18 Dec 2017

William McFadzean discusses up-to-date guidelines, techniques, equipment and new drugs that may be licensed in the future. Article also includes video content.

Provision of anaesthesia and appropriate analgesia are part of the daily routine of veterinary clinical practice.

While many think of this topic in terms of the drugs that can be given, it also encompasses the use of specific equipment and techniques to provide best patient care in the perioperative period. This article will discuss new drugs on the market and ones that may be licensed in the near future, alongside up-to-date guidelines, techniques and equipment.

Comprehensive guidelines on the recognition, assessment and treatment of pain are available for use in small animal practice1,2. These documents are easy to use and cover all aspects of analgesia.

The licensing of opioids and the increased emphasis placed on the recognition and treatment of pain in animals has led to an increase in the number of vets prescribing perioperative analgesia3. The development and validation of species-specific pain scales has done a lot to advance the recognition of pain.

The short-form canine and feline Glasgow Composite Measure Pain Scales are easy to implement in the clinical setting for postoperative and acute pain. Scales are also available for use with patients suffering from chronic, arthritic and oncological pain. The Liverpool OA in dogs (LOAD) clinical metrology instrument (CMI), is specifically designed for dogs with OA. This CMI lacks an intervention score, but is a useful tool in tracking changes over time, and scores have been found to correlate with results of force plate analysis results in dogs suffering from OA.

Giving crystalloid fluids at 10ml/kg/hr during general anaesthesia is a paradigm that has, for a long time, formed the basis of the “surgical fluid rate”, with the aim of reducing potential complications from vasodilation and hypotension. This has been challenged due to the potential for worse outcomes when these higher rates are used4,5. Recommendations for the anaesthetised patient from the American Animal Hospital Association (AAHA) are for dogs to receive an initial rate of 5ml/kg/hr and for cats 3ml/kg/hr6. This rate should be reduced by 25% every hour of anaesthesia until the patient is receiving 2ml/kg/hr.

Blood pressure should be monitored and if hypotension is encountered, and suspected to be due to relative hypovolaemia, fluid boluses may be used. Initial crystalloid boluses of 3ml/kg to 10ml/kg should be given and repeated once, if needed. If the response to a crystalloid bolus is inadequate then a colloid bolus of 5ml/kg to 10ml/kg for dogs and 1ml/kg to 5ml/kg for cats can be given. These boluses should be given over 5 to 10 minutes as a set volume and not achieved by increasing the hourly fluid rate.

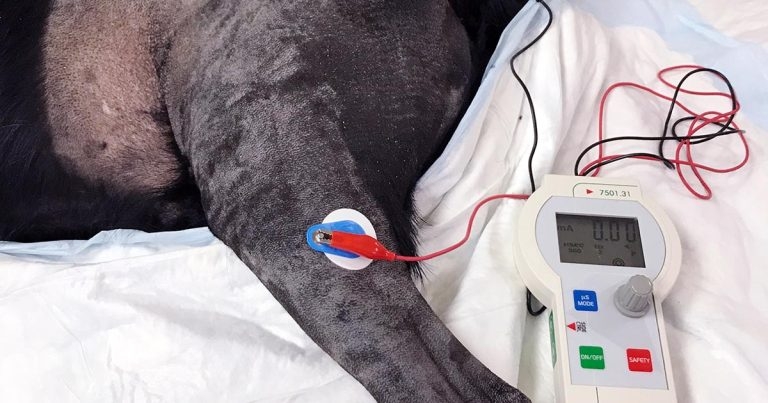

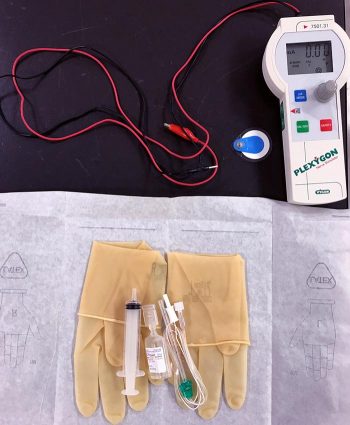

A major advance in procedural techniques has occurred in respect to regional nerve blocks. Movement away from a “blind” landmark-guided approach to use of peripheral nerve stimulators (Figures 1 and 2) and ultrasound-guided techniques should allow for more accurate placement and, therefore, effective nerve block. Deposition of local anaesthetic close to the nerve to be blocked also allows for a reduction in the total dose of drug used and, hopefully, reduced likelihood of toxic side effects.

Many useful texts are available that cover the topic in-depth7 or act as a handy patient-side guide8. Advances in local anaesthetic techniques are, in part, driven by the desire to reduce opioid use in humans. The concept of opioid-free anaesthesia (OFA) in human medicine relies on the ability to stop the transmission of pain predominantly via the use of locoregional techniques. The translation of OFA into our veterinary medicine is, at present, hard to justify for routine clinical patients, but further advances in these techniques will aid its development for those cases that may benefit from reduced opioid use.

