15 Oct 2024

Owen Atkinson explores how data can be used by vets for reviewing and forecasting on farms.

Image © Anastasiia / Adobe Stock

Stress is not good for us. It shortens our lives, leads to “thinking errors” and is not a nice feeling.

On cattle farms, stressed cattle are more dangerous, they are less predictable, are more difficult to work with and, for them, too, it is not a nice feeling.

Stress might be defined physiologically by a rise in adrenaline or cortisol – the two stress hormones. Of course, stress has a biological and evolutionary function too. Adrenaline helps divert blood to our muscles so we can run away from danger faster, or fight more bravely. Cortisol helps raise energy resources (sugar) in our bodies, suppresses inflammation and increases our blood pressure – great when we are fighting off a bear, but not so great if we want to avoid heart disease or enjoy a long life.

In dairy herds, among other negative effects, high stress levels are associated with higher levels of lameness and decreased milk production (Hemsworth and Coleman, 2011).

Understanding how to avoid stress begins with understanding what causes it.

Cows, like us, have seven core emotions and affective feelings (Panksepp, 2004):

This is not the time or place to dwell too much on these, except to say that we experience these “core emotions” in our mid-brain. The associated feelings do not need thought or a developed cortex (our fore-brain) and, because our mid-brain architecture is almost identical, no reason exists to believe that other mammals – cows included – experience these feelings any differently to us humans.

Emotionally, all mammals are very similar; how we think and communicate is different.

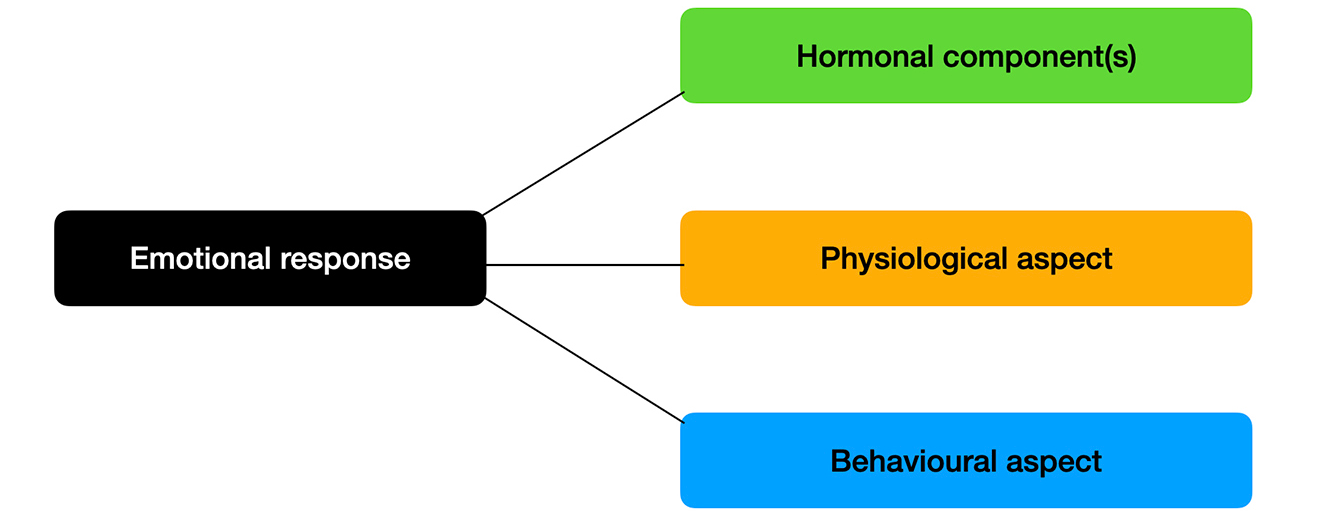

One of the standout things about the core emotions is that they are all associated with a hormonal component, a physiological component and a behavioural component (Figure 1). Take fear as an example: the hormonal component is adrenaline, the physiological component is raised heart rate and the behavioural component is freeze, flight or fight. Stress is essentially due to the emotional states of fear, panic or anger, all of which might see raised adrenaline and cortisol levels.

Figure 1. Emotions have a hormonal, physiological and behavioural response.

We do not always think straight when we are in a highly emotional state, and this is because our emotional mid-brain takes precedence over our rational fore-brain, which is a physiological and evolutionary reality of being an animal: hence the “thinking errors” caused by a rush of adrenaline and stress.

Luckily, the more positive emotional states of love, joy and seeking are antidotes to stress. Raising endorphins through a timely cuddle is a frequently used way to calm a stressed child, and is called “contact comfort”, a widely studied phenomenon common to mammals and birds.

