25 Sept 2017

Peter Bates looks at the workings of this method of ectoparasite control in sheep and how it has changed over the years.

Plunge dipping has been the principal method for sheep ectoparasite control worldwide for more than 150 years and used in two sheep scab (Psoroptes ovis) eradication campaigns in Great Britain.

Scab was made a notifiable disease in Great Britain and Ireland in 1869 and – after 78 years of compulsory dipping in formulations containing arsenic, sulphur or coal tar – was far from eradicated. These dips did not protect sheep from reinfestation and were not ovicidal.

Consequently, sheep had to be dipped again after 14 days to kill hatching larvae. Scab was eventually eradicated in 1952, after a further six years of compulsory dipping in formulations containing organochlorine lindane (γ-benzene hexachloride), which offered an effective cure and protection after a single dip.

In the following 20 years, lindane continued to be widely used for blowfly, ked, lice and tick control, but cyclodiene insecticides (aldrin, dieldrin and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) were also widely available. These continued to be administered by plunge dipping, but spray race and shower administration was also popular.

However, these alternative cyclodienes were not effective against scab and, along with their considerable ecotoxic effects, had been withdrawn from use when scab returned to Great Britain in 1973. Lindane via showers or spray races was shown to be ineffective against scab; consequently, only administration of lindane via plunge dipping was allowed when a second scab eradication campaign, also based on compulsory dipping, was instigated.

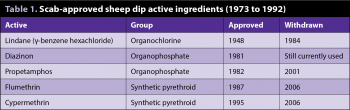

During both campaigns, dip formulations had to gain government approval and a marketing authorisation (MA). Initially, lindane was the only scab-approved plunge dip active ingredient available, with more than 90 dipping formulations available in 1973, but only the progenitor formulation manufactured in 1947 underwent approval testing (according to the protocol of the time). All others were approved “by right” – all they had to do was contain lindane. Lindane’s monopoly continued for the next eight years until the first organophosphate (OP)-based dipping formulation, containing diazinon, was scab approved in 1981.

In the following years, the OP propetamphos and synthetic pyrethroid (SP) flumethrin were scab-approved in 1982 and 1987, respectively (Table 1). Lindane dips were withdrawn in 1985 due to meat residue issues. Despite these very effective dips, the second campaign was deemed unsuccessful and the disease was deregulated as notifiable in 1992, and scab approval and supervised compulsory dipping ceased. Cypermethrin dips became available the year scab approval was no longer required.

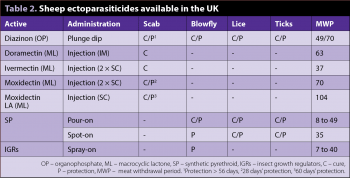

Unsupervised dipping continued, but deregulation prompted use of alternative ectoparasite control methods, such as systemic macrocyclic lactone (ML) injections and SP or insect growth regulator pour-on treatments (Table 2). These offered mobile, labour-saving alternatives to dipping that were less stressful to sheep, relatively safe to the operator and environment, and had apparent ease of use.

However, compared to plunge dipping, most have relatively narrow spectrums of efficacy – some require repeat treatments, while others offer no residual protection against re-infestation by P ovis or chewing lice (Bovicola ovis) and some have extremely long meat withdrawal periods (MWPs; Table 2).

The ML injections are also widely used as anthelmintics, and the increase in anthelmintic resistance in sheep gastrointestinal (GI) roundworms is a serious problem for the sheep industry. A survey of Welsh flocks by Hybu Cig Cymru (2015) found 83% were resistant to the white (benzimidazole) drenches, 67% to the yellow (levamisol) drenches and 29% to the clear (ML) drenches. The overuse of ML injections for the control of P ovis could easily select for or augment existing resistance to MLs in non-target GI roundworms. Plunge dipping is an effective alternative for the control of P ovis and other sheep ectoparasites, having no effect on GI roundworms. Disadvantages exist (Panel 1), but these can be effectively circumvented using a mobile dipping contractor.

Advantages.

Disadvantages1.

1. Can be reduced by using a mobile dipping contractor.

In 1995, three years after scab deregulation, the landscape of ectoparasite control in Britain began to change. Of the 22 available sheep ectoparasiticide products with an MA, only 14 (67%) were plunge dips (containing diazinon, propetamphos, flumethrin or cypermethrin).

