1 Oct 2024

Bridget Girvan recounts the information and ideas shared at this inaugural gathering of vets and academics.

Figure 1. The inaugural udder cleft dermatitis steering group meeting.

On 26 June, 17 vets, technicians and academics attended the first UK udder cleft dermatitis steering group meeting, facilitated by NoBACZ Healthcare (Figure 1).

Udder cleft dermatitis (UCD) is a skin condition in dairy cattle causing mild to severe lesions which affect the anterior junction between the udder and the abdominal wall, or between the front quarters (Figure 2).

Known sequelae can be severe, including mastitis, embolic pneumonia and haemorrhage due to invasion of subcutaneous blood vessels, which can result in the death of the cow. Lesions take a long time to heal and reoccurrence is common1.

Despite the welfare implications of these lesions and the potential effects on productivity, relatively little is known about the disease pathogenesis, clinical course and optimal management. A few European studies have investigated disease prevalence and potential risk factors, but UK data has been lacking.

Lesions can be overlooked due to the anatomical location and the fact that affected cows seldom show generalised signs of disease. The aim of the meeting was to discuss UCD on a group level, collate current knowledge and ongoing work, and identify focus areas for further data collection or trial work.

The morning was spent reviewing current knowledge of the condition. Giovanni Capuzzello first presented a literature review. Within-herd prevalence studies undertaken in Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands show marked variation (0.3% to 38%)1-3.

Risk factors at cow level were identified as breed, indentation/fold at site of fore-udder attachment and increasing days in milk4. Environmentally, freestall housing and comfort rubber mats were shown to increase the risk of UCD5.

The difficulty of assessing the significance of risk factors was discussed – it can be hard to distinguish cause and effect as, for instance, certain breeds have differing fore-udder attachments or yield, and environmentally, high-yielding herds may be more likely to be bedded upon certain materials.

Analysis of bacterial flora from UCD lesions found Trueperella pyogenes and Bacteroides pyogenes most frequently present.

A Dutch study found no evidence of Treponema species on culture or histopathology6. A UK report did identify Treponema species, but they were not the species associated with digital dermatitis7.

A recent case of renal amyloidosis associated with UCD in a dairy cow in the UK was presented8. This prompted a discussion about UK diagnostics, tracking of UCD diagnoses at Veterinary Investigation Diagnosis Analysis level, and the difficulty in identifying acute inflammatory markers, as most cases are chronic by the time they are discovered.

Will Gratwick then presented initial findings from a UK study investigating prevalence and risk factors for UCD. In 2023, 28 herds with a median of 255 milking cows were enrolled, and a within-herd prevalence of 9.1% was found. Cows were scored for UCD, body condition score, cleanliness, hock lesions and udder conformation. Herd information was collected via questionnaire. Further modelling of data to assess the significance of findings from risk factor scoring will be presented at the BCVA Congress in October 2024.

During the study, the use of a “selfie stick” mirror and head torch was found to be suitable for lesion identification and scoring, and it was discussed how this could be introduced into a monitoring programme to assist with recording of disease progression and treatment outcomes.

Given the lack of obvious infectious cause, it has been hypothesised that perpetuation of the disease may be more likely due to an inhibition of healing or protraction of inflammation at cow level, potentially due to a genetic susceptibility9.

Mike Kerby presented similarities to a human disease of current medical interest: human chronic venous ulceration, which has a known genetic susceptibility. Various macroscopic and microscopic pathological changes lead to accumulation of iron at the site of vein damage, in turn maintaining macrophages as type 1 (pro-inflammatory) rather than type 2 (anti-inflammatory).

This type of cellular picture has been observed in the endometrium of cattle with endometritis, and Dr Kerby has postulated that a similar pathological process may occur in cattle with UCD. Assessment of skin biopsies from UCD lesions could, therefore, include macrophage typing, fibroblast typing and haemosiderin levels.

Milk recording data could also be analysed from affected cows to investigate possible trends within familial lines.

Figure 3. Case progression of an udder cleft dermatitis lesion during treatment:

Only limited research has been undertaken for UCD treatments. A 2018 Dutch study used daily treatment of severe UCD lesions with an alginogel for up to 12 weeks10.

Treated animals were 3.4 times more likely to improve versus untreated controls, but less than 10% of lesions healed completely. Improvement varied between herds, and five-plus parity cows were found to be less likely to improve. In 2021, a topical chelated copper and zinc spray was trialled in Sweden, but was not found to be effective in promoting healing1. Given the anatomical location of lesions, it is challenging to find a treatment that ensures sufficient contact time and adhesion to promote healing. Recent UK work presented by Mike Kerby, undertaken in conjunction with Patricia Simoes and Ian McCrone, investigated the use of NoBACZ Healthcare’s topical rapid-drying liquid barrier dressing containing a natural biopolymer with “spacer” metal ions11 as a treatment for UCD. Results were promising, and the paper is awaiting peer review and publication.

Twenty-six animals with active UCD lesions were visited by a vet weekly, had their wound cleaned and product applied. Wounds were assessed and scored for odour, discharge, depth and signs of healing (scab formation, granulation tissue bed and re-epithelialisation) at each visit for four to nine weeks.