In a similar way, soft talking, stroking and providing environmental enrichments (stimulating curiosity) are all effective ways to reduce stress in cattle.

But let us turn our attention to reducing stress due to fear and panic in the first instance. Four “big fears” exist for cows that we should be aware of:

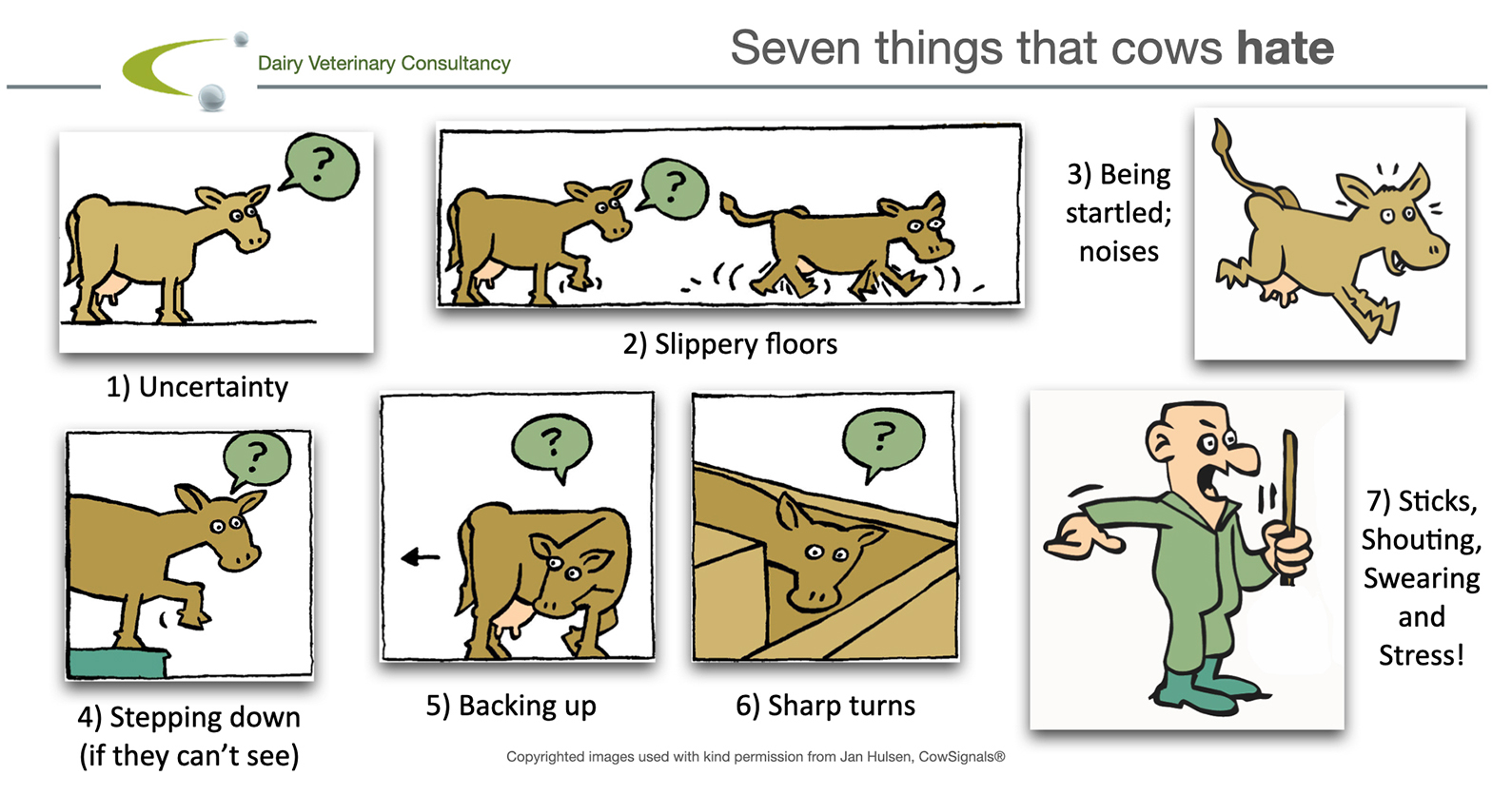

Figure 2 depicts seven things that cows really do not like; avoid these and you are halfway to a happier, stress-free herd.

Figure 2. A summary of seven things that cows hate, and that cause them stress.