The reduction in cost of multiparameter monitors means they are accessible at all levels of veterinary practice. Their increased use will aid in increasing the knowledge base in practice and for the expansion in monitoring of additional parameters, such as oscillometric blood pressure. Alongside the reduction in cost of standard monitors, an expansion of more advanced monitoring has also been seen.

High-definition oscillometric (HDO) blood pressure is the first non-invasive blood pressure device to meet the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine validation guidelines in conscious cats9. However, results from studies of anaesthetised patients failed to meet the criteria in both dogs and cats10,11. Despite not meeting validation criteria, accuracy and precision is improved in comparison to other methods. Additional information is available from these monitors, and pulse wave analysis can be used to derive information on stroke volume, stroke volume variation and systemic vascular resistance. The Memo HDO is available for veterinary patients and comes with computer software for in-depth analysis and evaluation of the information obtained.

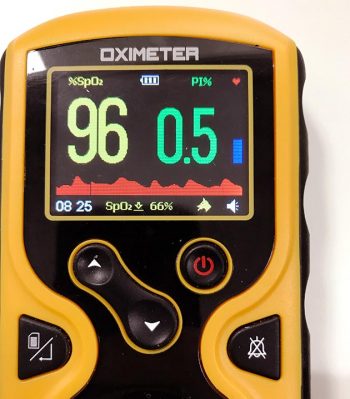

Pulse oximetry is a familiar technique for monitoring oxygen saturation. Updated versions of this technology use a rainbow spectrum of light rather than the traditional two spectrums of red and infrared. This change allows for measurement of other species of haemoglobin rather than those saturated with oxygen or not, allowing for more accurate monitoring of oxygenation. Most of these newer monitors also come equipped with analysis of perfusion index (PI), the variability of the pulse (Figure 3).

PI is a non-invasive measure of the peripheral perfusion calculated as the ratio of pulsatile flow to nonpulsatile blood flow at the site of reading. This can be used to find the ideal site for placement of the sensor, monitoring for changes in peripheral perfusion. The onset of general anaesthesia and successful locoregional anaesthesia are associated with an increase in the PI; therefore, changes in the PI can be used to monitor the success of a nerve block and to confirm a patient is appropriately anaesthetised12,13.

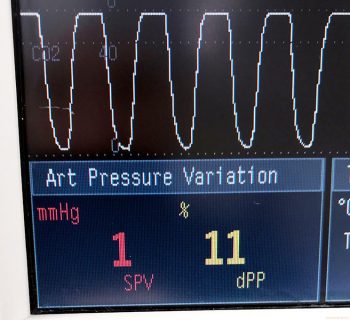

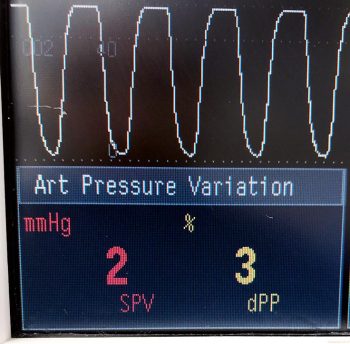

Pulse pressure variation (PPV) is derived from invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring, and is the difference between the maximum and minimum pulse pressure divided by the mean of these values over one respiratory cycle. A PPV of more than 13% has been shown to predict fluid responsiveness in humans14 and this idea has been taken forward in veterinary patients. PPV can be used as an early marker of haemorrhagic shock, with a PPV of more than 13% equating to about 20% blood loss15,16.

Plethysmograph variability index (PVI) is based on the same theory, but is a non-invasive reading taken from the plethysmographic waveform of the pulse CO-oximeter. Using the same value of more than 13% has been found to predict fluid responsiveness in 82.9% of cases17 (Figure 4). The Masimo Radical-7 is the most commonly used of these monitors in the veterinary sector and veterinary-specific sensors can be bought alongside the range of human sensors.

Although not new to the market, the veterinary formulation of alfaxalone has been licensed for the induction of general anaesthesia in rabbits. This makes it the first sole agent for the induction of anaesthesia in rabbits, in addition to holding a licence for the maintenance of anaesthesia by infusion in dogs and cats. Induction doses of 4mg/kg to 5mg/kg for rabbits are given on the data sheet, but, as in other species, lower doses may be required and the drug should be given until the desired effect is achieved. Familiarity with propofol still makes it the most popular induction agent; however, the additional licensing means under the cascade it should be used in these instances.

The alpha-2 agonist dexmedetomidine will be familiar to many for sedation and premedication, but it comes in a licensed 0.1mg/ml oral transmucosal gel for the alleviation of acute anxiety and fear associated with noise in dogs. One product had an excellent/good treatment effect in 72% of dogs that received it for firework noise anxiety18. An obvious side effect is the risk of sedation in dogs that receive it and, therefore, care must be taken to inform owners about accurate dosing and assessment of sedation. The gel should be given in the buccal pouch and may be ineffective if swallowed. It must also be remembered dogs that receive an alpha-2 agonist can appear sedated, but can respond suddenly to touch.

