13 Mar 2017

Chris Shales looks at the presentation, prognosis and treatment options surrounding this category of wound in dogs.

Oropharyngeal stick injuries (OSIs) are usually the result of a dog running on to a stick that is fixed at one end, typically during play. The injuries are reported more commonly in medium or large breed dogs, but are not exclusive to this demographic.

OSIs are usually categorised as either acute (fewer than seven days old) or chronic, and this is reflected by the differences in both presentation and prognosis associated with the two groups. Chronic OSIs typically present with abscess formation secondary to the presence of foreign material and can represent a challenge to the clinician in terms of identification, localisation and successful retrieval of the material from within the tissues of the head, neck, axillae and so on.

Improvements in our understanding of OSIs and a desire to avoid the worse prognosis associated with either chronic presentation or acute cases with undiagnosed oesophageal damage have led to a tendency towards more aggressive investigation and management of acute cases over the past 15 years.

This trend has been reflected in the literature as early discussion focused mainly on the chronic injury (White and Lane 1988; Griffiths et al, 2000; Nicholson et al, 2008), whereas more recent reports have included a predominance of acute cases (Doran et al, 2008; Robinson et al, 2014).

In line with this evolution, this article will focus on the diagnosis, investigation and treatment of acute OSIs in the dog.

The classical presentation often includes an eyewitness account of the accident and clinical signs that can include pain, ptyalism, bleeding from the mouth, SC emphysema, swelling and lameness. Tetraparesis, secondary to wood foreign body within the vertebral canal, has also been reported (Rayward, 2002).

More subtle presenting signs can occur in those cases not presented immediately or in cases thought likely to have suffered an OSI secondary to chewing rather than playing with sticks (Griffiths et al, 2000).

In these dogs, signs can include inappetence, pyrexia, dyspnoea, lethargy and halitosis, in addition to those already mentioned.

Conventional radiography can be useful to confirm a penetrating injury by identifying the presence of free gas that can occur within the cervical fascial planes, axillae and mediastinum (Figures 1 and 2). Positive findings do not give an indication of the severity of injury or likelihood of significant foreign body debris.

The author has seen free gas within the cervical planes and a low volume pneumomediastinum associated with a shallow (5mm) penetration of the oropharynx in a dog. Additionally, a possibility exists of false-negative results in cases with confirmed OSI without evidence of free gas on conventional radiographs (Doran et al, 2008; Robinson et

al, 2014).

CT can be useful (Figure 3) – particularly when considering orbital or ophthalmic injury associated with OSI – and, while it should be less prone to false results than conventional radiography, these can still occur.

Ultrasound and MRI have been used to investigate both acute and chronic OSIs, but are not usually recommended as a first line investigation modality.

Thorough evaluation of the mouth, pharynx and oesophagus represent the author’s technique of choice when evaluating acute OSI cases. With the dog anaesthetised and a mouth gag in place, two bright laryngoscopes with relatively long blades can achieve excellent evaluation of the rostral injury sites (for example, sublingual, pharyngeal arches, soft palate, tonsillar crypts and oropharynx).

It is important to bear in mind the likely trajectory of the stick and the fact structures such as the soft palate offer little resistance to its onward passage, making multiple injuries relatively common.

Evaluation of the upper oesophageal sphincter in the region immediately dorsal to the larynx provides a significant challenge due to the tendency towards red out when using flexible endoscopy. The author finds a sigmoidoscope invaluable for evaluating this region (Figures 4 and 5).

Evaluation of the oesophagus caudal to the larynx is usually best achieved using either a flexible endoscope or sigmoidoscope. Insufflation of the oesophagus should be avoided in cases where full thickness oesophageal wall perforation is possible due to the risk of tension pneumothorax.

It is essential to identify the location of all injuries associated with acute OSI to make the correct treatment decisions.

The negative prognosis associated with oesophageal injury makes evaluation of this area an extremely important aspect of the initial assessment.

Open surgical exploration of the neck has represented the technique of choice in cases with confirmed penetrating injury to the oropharynx. This approach resulted in far fewer cases progressing to become chronic in recent years and has improved the outlook for those animals suffering from oesophageal perforation. Open exploration aims to achieve lavage of the tract created by the stick (Figure 6), and facilitate recovery of foreign material and suture tears to the oesophagus.

Surgery is performed via the ventral midline, but access can be difficult – particularly in the region of the cranial oesophagus immediately dorsal to the larynx.

