22 Apr 2025

Lisa Morrow DipAppChemBiol, BMLSc, DVM, MSc(VetEpi), DLSHTM, PGCHE, FHEA, MRCVS, Victoria Henry BVetMed, MRCVS, Isobel McCarroll, MVB, MRCVS, Mandy Hill, BSc(Hons), PgD, MBA, Kerry Williams, BAVetMB, PGCHE, FHEA, MRCVS, share the topics of discussion from the latest Shelter and Charity Veterinary Association Conference.

Image: Halfpoint / iStock

It is recognised that the re-homing of animals in the UK is carried out by a diverse network that includes national charities, local charities, non-registered groups acting as charities, businesses and individuals.

Re-homing activities can be led by charity-employed staff or volunteers, or a combination, and animals can be housed in a range of environments. One thing that is consistent is the majority of these animals will receive veterinary care before they are re-homed, and much of this activity happens in general practice.

The 2023 Cats Protection Veterinary Capacity survey found that 80% of those surveyed working in non-charity specific practice are involved in some form of charity work for a broad variety of different charities1. Veterinary professionals in practice do play a significant role in re-homing animals and have an influence on the health and welfare of these animals.

The Shelter and Charity Veterinary Association (SCVA), formerly Association of Charity Vets, held its 13th annual conference at Harper and Keele Veterinary School on February 1-2. The conference brought together 110 veterinary surgeons and veterinary nurses from the UK, and the wider European community, who are employed by animal charities, work in private practice or who teach in veterinary schools. The conversations we have are relevant to all practising veterinary professionals.

The second day of the conference was devoted to discussing the challenges of re-homing animals. Keynote speaker Mandy Hill, the cat re-homing coordinator at RSPCA Crewe, Nantwich and district branch, and formerly head of operations (north) for Cats Protection, started the day off with a presentation that outlined the challenges re-homers face with particular regard to the veterinary-related aspects of re-homing. The delegates then split into groups to identify areas of challenge and propose solutions that veterinary professionals can influence.

Key topic areas discussed included quality of life, approach to case management (medical and behavioural), the burden of pet ownership, re-homers’ limitations on capacity for care, and minimising obstacles to re-homing.

Our aim in writing this commentary is to disseminate approaches veterinary professionals can take to optimise their input into the re-homing process. Ultimately, this will support an efficient, patient-centred experience for animals who need new homes.

So, how can vet professionals help with re-homing? What role can we play to facilitate displaced animals getting to a new home? What follows is some highlights of our discussions.

Recognising the context of the animal is key to vets assisting in re-homing. These animals are not in a stable, domestic environment and their current environment is highly stressful.

Long periods of time in care are not good for the animals’ mental health. The goal is to move them out of this situation as quickly as possible and for the re-homing event to be a success for both the animal and the new owner.

Veterinary professionals can influence length of stay in many ways; for example, there are often multiple treatment options available for a given condition. Choosing one that has the fastest recovery/stabilisation time is going to help with finding a home sooner, which decreases length of stay and, therefore, improves the welfare of the animal.

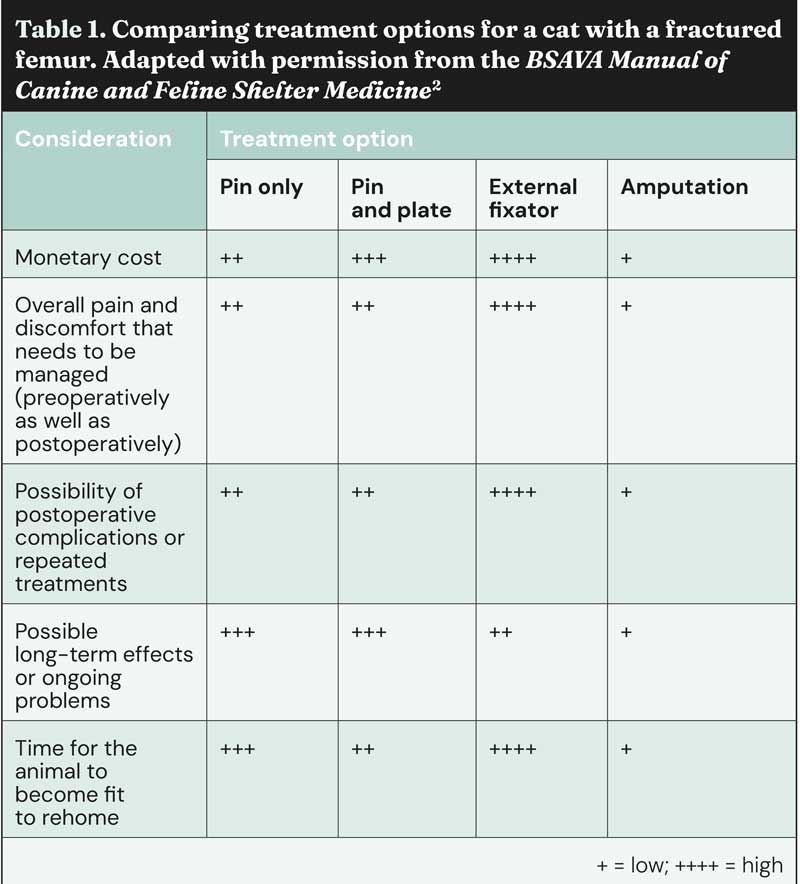

Similarly, choosing a treatment with the lowest morbidity and lowest risk of short-term and long-term complications will improve welfare. Consider amputation versus surgical fixation options such as pinning, plating or external fixator in the repair of a fractured femur.