Good stockperson skills can be taught and learned. While a lot of good stockpeople exist, it is a dangerous assumption to credit everyone who works with cattle with a natural ability to move cows in the best possible way.

The first rule is to recognise that stress free handling only works in the absence of adrenaline. The second rule is to recognise that fear (and stress) spreads.

Once adrenaline levels rise, it takes around 20-30 minutes for levels to subside. That is the time to go and have a cup of tea, and come back to the task in hand only when the cattle (and people) have calmed down.

So, working in a low-stress state, a stock person can use a few nice techniques to move cows, and get them to go calmly where they want them to go. The “pressure point” and “balance points” are used.

Cows experience the world differently to us, as they have different eyesight, hearing and smell. An awareness of how the cow senses her environment is important; for example, they do not judge distances too well, yet have a wide field of view; they can hear us approaching from a long way away, yet are very sensitive to strange or loud noises; they can smell fear (probably), yet cannot discern a shadow on the ground from a bottomless pit they are about to step into.

“So, working in a low-stress state, a stockperson can use a few nice techniques to move cows, and get them to go calmly where they want them to go.”

Imagine that every cow has a “personal space” around her, known as the “flight zone”. When we step into this zone (slowly, normally, without inducing fear), she will have a tendency to turn or move away. For most dairy cows, this is around one to two metres radius around her. For beef cows, less used to human contact, it will likely be four to five metres.

The exact edge of the flight zone is called the “pressure point”. We can use this to “press and release” – this is moving our bodies into the pressure point to induce the cow to move and then backing off to reward her movement.

A zig-zag walk, or wiggling our whole body, helps the cows to judge where we are and to recognise when we are backing off.

For turning the cow left and right, or for start-stop, we can use the two balance points of a cow. One balance point is the straight line from nose to tail. Position ourselves slightly to the left, and the cow goes right, and vice versa. The second balance point is the point of the shoulder. Position ourselves behind this and the cow moves forwards; position ourselves just ahead of the shoulder and the cow stops.

She will not go backwards (because cows do not like doing reverse gear) unless a lot of pressure is applied. Be happy with go/stop.

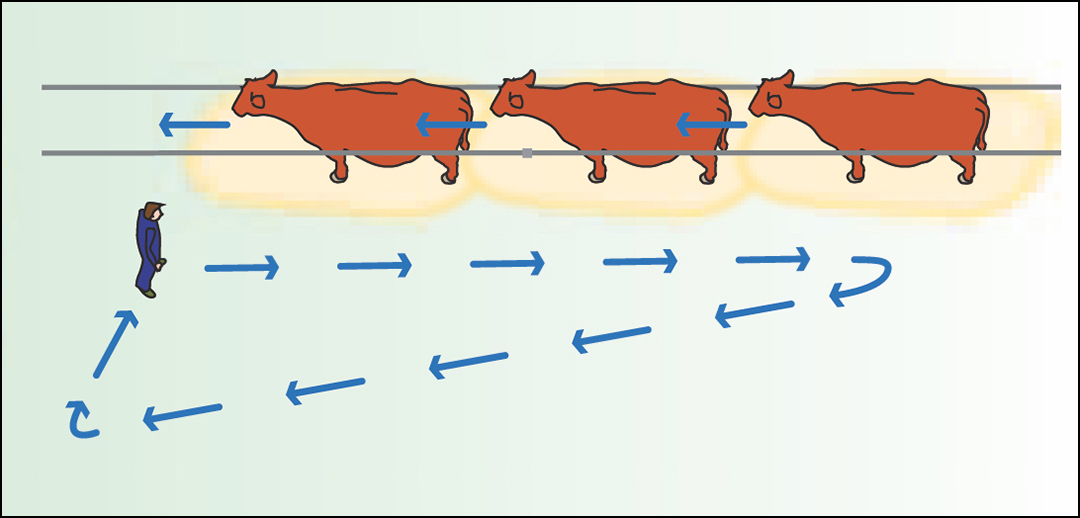

Figure 3. Walking in the opposite direction to move cows forwards in a race.

Quite frequently, we try to move cattle along a race. Applying pressure to the rear cow does nothing to move the front cow, and cows are great followers. The correct technique to use here is simple: if the herdsperson walks from the front of the row to the back, passing the points of the shoulders as they do so, and within the pressure point, the whole row will walk steadily forwards.

To keep the column of cows moving, come out of the flight zone and move to the front of the column to repeat the process. This is called “parallel reverse walking” (Figure 3).

