16 Oct 2017

Natasha Mitchell discusses various ocular diseases affecting dogs that are seen in veterinary practice, as well as treatment strategies.

Figure 1. Entropion of the lateral aspect of the lower eyelid in a 15-month-old male great Dane with associated corneal ulceration staining positively with fluorescein dye and conjunctivitis.

A wide range of ocular conditions are seen in canine practice, the most common of which include corneal ulceration, conjunctivitis and keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS).

Corneal ulceration is a frequently encountered problem in small animal practice. It is defined as a break in continuity of the corneal epithelium, with or without loss of underlying corneal stroma. It has multiple possible causes and the most suitable treatment varies depending on the type of ulcer present.

Causes include:

Clinical signs include pain (blepharospasm and increased lacrimation) and focal corneal oedema due to epithelial loss. Ocular discharge may become mucopurulent or purulent, and corneal neovascularisation may occur.

A basic work-up for a case of corneal ulceration should include a Schirmer tear test (STT), assessment of the palpebral and corneal reflexes, careful examination of the eyelids, conjunctiva and nictitans, and staining with fluorescein dye. Exposed hydrophilic stroma uptakes the dye, while intact epithelium and Descemet’s membrane does not (Figure 3).

A tendency exists for fluorescein dye to pool in the depression in the corneal surface, so excess dye should be gently flushed from the ocular surface with sterile saline. Microbiological assessment – including surface cytology, and bacterial culture and susceptibility testing – is recommended for deep or melting corneal ulcers. The type of corneal ulcer is determined from its depth, location and extent, and then classified as superficial, stromal, descemetocoele, perforated or melting.

Treatment depends on the extent of the ulcer and the presence or absence of complicating factors, such as adnexal defects, tear film deficiency, infection or melting. If the underlying cause is identified, it should be specifically corrected.

Ulcers are treated with a topical antibiotic to treat or prevent infection. First line antibiotics, such as 1% fusidic acid, are used for Gram-positive infections with Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus intermedius or topical gentamicin when Gram-negative infection is suspected, although the latter does also have some spectrum of activity against Gram-positive bacteria. Of those medications, only one is specifically licensed for treatment of corneal ulcers in dogs. Antibiotic use in more complicated ulcers is discussed further on.

Systemic antibiotics are used in cases of corneal perforation, melting or very deep ulcers. Secondary uveitis should be controlled if it is present, while topical mydriatics are used if the pupil is constricted. Systemic NSAIDs are suitable for both treatment of uveitis and some degree of pain relief. Pain should be minimised – this may be achieved through oral NSAIDs, when appropriate, occasionally oral opioids and topical mydriatics when uveitis is present.

Topical artificial tears will aid comfort if the eye is dry or has frictional irritation. Formulations containing hyaluronate have increased retention time. Otherwise, topical antibiotics are sufficient for simple corneal ulcers and anticollagenases are more important than artificial tears in deep or melting ulcers. A therapeutic soft bandage contact lens and a third eyelid flap can reduce pain when their use is appropriate.

Self-trauma should be prevented, so an Elizabethan collar is used if necessary. In cases of melting, anticollagenase treatment is needed (see further on). Surgical treatment is usually required for deep ulcers with significant stromal loss, corneal perforation and sometimes melting ulcers. This is also discussed further on. Just as importantly, advice on what not to do for corneal ulcers should be noted:

Superficial corneal ulcers have absent epithelium, but the underlying stroma is intact. Causes can include trauma, KCS, exposure keratitis, glaucoma and uveitis. Simple, uncomplicated ulcers should heal quickly – in a few days. A broad-spectrum topical antibiotic is indicated, usually two to three times daily.

Non-healing chronic superficial ulceration has many synonyms, including SCCEDs, boxer ulcers and indolent/refractory superficial ulcers. The definition of an SCCED is a chronic epithelial erosion that fails to heal through the normal wound healing process.

It is characterised by the presence of a loose, non-adherent lip of redundant epithelium at the edges of the defect (Figure 4). This occurs due to impaired epithelial adhesion to the underlying stroma. Variable corneal neovascularisation, oedema and pain occurs and they can persist for several months. The syndrome typically occurs in older animals (7 to 10 years old) and boxers are over-represented, although it can occur in any breed of dog.

SCCED treatment focuses on removing the redundant corneal epithelium (by debridement) and wounding the underlying stroma to encourage effective healing. This is achieved by grid or punctate keratotomy, diamond burr keratotomy, or a superficial keratectomy if all else fails. Medical treatment is also used, but debridement is key to rapid healing.

The equipment required for debridement and grid keratotomy is topical anaesthetic, sterile dry cotton swabs and 25-gauge needles. All cases of SCCED (not deep, infected or melting ulcers) in dogs benefit from debridement of the redundant loose epithelium.