With amputation, recovery is faster; the animal is ready for homing quicker; there is no need for cage rest and associated implications for welfare (stress); easier postoperative management for re-homers; lower risk of complications and need for revision surgery; lower cost; and three-legged animals are easier to re-home (Table 1).

Performing multiple preventive medicine treatments at the same time will greatly decrease the time it takes to get an animal ready for re-homing.

This also improves welfare for both the animal and the re-homer, in that it reduces number of visits to the practice.

Neutering cats at a young age will reduce length of stay and facilitates neutering before homing, which supports population management.

We often think cost drives many decisions in rescue animals; while it is always a consideration, often, if weighing up treatment cost versus time in care, reducing time in care takes priority.

It is worth remembering that in addition to the obvious welfare implications, increased time in care itself leads to increased cost of re-homing.

Vets can help reduce the burden of pet ownership by offering treatment choices that reduce or eliminate the need for ongoing treatment (yet not at the cost of keeping an animal in care for extended periods of time). This can be tricky to manage and will depend on the condition in question.

Also, “treatment-free” is not always an option.

A critical role the vet plays in re-homing is in the initial assessment of the animal’s condition. It is really important that both short-term and long-term prognosis (and prospect of re-homing) is considered.

The animals’ current and future quality of life should be at the forefront of our minds, and we should not be shy about offering euthanasia as an option for those animals where prognosis and quality of life is poor.

Non-veterinary trained people working to re-home animals do not want animals to suffer, yet often lack the knowledge of what this means from the animals’ perspective and don’t know when there is very little chance of improving quality of life.

Veterinary professionals are well placed to help them with this assessment, and it can be a positive dialogue with our clients.

Linked to the initial assessment is the idea of understanding the limitations of our clients or, in other words, thinking about their context.

For clients who are re-homing animals, if we consider their level of knowledge and adjust our dialogue to optimise understanding, this will help them in their decision making (often done by committee or in consultation with others in their organisation) and in their re-homing efforts when speaking to potential adopters.

What concerns do they have about costs? Some treatments may not be easily managed by the carers; what works for them? What facilities do they have for their animals? If we are dealing with infectious disease, do they have isolation facilities? What is the level of understanding of biosecurity?

Sometimes, we need to manage cases where there is a strong emotional attachment. Having a good understanding of these human factors can really help assist re-homing.

Taking a pragmatic approach to work-up of cases is key when working with animals awaiting adoption; for example, if a large elderly dog has stiff hips on manipulation, often physical examination is sufficient to support a diagnosis and treatment plan.

Imaging can confirm the diagnosis, but this adds cost, time and anaesthetic risk, usually without altering the treatment plan.

Additionally, incidental findings can lead to complex histories that impact the re-homer’s ability to find a home, as many potential adopters are concerned about health and insurance options.

In complex cases, it is very helpful for vets to be involved in discussions with potential adopters to help relieve fears about prognosis or ongoing care needs.

In essence, they become a part of the re-homing team.

Developing this relationship with the adopter often leads to vets providing ongoing case management after adoption. This continuity of care is a real welfare benefit for the animal.

Behaviour issues are common, and treatment often takes a long time. A time-effective approach to managing these cases may involve working with both the re-homer and a potential new owner early in the process.

Once the animal shows good progress, it can be re-homed and its rehabilitation continued in its more permanent environment. The task of finding that new owner falls to the re-homer, but if we as veterinary professionals are open to the idea of working in that multi-client environment, the animal’s welfare is best served.

Many veterinary professionals volunteer as fosterers themselves and are well placed to help with re-homing in this way.

Practices can support re-homing by being ambassadors of the local re-homing network that they work with. This can be publicising their work, getting involved with fund-raising, help with recruiting fosterers and recommending clients to adopt from them.

Vets are key educators for people doing re-homing and can be very influential; for example, framing what constitutes good welfare, pointing out issues with overcrowding and mixing, discussing disease control in a multi-animal environment and minimising stress, general management and husbandry for different species.

Re-homers consistently have more animals needing their support than they have capacity for, and animals with complex and/or chronic health conditions take longer to re-home.

If vets avoid suggesting relinquishment to shelters as an alternative to euthanasia for owned animals with significant health concerns, this will reduce the burden on re-homing organisations and prioritise the welfare of these animals which are likely to spend extended periods, and possibly their final days, in a shelter environment.

In a similarly preventive approach, vets as educators will always have a role in promoting responsible pet ownership to our clients and the public.

Doing this can also prevent relinquishment of animals into care.

It is hoped that this commentary will promote further conversation within the profession and between veterinary professionals and their re-homing clients. For many of you reading this, a lot of what has been said won’t be new and will be part of your working relationship with local re-homing groups.

Hopefully, this has reinforced the vital role veterinary professionals play in the re-homing of animals, and how much more there is that we can all be doing. The key to this process will always be clear and open dialogue between the shelter and veterinary sectors.

The SCVA is keen to support this work. If this article has piqued your interest, consider joining us. Our website (www.scvassociation.org.uk) provides relevant resources and we offer webinars on related topics, not forgetting our thought-provoking annual conference.