An amidine dip (containing amitraz) was also available, but had no efficacy against scab or blowfly strike. Of the alternative methods available, pour-on/spot-on formulations accounted for 23% and ML injections 9% – both based on ivermectin. Twenty years later, a similar number of ectoparasiticide products were available, but plunge dipping accounted for only 9.5%, consisting of two diazinon formulations. The remaining 80% consisted of 47.6% pour-ons/spot-ons and 42.9% ML injections (containing either ivermectin, doramectin or moxidectin). Plunge dipping had dramatically fallen out of favour.

A possible dipping decline reason is human toxicity issues. During the second eradication campaign (particularly between lindane withdrawal in 1985 and flumethrin approval in 1987) sheep farmers, their families, dipping contractors and hired helpers were regularly exposed to OP dip via compulsory dipping.

Although exposure to low concentrations – via contact with made-up dip wash or dipped sheep – can affect health, the principal danger was direct contact with the pre-diluted concentrate. In 1993, the purchaser and/or user of OP (or SP) dip in the UK had to gain a National Proficiency Tests Council Level 2 Certificate of Competence in the Safe Use of Sheep Dips, awarded through a local agricultural college.

In 2000, all OP formulations were withdrawn in Britain for manufacturers to improve their delivery systems, minimising contact with OP concentrate. SP dips continued to be available. In 2001, it became a legal requirement to use a closed transfer system (CTS) when measuring out and mixing OP concentrate, thus reducing direct contact. Only diazinon dip formulations, with an effective CTS (or pre-measured volumes of concentrate in water soluble bags), reappeared on the UK market.

It is extremely important that an ectoparasite is accurately identified and the correct treatment advised. Incorrect treatment may be ineffective, continuing the suffering of infected sheep. Repeat treatment would be necessary, increasing the time for disease resolution – which, together with additional MWPs, could affect the financial potential of animals intended for the food chain. Also, inappropriate ML administration could select for ML resistance in non-target GI roundworms.

Semi-permanent ectoparasites have one or more free-living stages, actively seeking a new host – for example, in blowfly strike only the larvae are parasitic. Treatment is, therefore, usually preventive, occurring prior to an expected attack. Permanent ectoparasites (for example, P ovis) are all obligate parasites with no free-living stages in the environment.

If forced off the host, they cannot survive more than 17 days and will not actively seek a new host. Transfer between hosts is always passive, through direct sheep-to-sheep contact or, to a lesser extent, parasites deposited in the environment. Treatment is, therefore, largely curative, with an element of protection from ectoparasites in the environment. However, treatment can also be preventive; sheep treated prophylactically if they are known to mix with actively infested animals – for example, on common grazing.

A scab treatment has to remain active in/on the sheep longer than 17 days to prevent reinfestation. If not treated, animals must be moved to grazing or housing that has not held sheep for at least 28 days. Sheep treated with a product that offers protection can remain in or on the same housing or grazing without any risk of re-infestation.

Part of the old dip approval protocol was that sheep with 1cm of fleece, dipped for one minute in the maintenance concentration (MC; Figure 1) of the test product, must protect against (re)infestation by P ovis. The required period of protection prior to 1982 was 56 days, between 1982 and 1988, 28 days and after 1988, it was 21 days.

Field studies have shown diazinon dipwash, made-up and replenished according to the label instructions, is guaranteed to give 21 days’ protection against sheep scab on both unshorn sheep or sheep with 1cm to 1.5cm of fleece. However, all unshorn sheep and 75% of recently shorn sheep remained protected for eight weeks or more.

A dipping facility consists of collecting pen(s), the dip bath and the draining pen(s). The dip bath and draining pens can also be mounted on a trailer or lorry and used by mobile dipping contractors. Dip baths are usually home-made using rendered concrete or manufactured in galvanised steel or fibre glass, with a capacity to hold 900L to 2,250L (200 gallons to 500 gallons) of dip wash. It is important the volume is accurately known, and can be determined with a water meter or by counting the number of containers of known volume to fill the bath to its working level, which must be marked on a calibration stick (never on the side of the bath). The working level should comfortably hold the intended volume of dip wash, plus the correct number of sheep to be immersed without any overflow.