The product is not designed for sedation of animals either in or outside of the veterinary practice and should not be used for this purpose. Reports of its use for sedation in aggressive dogs do not seem sensible; the difficulty of accurately giving the gel within the buccal pouch of such a dog places veterinary staff in a dangerous position when other methods and sedation routes are available.

A transdermal solution containing 50mg/ml fentanyl was designed to provide long-lasting postoperative analgesia in dogs. Sadly, safety concerns of vets using the product and the requirement to hospitalise some dogs for up to two days after application have probably contributed to it being unavailable. The idea of sustained release (SR) formulations of commonly used perioperative analgesics has many advantages for animal welfare and clinical practice. Single injections of these drugs can result in multiple days of analgesia, reducing hospitalisation time and removing the need for owner compliance to give postoperative medication.

A 1.8mg/ml buprenorphine is available in the US for the treatment of postoperative pain in cats. A dose of 0.24mg/kg is given by SC injection one hour before surgery and repeated once daily for up to three days. It has been specifically designed to overcome the erratic absorption of the current formulations of buprenorphine following SC injection, which can result in plasma levels less than those required for analgesia19,20. Safety experiments using up to five times the recommended dose for nine days found the drug to be well tolerated, with adverse events, such as hyperactivity, difficulty in handling, disorientation, agitation and dilated pupils, reported in two cats21. Hopefully, the product will be released in the UK.

Local anaesthetics during orthopaedic surgery are an effective way to provide perioperative analgesia and a new preparation can last up to three days. It is a long-acting bupivacaine liposome suspension consisting of aqueous bupivacaine encapsulated in a honeycomb lipid bilayer. This lipid membrane undergoes erosion and reorganisation to slowly release bupivacaine. The product is approved for use in cranial cruciate surgery. Infiltration of the drug into the tissue layers at the end of surgery results in analgesia lasting 72 hours22.

Long-term and above clinical dosing can result in a granulomatous inflammation, but this is considered a normal response to the liposomes and not to adversely affect wound healing23. Preclinical human studies were undertaken on veterinary species and, therefore, safety data exist for uses other than the approved application. This product shows promise for expanded use in clinical practice.

Sustained release 72-hour duration meloxicam and buprenorphine are available from compounding pharmacies. While primarily aimed at the research market, this may provide insight into future advances. A single SC injection of SR-buprenorphine has been compared to repeat SC buprenorphine injections following ovariohysterectomy (OVH) in dogs24, and to repeated oral transmucosal dosing following OVH in cats25. Both studies found comparable postoperative pain scores between the SR and traditional formulations. Less evidence exists regarding SR-meloxicam, but, hopefully, this will become available.

Aside from new preparations for familiar drugs, development of novel therapies for treatment of OA is also fast evolving. A novel drug with the active ingredient grapiprant has been developed as an EP4 prostaglandin receptor antagonist. This non-COX-inhibiting mode of action means it does not inhibit the production of other prostanoids, but targets the PGE2 receptor most associated with the pain and inflammation of OA26. Formulated as 20mg, 60mg and 100mg palatable tablets once daily, dosing at 2mg/kg is associated with wide safety margins and minimal side effects, the most common being vomiting or diarrhoea27.

Although a clinical study in dogs with OA found grapiprant to be an effective treatment for the alleviation of pain, this was compared to a placebo, and studies comparing it to treatments for OA will be required before it is available in the UK28. Initial safety and toxicity studies have been undertaken for its use in cats, but, as yet, no clinical studies exist on its treatment of cats with OA29. This novel treatment should prove useful in the treatment of the many dogs suffering with OA when it does go on sale in the UK.

Another class of drugs in development are monoclonal antibodies (mAb) for the treatment of chronic pain and inflammation, alongside uses in immune-oncology and allergies. Identification of mAbs against canine and feline tumour necrosis factor may result in the development of long-lasting anti-inflammatories useful in a number of diseases. Closer to reaching clinical use are the anti-nerve growth factor (anti-NGF) mAb therapies for the treatment of pain associated with OA. Initial studies in dogs have found analgesia similar to that expected from an NSAID, with effects lasting up to four weeks following single IV administration30,31. Again, these are not non-inferiority studies, so comparison to current treatments cannot be made.

Similar studies are underway for a feline anti-NGF mAb. Results show promise for the development of a well-tolerated once monthly injection for the treatment of pain associated with feline degenerative joint disease32,33. These biologic therapies are already in use in human medicine and, hopefully, will make the transition to clinical veterinary practice in future.

Expansion of specialist anaesthesia and analgesia services across the UK and the work of the Association of Veterinary Anaesthetists to provide anaesthesia CPD has raised the profile of veterinary anaesthesia in recent years. It is an evolving area of veterinary medicine with new technologies coming to the market for both first opinion and referral practices.

The prospect of some of the newer drugs that may soon launch in the UK veterinary market is exciting for the implications of provision of adequate analgesia for both acute postoperative pain and patients suffering chronic pain.