6 May 2022

Owen Atkinson BVSc, DCHP, MRCVS looks at what farm vets can learn when trying to persuade farmers of the need to vaccinate their herds or flocks.

The COVID-19 pandemic has taught us many things. One is that people’s attitudes towards vaccination are complicated. Despite an unprecedented public health campaign, a news story dominating our headlines for two years and the fact that vaccines are free of charge, an estimated one in six eligible people in the UK has not had their COVID vaccine.

Why is this, and what can we learn when persuading farmers to vaccinate their herds or flocks? The reasons people are hesitant to, or do not, get vaccinated against COVID-19 have been summarised by the Office for National Statistics (2021) and include:

Although our focus may be on the rabid anti-vaxxers and conspiracy theorists, in fact the reasons why most people who don’t get vaccinated take that particular path are far more innocuous. In the same way, the reasons why farmers don’t vaccinate their animals are probably more frequently because they adopt a banal non-choice behaviour, as opposed to using a rational and active decision-making process.

For farmers not vaccinating, one might be tempted to add “cost” to the aforementioned list. However, in the author’s opinion, the practicalities and convenience factors of vaccination – for example, getting the correct injection interval or physically administering the vaccine – are more likely to be barriers than the cost, which for most vaccines is very modest. Indeed, a study by Richens et al (2015) indicates factors other than cost are usually more important for farmers who decide not to vaccinate.

This article explores some of those themes, and how vets can improve infectious disease control through greater uptake of routine vaccination.

In Britain, approximately 36 vaccines are licensed for use in cattle, and 86% of dairy farmers use one or more (Richens et al, 2015) in some form or other. Table 1 shows results from a survey by Velasova et al (2017), indicating the prevalence of use of vaccines to some of the common pathogens.

The highest prevalence of use is bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) vaccination, closely followed by leptospirosis and infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, where approximately 50% of dairy farmers were using these vaccines to some extent. However, the correct use is likely to be considerably less (Cresswell et al, 2014; Meadows, 2010).

Commonly, errors in vaccination can occur due to incorrect route of administration, incorrect dosage, failure to complete a primary course, incorrect booster intervals and failure to store the vaccine properly (for example, cold chain insecurity).

Certainly, infectious disease control is not all down to vaccination. In many instances, vaccination is simply not an option (for example, neosporosis, bTB). Even where vaccines are available, they rarely provide the sole answer to disease control; for example, BVD control, where identifying and eradicating persistently infected (PI) animals is also important. Nevertheless, a greater uptake of routine vaccination in livestock production is an important component in herd health, reducing reliance on antimicrobials and the consequent risk of antimicrobial resistance (O’Neill, 2016).

Infectious disease control should be seen within the wider context of overall herd health. For many farms, attention to other herd health areas – such as cow comfort, nutrition, building design and foot health – should arguably take priority over infectious disease control, as these are the more significant factors.

Ideally, though, attention is given to both areas: infectious disease control, which often includes vaccination and management of endemic “production disorders” such as lameness and ketosis.

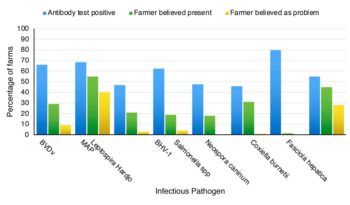

A survey estimating disease prevalences in 225 dairy herds throughout Great Britain, based on bulk milk tank antibody tests, shows uncontrolled infectious diseases are very common (Velasova et al, 2017). Figure 1 shows the prevalence of herds positive for some of the main infectious pathogens. Only herds that were not vaccinating for the particular pathogen are included in these results due to an inability to normally differentiate antibodies from natural exposure or vaccination.

The high prevalence of antibody-positive herds suggests active disease transmission is occurring among dairy cattle populations, and the available control measures are either not being implemented or not being effective. For example, the survey points to around two-thirds of herds being endemically infected with BVD virus, Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (Johne’s disease) and bovine herpesvirus-1 (associated with infectious bovine rhinotracheitis). Around half of all herds are infected with Salmonella, leptospirosis and Neospora.

It is interesting to compare this with farmers’ beliefs of whether their herds are infected, or beliefs of whether the pathogens are causing a problem in their herds. A marked lower awareness (or belief) exists of infection than the true prevalences. An even lower percentage of farmers actually believes these infections are causing problems in their herds.

In consideration of the disparity between disease prevalence and farmers’ beliefs in the risk, a common, but ill-conceived, concept exists among cattle farmers that exposing cattle to disease can be used as a reliable protective measure (Brennan et al, 2016; Frössling and Nöremark, 2016).

This notion is apparently seen more frequently among cattle farmers than other farm types. This can be a frustrating viewpoint to encounter in practice, for example, where farmers misinterpret bulk-tank positive results as showing healthy immunity to disease rather than evidence of uncontrolled circulating infection. Frustrating it might be, but it is understandable when farmers are used to the concept of top-up natural exposure and immunity for endoparasite control, or the old (pre-commercial vaccine) notion of maintaining a BVD PI animal to expose and immunise bulling heifers to the virus prior to service.