Dipping formulations are all emulsifiable concentrates binding to a carrier substance – usually oil-based – which, together with an emulsifier (similar to detergent), aid in the formation of microscopically small droplets of ectoparasiticide in an emulsion.

When added to water, the emulsifier causes the ectoparasiticide complex to disperse uniformly throughout the water and, when mixed, gives the dip wash its milky appearance. Mixing must be for at least five minutes to disperse the droplets uniformly. Each sheep must be introduced to the dip wash slowly, against the lie of the fleece, and must be kept moving in the bath to displace air and allow for maximum penetration.

It is essential, for the control of all ectoparasites, immersion is for one minute, with 50% less diazinon absorbed after immersion for only 20 seconds and 38% less after 40 seconds. Dipping for under one minute can result in a 60% failure to cure active scab. Manipulation of sheep in the dip bath is carried out by an operator standing to one side, or on a central island in the case of circular dip baths. Splash boards are provided, to prevent splashing, with safety rails to prevent accidents. Splashboards and rails must not inhibit effective sheep manipulation, which is via a dipping crook attached to a long (metal) pole. The majority of the dip bath is wide and deep enough to allow effective immersion.

At the end – furthest away from the entry point – a gradual, ridged slope allows easy exit of the dipped sheep. The flow of sheep through the dip must be regulated. If too many sheep are dipped at one time they may not all get fully immersed, with the shoulders (a major site for scab lesions) not dipped effectively. Scab mites can reside in the ear and the infra-orbital fossae; consequently, the head has to be immersed twice during dipping, usually as the sheep enter the bath and as they leave.

Plunge dipping was once thought to work through the mechanical sieving or filtering of the dip emulsion as the sheep drained, retaining ectoparasiticide and returning dip wash, weaker in concentration, back to the dip bath. However, diazinon formulations are highly lipophilic and are preferentially absorbed into the skin/wool grease while the sheep are in the dip bath, the concentration of diazinon in the run off not differing significantly to that simultaneously in the dip-bath (Figure 2). Absorbed diazinon is concentrated in the wool/skin grease (around 3,189mg/L) compared to that simultaneously found in the dip wash (around 276mg/L).

Each sheep takes out 18L to 32L (4 gallons to 7 gallons) of dip wash (depending on size, breed and fleece length), retaining 1L to 4.5L (0.25 gallon to 1 gallon) in the fleece. A total of 100 sheep can, therefore, remove between 100L and 450L of dip wash. Consequently, the volume of the dipwash will fall and the concentration of diazinon becomes progressively weaker as successive sheep pass through (“stripping” or “depletion”). Consequently, the wash has to be “replenished” through the addition of diazinon concentrate (traditionally at 1.5 times the IC) at set intervals throughout dipping to maintain an effective concentration. Water also has to be added to maintain the original working volume.

Three critical dip wash concentrations are recognised (Figure 1):

All available diazinon dip formulations are replenished after a defined number of sheep (head count method). As dipping progresses, dip wash becomes progressively fouled with organic matter (such as soil, faeces, fleece and kemp), providing a substrate for the preferential absorption of diazinon, rendering it unavailable for fleece uptake. Replenishing with diazinon at a higher concentration compensates for this.

Dip wash can be fouled by 3% to 5% organic matter at the end of dipping, with 5% fouling leading to 60% less fleece uptake of diazinon compared to clean dip wash. Consequently, the entire dip wash should be discarded after one sheep per 1.5L (3 sheep per gallon) of the initial volume of dip wash (after 600 sheep for 200 gallons/900L).

Fouling can be reduced by thoroughly cleaning the dip bath before use and dagging all sheep before dipping. Collecting pens and races leading to the dip entry should be made of rough concrete or slats to remove dirt/faeces from the feet and thoroughly cleaned before dipping. Throughout dipping, the collecting and draining pens must be swept regularly, and kemp, fleece and faeces skimmed off the dipwash before each replenishment.

Sheep leave the dip bath into the draining pen(s), where they should stand for at least 10 minutes after dipping, allowing excess dipwash to drain off and return back into the dip bath. Consequently, the floor of the draining pens should be impervious, laid on a slope to direct any drainage back to the dip bath, normally via a trap to filter out solid matter. It is advised not to dip in the rain. Heavy rain can add significant volumes of water to the dipbath via the draining pens, consequently diluting the dipwash to unknown concentrations.