After applying topical anaesthetic (with light sedation if necessary; deep sedation will cause the eye to roll ventrally), a dry cotton bud is applied to the ulcer and firmly pushed radially outwards in all directions, thus pushing off any epithelium that is not adherent. Sometimes this results in removal of the entire corneal epithelium. A grid or punctate keratotomy is then performed, starting in the healthy corneal epithelium. The needle penetration needs to be just deep enough to wound the underlying stroma and provide a foothold for the new migrating epithelium, but not too deep (Figure 5). The use of diamond burrs has greatly increased as an alternative to grid keratotomy – they are relatively easy to use and results are encouraging.

A soft bandage contact lens may be placed after debridement, but is not suitable for a deep or melting ulcer. Lenses come in various diameters and curvatures, and will not stay in place unless the correct lens is chosen.

In dogs with macropalpebral fissure, a temporary lateral tarsorrhaphy may hold them in place for longer. They stop any irritation from eyelids or hairs, spread the tear film evenly over the cornea, increase the temperature of the cornea – which creates a healing environment – and provide comfort. The debrided eye is then treated with a topical, broad-spectrum antibiotic to prevent infection, usually two to three times a day.

A single drop of topical atropine is applied. Serum and doxycycline may aid treatment and are certainly not contraindicated, but are usually used for deep or melting ulcers.

Artificial tears lubricate and soothe the cornea. An Elizabethan collar may be provided if the animal is rubbing at the eye.

Dogs with SCCED are typically re-examined 10 to 14 days later. At this stage, it is expected the ulcer should be healed and, therefore, the cornea should be fluorescein negative. If not, debridement may need to be repeated. A third eyelid flap is not contraindicated and may aid healing; however, it does not seem to be necessary. Occasionally, a superficial keratectomy is required, which has very good success rates.

Stromal ulcers involve loss of the outer corneal epithelium, along with some of the underlying stroma (Figure 6). A descemetocoele occurs where complete focal loss of the epithelium and stroma is present, with only Descemet’s membrane and the corneal endothelium intact.

Fluorescein does not stain Descemet’s membrane, so the absence of stain uptake at the base of a corneal ulcer, along with positive uptake in the walls of the defect, should prompt a diagnosis of a descemetocoele, which is a genuine surgical emergency.

Any eye affected by corneal ulceration should be assessed for secondary reflex uveitis, which occurs due to stimulation of sensory nerve endings of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve within the cornea. Signs of reflex uveitis include miosis, aqueous flare and hypotony (Figure 7).

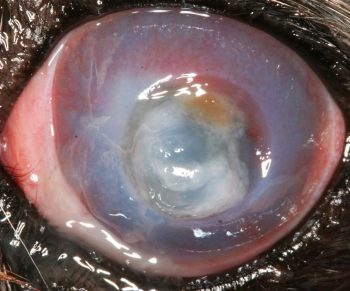

Liquefactive corneal necrosis, or corneal melting, is a very serious potential complication of all forms of corneal ulceration. It occurs following liberation of collagenase enzymes from invading microorganisms, white blood cells or keratocytes, which cause rapidly collagenolysis and loss of corneal structure. The cornea may appear white, cream or yellow due to infiltration of the corneal stroma with white blood cells and also due to corneal oedema. The smooth contour of the cornea is interrupted to a varying degree by liquefaction and the affected cornea loses rigidity and may appear to ooze ventrally (Figures 8 and 9).

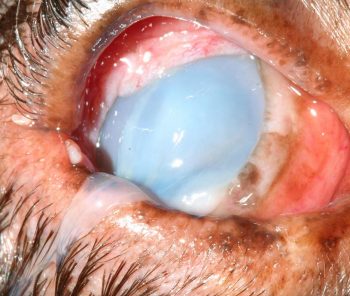

Rapid progression to corneal perforation can occur; therefore, this condition is an ophthalmic emergency. Treatment depends on the extent and depth of the ulcer and the presence or absence of complicating factors, such as infection, melting or corneal perforation – usually with iris prolapse (Figure 10).

Deep, melting and perforated corneal ulcers require prompt and intensive treatment, and referral should be considered. If a risk of self-trauma exists, an Elizabethan collar should be fitted. An appropriate topical antibiotic is chosen – preferably based on examination of cytological specimens initially, although this may need to be altered on receipt of any pending culture and susceptibility tests.

Chloramphenicol is a suitable first choice for infections of Gram-positive cocci, whereas gentamicin or ofloxacin are appropriate initial choices for infections with Gram-negative rods. The frequency of application of topical antibiotics varies according to clinical presentation and the results of laboratory testing, but should initially be every one to two hours in cases of corneal melting.

Systemic antibiotics are generally indicated. Doxycycline is a good choice as it also inhibits matrix metalloproteinases that can cause melting. Anticollagenase medication is also essential in the case of melting ulcers, and autologous serum is most commonly used – again, initially every one to two hours until stabilisation is achieved.

Secondary uveitis is always present, so topical treatment with atropine 1% is indicated to effect (to maintain dilation of the pupil), but usually no more than once daily for up to three days. Contraindications to atropine use include raised intraocular pressure and KCS.

Systemic NSAIDs are useful to reduce ocular pain and help stabilise the blood-ocular barrier. Frequent re-examination will be essential during the early stages of medical treatment to ensure the ulcer does not become deeper or get infected, or the globe does not rupture.

