animals must be antibody positive to achieve a test-positive result. As such a positive result strongly suggests a significant Salmonella problem, a negative bulk tank result implies a lower prevalence or perhaps a negative herd.

Most vets and many farmers will be familiar with using a BVD antibody check test of five unvaccinated animals from each management group in the age range of 9 to 18 months. This sample group can be used in beef and dairy herds, and also has application for assessing the IBR and Salmonella status of a herd. Due to the rapid spread of BVD infection in a group if a BVD PI is present, for BVD a check test can give a very strong indication of overall herd status and is accepted as such by Cattle Health Certification Standards and national eradication schemes.

While for IBR and Salmonella a negative youngstock check test would not prove no infection in the herd, it would suggest lower levels of infection. If repeated on a number of occasions over a period of years, and supported by bulk milk test results, confidence in herd-negative status would increase. A positive IBR or Salmonella result in a check test is a strong indication of infection in the lifetime of that animal due to the high specificity of the tests used.

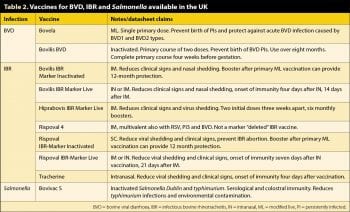

BVD control is critical to the success of a herd. If evidence suggests no BVD is present, the farm should concentrate on keeping it out. Where any concern exists over the ability to maintain strict farm boundaries, and quarantine and test every added animal, BVD vaccination of breeding females should be considered as insurance against a catastrophic BVD breakdown.

Where active BVD is suspected, a programme to control and eradicate BVD will have a dramatic positive effect on herd health and welfare. BVD eradication can be achieved if every animal is tested for BVD virus, any PIs are identified and removed, and all calves tested for BVD virus for a calendar year after the removal of the last known BVD PI.

Again, BVD vaccination can be very useful to reduce the risks of further BVD PIs being born, and it is essential further PIs are not purchased and brought on farm.

IBR eradication can be challenging, as the presence or addition of a single latently infected animal to the herd can result in a full herd breakdown if the virus recrudesces when the animal is stressed. Herds with little or no immunity to IBR must take great care to quarantine and test added animals, and, unless it is certain no IBR carriers are present, they are at risk, even if the biosecurity is perfect.

IBR vaccination is worth considering in most herds and vaccine can be used during a herd IBR breakdown to reduce transmission of virus. Vaccination can protect calves and heifers from infection, and, over a period of years, eradicate IBR from the herd as wild type infected animals leave and are replaced by marker vaccinated, wild-type, IBR-negative animals.

Spread of Salmonella between cattle herds is most commonly through movement of infected, but clinically healthy, carrier animals or contaminated feed. Spread within herds is facilitated by poor hygiene, particularly around calving and contamination of feed/water and the environment.

An effective plan to reduce risks of Johne’s infection in the youngest calves will have positive effects in reducing risks of Salmonella infection. Sick pens and calving pens should always be separate. Salmonella vaccination should be considered as part of the plan to reduce levels of infection and shedding by infected animals (Table 2).

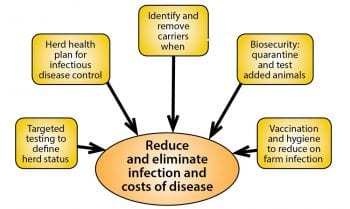

Endemic infectious diseases, such as BVD, IBR and Salmonella, in the national herd continue to have substantial economic and welfare implications. The first step in controlling these infections is knowing the herd status.

Once herd status is known, the information should be used to complete a herd health plan that targets either keeping infection out of the herd or reducing and eliminating infection, and resulting adverse economic effects over time.