A fleece length of at least 1cm is essential for effective dipping, with better penetration to skin level and absorbing the same concentration of diazinon (w/w) as a full fleece: lengths of 1.5cm, 3.1cm and 5.8cm retaining 3,456, 3,271 and 3,468 diazinon (mg/L) respectively. As the fleece grows (about 1cm a month), the diazinon is soon diluted.

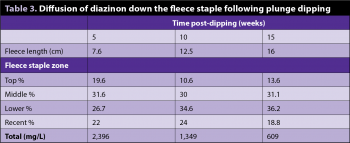

Winter dipping of full fleeced sheep not only cures scab, but also gives considerably longer periods of protection. Diazinon diffuses down the wool fibre via the wool grease, eventually reaching new wool growth next to the skin, the relative proportions of diazinon in the top, middle, lower and recent growth sections of the wool staple remaining constant with time (Table 3). Recent growth arising from the skin continuously absorbs diazinon and, thus, P ovis and B ovis close to the skin can be continually exposed to fresh diazinon.

As soon as diazinon is absorbed into the wool/skin grease, it begins to degrade, via sunlight and rain, with the highest concentrations occurring within the first few weeks of dipping. Although sheep with 1cm to 3cm of fleece take out more diazinon initially, the rate of degradation is quicker, retaining 35% to 51% 28 days after dipping, compared to 53% to 77% for unshorn sheep.

However, 56 days after dipping, the values are almost equal, ranging from 25% to 28% diazinon retained. Light or heavy rain within three weeks of dipping can wash out 8% or 12% diazinon, respectively, and sheep washed or bloom dipped within two weeks of dipping can also seriously reduce the fleece diazinon concentration.

Another reason for the apparent plunge dipping decline is environmental safety. Historically, spent dip wash was released directly into the environment – usually on land within the direct vicinity of the dip bath, which, in itself, was traditionally near a watercourse the water was sourced from. If the dip facility was on a hill, a plug was pulled and the used dip wash ran down the hillside. Pollution was inevitable.

In 1991, it became an offence to pollute waterways/groundwater with OP/SP dip wash and, in 1999, disposal of spent OP/SP dip wash on agricultural land required the purchase of an authorisation from the Environment Agency or the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency. SP formulations were considerably more toxic to the environment than OPs (which break down relatively quickly in soil). Consequently, all SP dip formulations were permanently removed from the UK market in 2006.

Newly dipped sheep should not be turned out on a field that has direct access to a water course. Dipped sheep must stand in the draining pen for at least 10 minutes and not return directly to their normal grazing, but held in a holding field (with a trough of fresh water, but no access to natural water courses) next to the dipping setup for a minimum of 24 hours, allowing sheep to dry out before moving on.

If natural watercourses exist in the holding field, they must be fenced off from livestock access. Dipped sheep should never be allowed to ford a water course.

Following scab deregulation in 1992, sheep showers became popular again – primarily to circumvent dip disposal charges. Showers submit sheep to a deluge of ectoparasiticide wash, aiming to soak the entire fleece to skin level, and are considered more “eco-friendly”, with only a few litres of wash remaining after treatment (usually poured back over the treated sheep), as opposed to up to 2,250L (500 gallons) for plunge dipping.

Shower units consist of a circular (or rectangular) enclosure into which sheep are herded, with fixed sprays on the floor to wet the underside, but most saturation is achieved through nozzles attached to a horizontal rotating boom above the sheep (Figure 3).

Ectoparasiticide wash is pumped at a high rate (for example, 400L/min) from a tank, through the nozzles and excess run-off drained back into the tank and recycled. In the UK, showers are generally lorry-mounted and mobile, and holding 10 to 15 sheep at a time (depending on size). The basic principles of plunge dipping also apply to showers – particularly the importance of the IC, MC and MLC, and the theories and practices of replenishment.

In the UK, no product is licensed for use through a shower, and diazinon plunge dip formulations are only licensed for use according to the manufacturer’s instructions (that is, plunge dipping), with no instructions regarding showers – particularly information regarding depletion and replenishment.