In terms of deciding when to operate, the presence of free gas within the cervical tissues on conventional radiography has been used to indicate the need for open cervical exploration and, as one would expect, this was proven to be associated with a low risk of progression to chronic presentation (Doran et al, 2008). Interestingly, two-thirds of the cases operated in the Doran study using this protocol were actually found not to have significant foreign material. It is possible these animals did still benefit from lavage of their injuries.

One case (1 out of 41) in this series that was not taken to surgery developed an abscess secondary to retained foreign material following a false-negative finding (no free gas) on conventional radiography.

Overall, open surgery remains indicated whenever confirmed full thickness perforation of the oesophagus is present and can be justified in most cases where confirmed stick penetration into the cervical tissues exists, to minimise the risk of progression towards chronic presentation due to retained foreign material.

The use of rigid endoscopy (2.7mm 30° forward oblique 18cm long) has been reported for the successful evaluation and treatment of acute OSIs without oesophageal injury and where the scope could reach the full depth of the stick tract (Robinson et al, 2014). This technique replaced the need for CT or radiography in most cases and also avoided the need for open surgical exploration.

The scope was introduced via the injury and the tract irrigated through the scope sheath via a low-pressure, gravity-fed system. Foreign material of approximately 1mm or larger was retrieved using forceps passed through the biopsy channel of the scope sheath (Figures 7 to 9).

Those animals with injuries that extend into the axilla or through the thoracic inlet can represent a significant challenge. Evaluation, lavage and retrieval of foreign material can be performed via open surgery or the use

of endoscopy.

Scope placement can be via the oropharyngeal injury or via the cervical incision and can be used to avoid the need for sternotomy in cases where the injury has extended into the thoracic cavity.

A conservative approach can be considered for those cases considered unlikely to have either retained foreign material or oesophageal injury, although this raises concern regarding how this conclusion is reached.

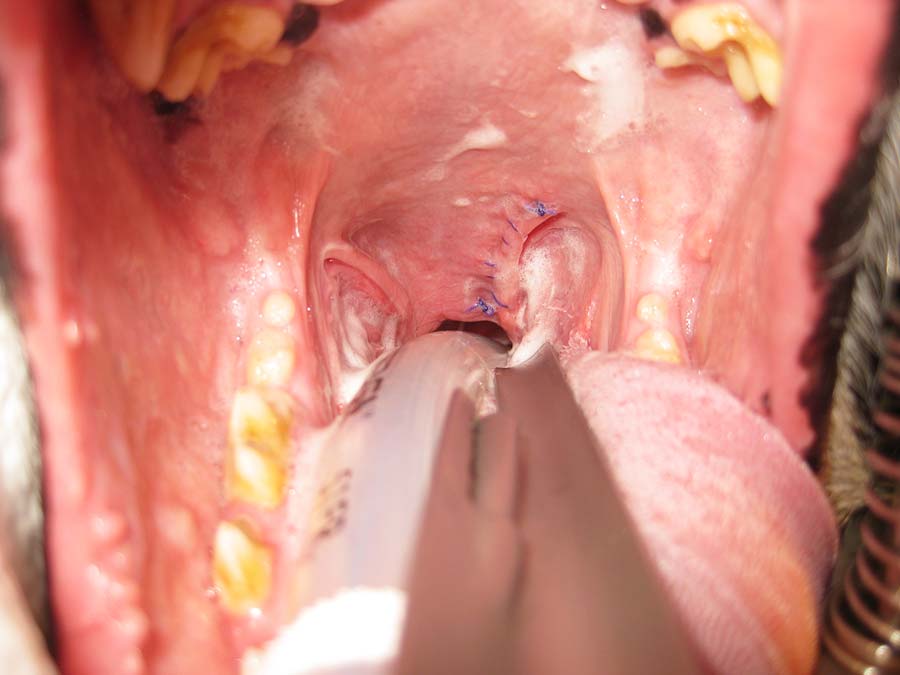

In terms of the oropharyngeal injury itself, reports differ as to whether the injuries are closed or left to heal by secondary intention. The author evaluates each case on its merits, but tends to perform primary closure of soft palate injuries (Figure 10) and leave the remainder open.

Oropharyngeal bypass is often not required, but can be important in cases where there has been damage to the oesophagus or the entrance to the upper oesophageal sphincter. Gastrostomy tube placement under endoscopic guidance is usually recommended and can be used to provide all water, food and medication requirements until such time as the injury is considered sufficiently healed.

The majority of dogs in which all injuries are identified and treated appropriately as acute cases make a full recovery (White and Lane, 1988; Griffiths et al, 2000; Doran et al, 2008; Robinson et al, 2014).

However, oesophageal injury can be problematic and, despite significant management advances, remains associated with a worse overall prognosis (White and Lane 1988; Doran et al, 2008).