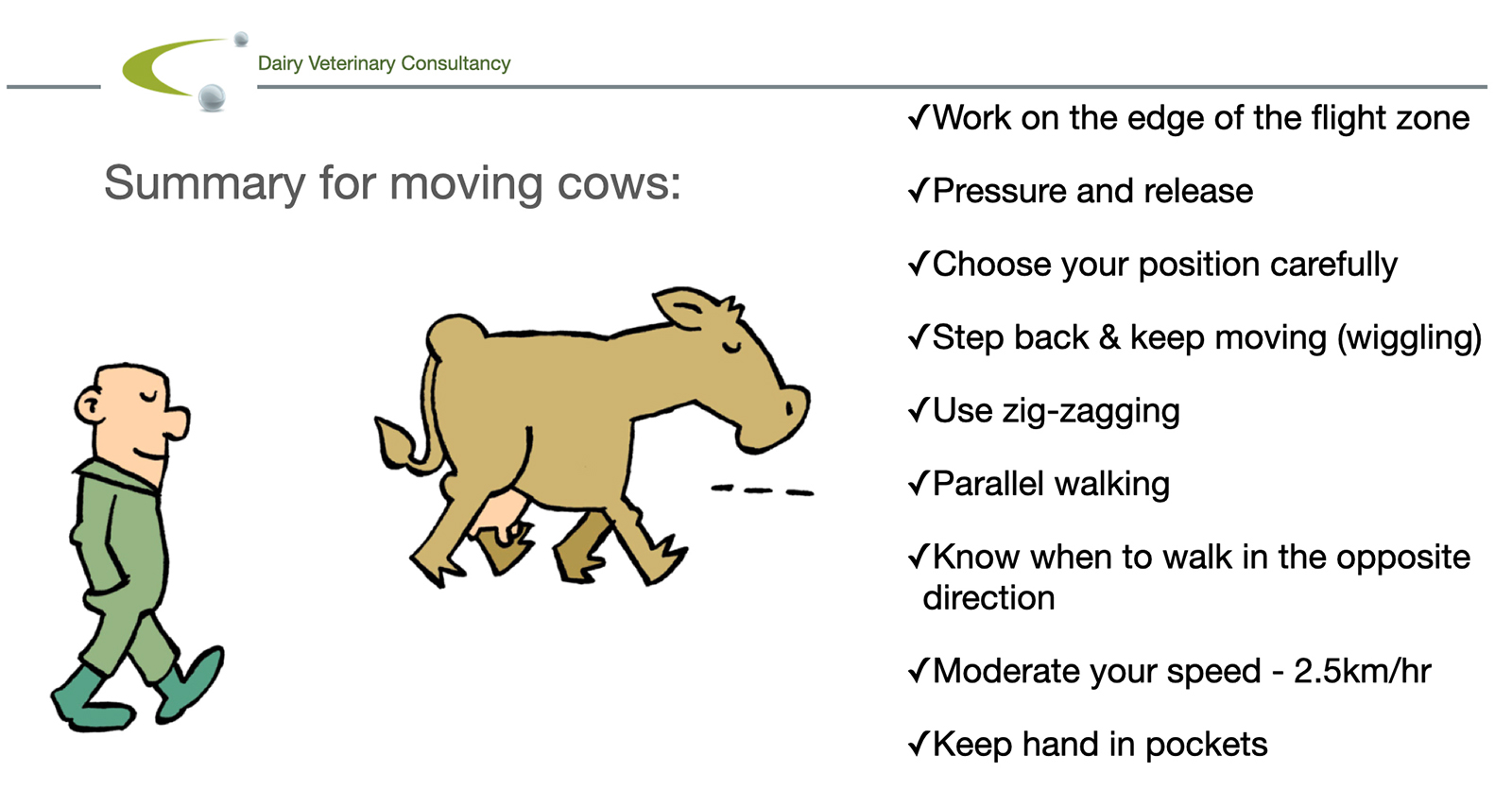

Many advantages to practising stress-free handling exist; Figure 4 summarises some of the techniques.

Being aware of one’s own state of mind is possibly the most important aspect to all of this. A happy person behaves in a happy manner and tends to be calm, quiet and relaxed when working with cattle. The cows respond well to this and are well behaved. This leads to a positive feedback loop: a greater enjoyment for working with cows and an increase in one’s own personal happiness.

Figure 4. Summary for moving cows with low stress.

On the other hand, a stressed or unhappy person tends to be more abrupt, move quicker and raise their voice more. The cows respond by being fearful, acting unpredictably and being far less pleasurable to work with.

Ask, “how much do I enjoy my job and working with cows?” – if the answer is “not very much”, then maybe it is time to choose an alternative avenue of work.