Surgical repair with a graft, such as a conjunctival pedicle or corneoconjunctival transposition, should be considered for ulcers greater than one-third of the stromal depth. Surgery may also be required for melting ulcers, to remove necrotic corneal tissue and stabilise the cornea.

Corneal collagen cross-linking has been reported as a successful treatment for infectious and non-infectious corneal melting in dogs and cats. It involves using riboflavin as a photosensitiser, followed by exposure to UVA light. The result is an increase in the biomechanical stability of the cornea, and also in reactive oxygen species-induced damage to any microorganisms in the irradiated area. Availability of this treatment modality is likely to increase in the near future.

Conjunctival autografts can be used to manage deep corneal ulcers, descemetocoeles and keratectomy sites. Bulbar or palpebral conjunctiva with intact epithelium and underlying fibrous tissue, blood vessels and lymphatics is sutured into the defect to provide tectonic support and promote healing.

Several different types of conjunctival grafts may be used to reinforce a weakened cornea, including the conjunctival island, 360° conjunctival, conjunctival hood, conjunctival bridge, conjunctival pedicle and corneoconjunctival transposition (CCT) grafts.

The most commonly used techniques are the conjunctival pedicle and the CCT grafts. Technical expertise, microsurgical instrumentation and magnification – preferably with an operating microscope – are required.

Conjunctivitis is inflammation of the conjunctiva. Clinical signs always include hyperaemia, but may also include ocular discharge, chemosis, conjunctival thickening or ulceration, subconjunctival haemorrhage and follicle formation. It may be classified according to:

The cause is the most useful classification and should be determined wherever possible. In dogs, conjunctivitis is most often secondary to adnexal abnormalities or KCS. An aetiological diagnosis is not always possible to determine, even though it is one of the most common ophthalmic problems encountered in practice, because the clinical appearance is quite non-specific and it may be self-resolving.

Possible causes include:

Treatment requires identification of the underlying cause so appropriate management can be implemented. KCS treatment is discussed further on. Conjunctivitis, as a result of an adnexal abnormality, tends to resolve once successful surgery is performed. Infectious causes are treated with topical antibiotics, employing the cascade and ideally culturing the pathogen to determine the most effective medication. Topical steroids may be used for inflammatory and immune-mediated conjunctivitis, and help with allergic conjunctivitis. Chronic conjunctivitis can lead to KCS or entropion, so ongoing monitoring is advised.

KCS is a common and potentially blinding disease. A quantitative deficiency of the aqueous component of the tear film causes drying of the ocular surface (cornea and conjunctiva), resulting in inflammation. Signs include conjunctivitis, keratitis, purulent tenacious ocular discharge (often misinterpreted as pus/infection), blepharospasm and general ocular discomfort, corneal neovascularisation and/or pigmentation (Figures 16 and 17).

Neurogenic dry eye arises due to damage to the parasympathetic portion of the facial nerve, which is often unilateral and presents with an ipsilateral dry naris (Figure 18).

An STT of 10mm/min or less, in conjunction with clinical signs, confirms the diagnosis. STT readings of 10mm/min to 14mm/min are suggestive of the condition, and the test should be repeated in the near future, with use of artificial tears in the meantime.

KCS treatment should be started promptly before more permanent corneal changes develop, and will be required for life (except in some cases of neurogenic dry eye), which should be emphasised to the owner at the outset. A topical immunosuppressant is required for KCS, and 0.2% ciclosporin is the mainstay of treatment, suppressing the immune-mediated attack on the lacrimal glands.

A lag phase occurs before the full benefit is seen, and it can take four to six weeks to reach maximum benefit. Therefore, treatment should not be stopped for at least this period of time, and artificial tears should be used to supplement the tear film in the early days. It generally works well, though does have less of a benefit when the tear readings are very low.

Tacrolimus (0.03% in oil or 0.03%/0.1% dermatological ointment) can be used in refractory cases. It is not licensed, so owners must be made aware of this. Episcleral silicone matrix ciclosporin implants have been used with some reported success. This would be particularly useful when topical medication is not possible, such as with a fractious dog.

Pilocarpine eye drops may be used in the case of neurogenic dry eye at a dose of two drops of 2% solution orally twice daily for every 10kg. It can also be used topically at a 0.1% concentration, as denervation hypersensitivity is present.

Topical steroids could be considered to reduce neovascularisation and as an additional immunosuppressant. However, dry eyes are more prone to corneal ulceration and steroids are contraindicated in this situation.

Topical antibiotics will reduce bacterial overgrowth, but are not required long term. The purulent discharge is not due to bacteria, but usually to the high levels of mucins and inflammatory cells.

Surgical treatment with a parotid duct transposition is an alternative carried out a lot less commonly than it used to be, due to the success of ciclosporin. The surgery involves rerouting the duct of the parotid gland to the conjunctival sac so saliva will moisten the globe. It is still an appropriate treatment in cases unresponsive to medical treatment.