29 May 2017

Peter Edmondson offers practical guidance on how to tackle this challenge in cattle.

Figure 1. Medicine courses allow vets to discuss disease, simple diagnoses and treatments with farmers.

Everyone knows we have to reduce the amount of antibiotics in animals and humans, but, at times, we get so overwhelmed we move it to the bottom of our to-do list until tomorrow. Often, tomorrow never comes.

The majority of antibiotics are used in dairy cows. Approximately 40% are used in antibiotic dry cow therapy, 30% for treating clinical mastitis and the remaining 30% for other conditions and youngstock. It is clear mastitis accounts for the majority of antimicrobial therapy use in dairy cows. Use in beef animals is much lower.

So, how can we tackle this challenge?

It is essential every practice has an agreed policy on reducing antibiotic use. If vets or staff are sending out different messages, clients will become confused and wonder what sort of practice you are running.

Practices will benefit from having an agreed policy on reducing overall antibiotic use and the use of critically important antibiotics (CIAs). Remember, a team approach works best, as everyone achieves more together. So, some questions may include:

Practices will benefit from having standard treatments for common conditions. The author recalls, years ago, being asked by a farmer why he used a different antibiotic to a colleague for the same treatment and why his dose was different to some colleagues. This does not inspire confidence in farmers and can be a poor reflection on the practice.

Sometimes, we need to get our own house in order before we start criticising others.

It is tempting to start talking to farmers about antibiotics, but vets may be better off asking them their opinions. How do they feel about, for example, antibiotic use and resistance issues in humans and animals? Vets may be surprised by what farmers say – they may be more committed to reducing use than you.

It is always a good idea to not only hear farmers’ opinions and views, but also to ask them if they have any questions before starting to talk about the subject. The author recalls a vet friend talking to a client who had a dog with a broken leg. His friend was showing the x-ray to the client, telling him the black areas were air and the white areas bone. The client told him he was a professor of radiology and his x-ray was underexposed.

Vets may find a large proportion of their clients are already committed to making this change, so all they need to do is help with the process and practicalities.

Most farmers have no formal training in the use of antibiotics. They do what they have always done, and, maybe, have picked up tips from their father or a friend in the pub.

Farmer medicine courses are very revealing (Figure 1). Many are confused, and when vets ask them about how and when medicines are used, they get a range of opinions. Farmers often use different dose rates, frequency of administration and duration of treatment.

Medicine courses are valued by farmers and allow vets to explain about disease, simple diagnoses and treatments. Most importantly, they get farmers thinking before reaching for a bottle of antibiotic. Many presume any ill animal benefits from antimicrobial treatment, but, often, do not consider metabolic or parasitic conditions. Vets are called to see animals that have not responded to treatment, only to discover they may have a displaced abomasum, husk or other non-infectious condition.

The BCVA’s MilkSure training will go a long way to educating farmers and getting them to think carefully about whether it is appropriate to treat with antibiotics. This is good for farmers and vets, and a very welcome toolkit.

Cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones had not been discovered when the author started in practice, yet vets had little difficulty in treating sick animals. A reliance exists to use more potent antibiotics where basic treatments could be used.

Japan has a state-operated veterinary service called NOSAI, which sets out treatments for common conditions that must always be followed. Starting with antibiotic A, if no response occurs then you move to antibiotic B, and so on. NOSAI does not allow use of the most potent antibiotics as first line treatment.

Significant farmer pressure to have access to CIAs exists. Vets must educate farmers this is not responsible use and teach them to use more basic antibiotics initially. If problems with response to first line treatment exist, a telephone call or visit is advisable.

A range of vaccines are available. For example, calf pneumonia is not as common as it was 20 or 30 years ago due to environmental improvements and widespread use of vaccines. More farmers are interested in vaccination and looking to control or eradicate disease.

The use of diagnostics to find out exactly what diseases are present must be encouraged. This allows vets to put control measures in place to minimise disease and maximise animal welfare, which has productivity benefits for farmers. This allows vets to ensure they are using the most appropriate treatments for the conditions on each farm.

Many articles exist, and meetings held, about selective dry cow therapy and vets know this makes sense. Many farmers carry out this practice routinely – some have reduced antibiotic dry cow therapy use by more than 50%.

Fewer than 60% of cows receive an internal teat sealant at dry off. An internal teat sealant has been proven to reduce clinical mastitis by 25% to 30%. More research probably exists into the benefits of internal teat sealants than any other aspect of mastitis control. It makes sense for all herds to use an internal teat sealant.

So, farmers starting to use an internal teat sealant, with an average mastitis rate of 40 cases per 100 cows, will reduce the number of treatments by 25%. This reduces overall use for clinical mastitis from 30% to 22%. Combining this with selective dry cow therapy could reduce overall antibiotic use by more than 25%.

Malnutrition increases susceptibility to disease. If calves are kept in barns with poor ventilation, the risk of pneumonia will increase.

Every year, farmers need to complete a herd health plan. This can be completed in the surgery, but it may be better to take a more proactive approach and walk around the farm – look at the animals, their condition and housing – and discuss overall health and the ways things can be improved to the benefit of everyone.

Many farmers want more veterinary involvement and it is down to vets to inform farmers about services they can provide. Too often, vets assume farmers know what they do; however, many do not. Vets often assume farmers may not be interested in X, Y or Z, but will often be proven wrong.

Think of a herd visited every two weeks to carry out fertility work. The vet asks the farmer about, for example, the calves – how they are getting on, growth rates, disease and mortality. The vet is expressing interest. At the end of the visit, the vet suggests walking around the calves, asking questions, listening and offering help, as appropriate. This is an easy way to express interest and grow work.

Immune enhancers are now available for dairy cows. Most diseases and problems have been created by the way stock is managed, and solutions must be found. New antibiotics are unlikely in the future, so vets will be looking more at novel ways to enhance immunity to minimise disease.

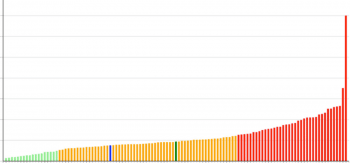

Virtually all practices have computerised programs that can give a detailed breakdown of antibiotic sales on a client-by-client basis. It can be useful to benchmark clients in overall and different categories of antibiotic use (Figure 2).

Benchmarking can be a very persuasive tool. For example, vets could invite 10 farmers to a lunch meeting and show their results, which would, of course, be anonymous. Ideally, one farmer will have a low level of overall antibiotic use and does not use CIAs. If it is a dairy farmer, choose one already using selective dry cow therapy and internal teat sealants. This person then becomes the advocate of the meeting. If he can do it, others will think about how they get to his position.

Everyone knows changes are coming and everyone wants to get there. Farmers do not really like listening to vets, but they do listen to other farmers.