It can be a daunting task, faced with this belief, to try to explain and reason with farmers to teach immunity and epidemiology concepts that are, even to the most scientifically minded, pretty complicated.

We all encounter in our lives decisions that must be based on our perception of risk, and our trust in information available to us. As none of us are all-knowing, it is usual to seek trusted advice to assess risks in areas outside our expertise. For example, before deciding to travel to a far-flung destination, we would probably go to the Foreign Office’s website, where a country’s rating of green, amber or red quite clearly indicates risk to travellers. Most of us would probably avoid “red” countries (often zones of active conflict), demonstrating an implicit trust of the pre-assessed risk.

Farmers have complex and nuanced decisions to make when it comes to infectious disease control. The effects of endemic infection within a herd are not usually particularly obvious or easy to quantify. Therefore, vets are often the trusted expertise that farmers rely on in their decision-making. Indeed, a survey of 25 British dairy farmers by Richens et al (2015) found that farmers, on the whole, do trust their vets’ advice regarding vaccination, but for other reasons may not choose to follow their advice.

So, if a farmer trusts the vet’s advice, why not follow it? The answers may be surprisingly similar to the list of reasons why people do not get their COVID-19 jab. Never underestimate the convenience factor.

Infectious diseases are rife with ambiguity. Uncertainty breeds indecision and poor risk analysis. For example, many uncertainties surround testing, which as veterinary scientists we accept and have skills to assess.

We tend to understand the balance between test sensitivity and specificity, and appreciate no test is perfect: we have tools to interpret the shades of grey and are not dependent on black or white answers. Most farmers, however, will not feel as comfortable with these grey areas, and we should be careful about assuming their understanding of results. It is important to take time with our clients, and establish their perspectives and perceptions.

A lack of “proof” is a problem when considering the effect of an infection. We not only ask our farmers to trust our interpretations of test results, but we ask them to trust us that these diseases are causing their herds economic harm.

Sadly, many of us are aware how it can take a catastrophic abortion storm, obvious clinical disease or animal deaths attributed to a particular pathogen to persuade a farmer to vaccinate and take other disease control actions. If only they had trusted – or, more to the point, acted on – our advice beforehand. Too often it requires tangible catastrophic consequences for a farmer to perceive a disease is worth taking action over, and even then, a short time later the perception can shift back to allow benign neglect to re-establish itself.

Perception is reality, as the phrase goes. If a farmer does not perceive a problem, it can take effort for a vet to change that (Figure 2). A survey of 15 farm vets by Richens et al (2016) suggested that vets are often torn between wanting to do the best for their clients, yet not having the time, energy or resources to persuade a farmer to undertake infectious disease control, unless the farmer is already demonstrating a proactive nature and driving the process themselves.

National disease control campaigns may help in this regard, as they can go some way in educating farmers about particular diseases and enable them to form more accurate perceptions themselves.

In the dairy sector, some of the retailer-aligned farm assurance schemes require a proactive approach to infectious disease monitoring and control. At the least, this means targeted surveillance and a periodic risk review for each pathogen. In the author’s experience, for some farms this has been the impetus required for them to make significant progress, for the benefit of their animals, their overall herd health and the sustainability of their business.

While it is not always easy for individual vet practices to drive such a coordinated approach for their clients, it creates a model that can be followed. A long way to go remains in ensuring that vaccination is accepted, implemented widely and done correctly by the majority of farms. This presents an opportunity for vet practices to not only sell vaccines, but vaccination as a service.

This could encompass implementing a vet-led disease control plan that may include vaccination protocols using “vet tech” support to administer the vaccines correctly to the correct animals at the correct time. For many time-pressed farmers, this could be a solution that achieves a better level of compliance and effectiveness than is otherwise likely.

Infectious diseases are common in British herds, yet control is often uncoordinated and ineffective. Excellent communication skills and commitment are required by vets to help farmers review their goals and manage infectious disease better. Vets need support here, and to some extent this is provided by pharmaceutical companies.

Uptake of routine vaccination, where available, should be the industry norm and form part of targeted control strategies. It might be possible to provide imaginative solutions to vaccination by thinking beyond selling vaccines and towards providing vaccination services through which better compliance and effectiveness can be achieved. New testing possibilities should be embraced to enhance infectious disease surveillance and underpin our control efforts and value to farm clients.

On a positive reflection, the COVID-19 experiences have given us a lot of things. For many of us, we find ourselves now speaking with a more scientifically literate farming community. Like us all, farmers are perfectly au fait with lateral flow tests, PCRs, false positives/negatives, and, of course, the importance of vaccine boosters. It might actually mean we’ve had no better time to get our important infectious disease messages across.