Showers were first used in New Zealand in 1905 and have been used for lice and blowfly control in Australia and New Zealand since the 1950s. Their main disadvantage is the question over efficacy against scab. Scab was eradicated from Australia in 1896 and New Zealand in 1885; consequently, no information exists regarding their use to control this ectoparasite.

Unlike the recommended one minute for plunge dipping, no standard time exists for showering sheep for full saturation. This is dependent on wool length, body size, breed and the efficacy of the shower unit, which, in itself, is dependent on setup, calibration and maintenance (engineering factors), and accurate make-up and maintenance of the dipwash (chemical factors). The latter is deduced by “educated guesswork”, as this is not on the product data sheet. For this reason, many shower operators treat sheep for varying times, with little standardisation.

In Australia, the advised time for full saturation is a minimum of eight minutes (six minutes from the top jets, two minutes from the bottom jets). In the UK, the advised time for showering, using a Monsoon Shower Unit, is 2.5 minutes top boom and 0.5 to 1 minute from the bottom jets. Plunge dipping for one minute fully saturates an entire, full-fleeced sheep to skin level, with between 336mg/L and 6,960mg/L diazinon in the belly wool, compared to only 36mg/L and 410mg/L after showering.

Fleece length is an important limiting factor in dipwash penetration. Scab mites (P ovis) and chewing lice (B ovis) live on or close to skin. Consequently, they will only be killed if saturation is to skin level.

Diazinon, via shower, has been shown to be 100% effective in eradicating P ovis infesting short (1cm) fleeced sheep. However, the function of a full fleece is to prevent wetting to skin level by cold, winter rain. Consequently, it is difficult to deliver ectoparasiticide to skin on full-fleeced (winter) sheep – the peak of scab and lice cases. Exposure of scab mites to sub-lethal concentrations of diazinon via ineffective shower (or plunge) dipping may select for diazinon resistance.

This will increase use of ML injections for scab control, significantly increasing the selection pressure for the MLs as an anthelmintic, creating a significant problem for the UK sheep industry. In 1994, P ovis developed resistance to SP plunge dips (probably through ineffective SP pour-on treatments) and, in 1995, resistance to the OP propetamphos was recorded. However, this mite population showed no side resistance to the OP diazinon.

Controlling sheep ectoparasites is a multifaceted operation, considering not just the efficacy of the ectoparasiticide itself, but also the effects on the sheep, human and environmental toxicity, economic losses to finished stock through MWPs and, specific to plunge dipping, costs of training and disposal.

In addition, some application methods could select for resistance in non-target parasites – in particular, GI roundworm resistance to MLs administered for scab control. Plunge dipping in diazinon remains – if used responsibly and correctly – the most effective method for controlling sheep ectoparasites (particularly scab), with no effect on GI roundworms – thus protecting the MLs as anthelmintics.

An integrated parasite control plan must be adopted, detailed in a flock health plan. Ideally, antiparasitic medicine use must be reduced then only used strategically. Permanent ectoparasites (scab and lice) enter flocks via introduction or contact with infested animals.

If a flock is not involved in common (communal) grazing, the risk of introducing these parasites can be reduced through good quarantining (with the assumption all incoming stock have scab) and adoption of an effective closed flock policy. In the UK, the Strategic Control of Parasites of Sheep promotes the isolation of all incoming sheep in a yard for 24 to 48 hours, and treatment for resistant GI roundworms and sheep scab, by administration of a moxidectin-based injection (giving 28 to 60 days’ protection against scab) plus a levamisole-based wormer.

Effective fencing/walling is also essential in:

Persistent infestations on common/communal grazings, shared by several flocks, are known for persistent scab and chewing lice – usually the result of a small number of recalcitrant flock-owners, sheep dealers or contact with feral sheep. Scab is generally slow to progress on open-fleeced breeds traditionally grazing common land and the continual persistence of scab results in a significant number of sheep with an acquired resistance, resulting in long sub-clinical disease periods.

On common or unfenced grazing, cooperation must be sought with neighbouring properties to attain equal standards of health. Where possible, flocks on the common should be gathered (when full fleeced) and plunge dipped simultaneously – not only providing the best protection against scab mites on untreated sheep and in the environment, but for peace of mind they are also protected against chewing lice, blowfly strike, ticks and keds, with no problems regarding anthelmintic resistance.