77% of lesions were fully healed by week nine, with the other 23% showing signs of re-epithelialisation. This product is hydrophobic and immediately creates a waterproof barrier, then sets, which is beneficial for use on wounds in challenging farm environments. It also self degrades following application, so no removal is required, and is a food-grade product, so poses no issues with milk or meat that may subsequently enter the food chain.

Different treatment protocols were discussed, and it was concluded that a daily application is likely needed for three to five days following lesion identification, then weekly or bi-weekly reapplication until wound closure is observed.

Weekly reassessment fits well with routine fertility visits. It was agreed that simplicity and farmer practicality are paramount to provide an effective treatment protocol.

Discussion centred around which criteria could be used on farm to determine whether treatment of UCD was required, with the consensus being if any malodour, discharge or broken skin were identified then treatment should be initiated. Avoidance of over-vigorous cleaning was considered important to reduce haemorrhage, and scabs should be left in place where possible. More research is required to demonstrate whether analgesia is indicated as part of the treatment protocol (Figure 3).

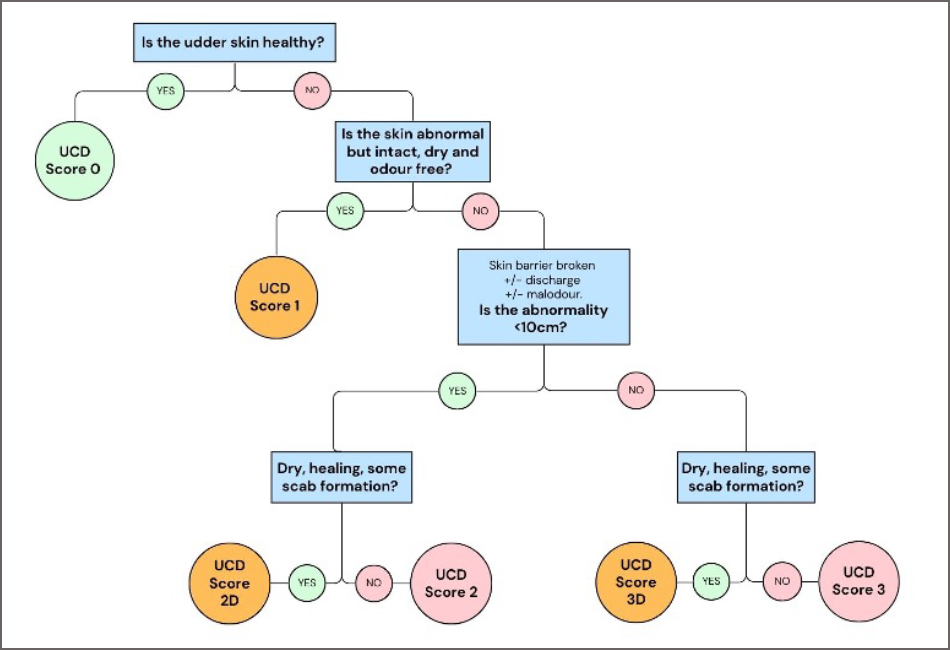

It was suggested that a need exists for regular recording of lesions. Various scoring systems exist in the literature1-3; however, group members’ experience of using these resulted in them producing a scoring system that they felt was more appropriate (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Proposed on-farm scoring system for udder cleft dermatitis.

Mixed wound pictures exist between farms and even within individual lesions, at times, so a clear case definition and scoring system would be beneficial to allow more consistent monitoring, reporting, and to include UCD in farm assurance schemes or milk contract requirements in the future.

It is evident that much more research into UCD is required, as it is hard to find a common theme from existing studies. However, several steps can be taken at farm level to increase awareness and data collection.

Early identification of UCD cases is important to promote cow welfare and increase the likelihood of recovery without adverse sequelae. Introducing UCD monitoring, and using farmer-friendly scoring systems, serves to inform farmers of the significance of UCD in their herds and effectiveness of any treatment protocols.

Diagnostic samples from UCD cases could inform future decision-making. This might include swabs from early cases to assess bacterial flora, or punch biopsies from mild and severe cases for histopathology.

Further sampling is required to distinguish whether mild (grade one) lesions reflect early or late stages of the disease; that is, are they developing or healing lesions, or possibly a mixture of both?

Where vets are aware of herds with UCD, a discussion with their laboratory clinicians on a suitable sampling protocol would be advised. Heifers and dry cows are groups for which we lack data due to practical barriers to lesion observation.

Udder conformation is a physical trait that can be targeted for breeding, so in herds with high prevalence, concentrating on genetic improvement of fore-udder attachment may contribute to a reduction in prevalence.

Further research into the effects of UCD on productivity, such as milk yield and fertility, would assist vets and farmers alike with treatment protocols, disease prioritisation and culling decisions.

Overall, it is evident UCD is a challenging condition to manage, and scope exists for a lot more research to inform an evidence-based approach to the condition. However, UK work is awaiting publication that will assist with understanding disease prevalence, potential risk factors for disease on farm, and treatment protocols.