14 Jan 2019

Danielle Marturello and Karen Perry, in the final of a three-part article, look at how client compliance can impact on management of the condition in dogs.

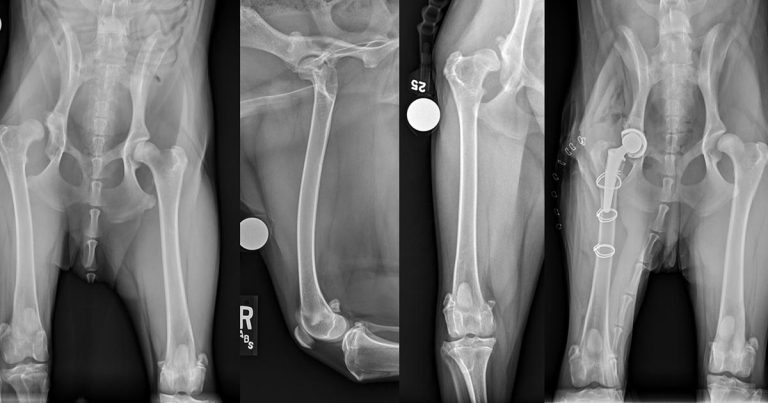

Figure 1. Pre and postoperative ventrodorsal view of the pelvis and orthogonal views of the right femur after total hip replacement for treatment of chronic luxation of the right hip. The pain associated with the osteoarthritis in this 12-month-old labradoodle did not respond satisfactorily to non-surgical management.

Canine OA is a progressively degenerative condition that affects 20% of the population older than one year of age. Management can be challenging and, at times, frustrating.

Several barriers to successful treatment exist, including a lack of appropriate monitoring, limitations to available medications, fear of adverse effects of these medications and struggles with owner compliance. This article will explore the last of these, as well as barriers encountered in the surgical management of OA. By the end of this series of articles, the authors hope to provide strategies that will help clinicians develop more successful management plans for canine patients with OA.

In the first of this three-part series investigating barriers to canine OA treatment (VT47.49), the authors addressed two challenges – the paucity of information on the epidemiology of canine OA, and the lack of attention to, and difficulty in, monitoring progress in response to various treatments.

In the second article (VT48.46), they investigated how limitations in the products available for treatment, a paucity of evidence regarding efficacy of newer treatment modalities and veterinarian or owner fears of adverse effects associated with medical management options could impact on management of this complex condition.

In this, the final part of the series, the authors look at client compliance, how it can impact on success when managing patients and how it may be improved. Some barriers that are largely encountered when considering surgical management of this challenging condition will also be addressed.

As alluded to in part two of this series of articles, as vets we are facing well-educated clients who ask intelligent questions and have high expectations. This was also highlighted in an address by Blackwell (2001). We have a responsibility to address these questions and provide client education.

When treating OA, our recommendations may include anything from prescribing medication to requesting return for follow-up appointments and advising weight loss, dietary modification or physical rehabilitation, and it is important we are ready to answer owner queries in an informed and honest fashion regarding these treatment modalities.

We have probably all experienced the difficulty that can come in advising weight loss for a given patient. Obesity in domestic pets has reached epidemic proportions, with 50% classified as overweight or obese (Bland and Hill, 2011; McGreevy et al, 2005). Obesity has been shown to be associated with numerous systemic conditions, one of which is OA. The biomechanical stresses placed on arthritic joints from excess weight are well recognised, but the obesity-associated cellular changes are just beginning to become clear.

Research has shown adipocytes secrete adipokines at higher levels in obese patients (known inflammatory mediators such as tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin [IL]-6, and IL-10), suggesting a chronic state of low-grade inflammation (Eisele et al, 2005; Trayhurn and Wood, 2004). Therefore, the correlation of obesity with joint disease is recognisable. Mounting evidence to suggest the degree of obesity will affect the body’s response to therapies meant to control pain and improve mobility also exists (Rosales et al, 2014). Additionally, these patients present a unique challenge as exercise is most helpful for weight reduction, but animals with established OA may have difficulty with activity.

As well as being prepared to discuss the evidence base behind the advised weight loss, it is important we acknowledge the difficulties in achieving weight loss in these patients and involve the owner in the plan, as his or her compliance will be critical. Encouragement at strategic time points will also likely assist in this programme, potentially through the OA clinics outlined in part one of this series of articles.

As vets, we need to be ready to have similar discussions regarding physical rehabilitation and the use of joint-specific diets. Omega-3 fatty acids are known to be beneficial for joint health. Indeed, in vitro studies have shown eicosapentaenoic acid is selectively stored in canine chondrocytes – and, therefore, will replace arachidonic acid in the inflammatory cascade (Caterson et al, 2000).

Research has also demonstrated the reduction of inflammation is an active process mediated by lipids derived from omega-3 fatty acids, illustrating again their importance for a healthy joint (Serhan, 2005). These are pieces of information that may encourage an owner to persist with a novel and potentially more expensive diet, rather than returning to the regular diet.

The discussion regarding physical rehabilitation is potentially even harder to have as evidence in small animal patients is lacking. What we do know is extrapolated from human medicine, where management of OA with modalities such as therapeutic exercise have been shown to reduce the severity of symptoms and reliance on medications (Millis and Levine, 1997).

Muscles act as shock absorbers for the body, and periarticular muscle strengthening, in particular, can help protect joints from further disrepair (Millis and Levine, 1997). Additionally, exercise can increase the production of endogenous opiates, which may help relieve OA-associated pain (Millis and Levine, 1997). Owners will almost certainly require encouragement to continue with a physical rehabilitation programme as these are often time consuming, both in terms of visits and commitments at home for owners.

In human medicine, it is estimated the range of patient non-compliance with treatment plans ranges from 30% to 60% (Roter and Hall, 1992) and most researchers agree only 50% of patients are taking their medications as prescribed (Roter and Hall, 1992). Studies involving owner compliance in veterinary medicine (Grave and Tanem, 1999; Bomzon, 1978) have investigated short-term use of antibiotics and suggested compliance is a problem. If this is the case during a short-term course of antibiotics, it seems reasonable to assume it will be an even greater problem during a life-long multimodal management programme for OA.

Factors shown to be important in improving owner compliance include spending sufficient time with the client during the consultation (Grave and Tanem, 1999), which is something we can all try to prioritise. Other suggested ways to improve compliance are establishing two-way communication and trusting relationships, a compassionate health care team, collaborative planning of the treatment regimen, and providing specific verbal and written instructions about medications with timely encouragement (Sudo and Osborne, 2000). By considering these and improving our client communication, we may be able to reduce this particular barrier to OA treatment significantly.

For cases of OA that fail medical management, surgical options exist that will alleviate the pain associated with the condition. Options include excision arthroplasty, joint replacement and arthrodesis. Several barriers exist that may prevent owners proceeding to surgery at all, and still more that may influence which option is chosen. As these are largely out of our control as vets at this stage, they will receive less attention in this article. However, although we cannot control them, an awareness of these barriers is important, as it will allow us to discuss appropriately with clients what their options may be.

Excision arthroplasty is considered a salvage procedure because normal joint range of motion cannot be restored. It does, however, provide a pain-free joint, and with appropriate and aggressive physical rehabilitation, the outcome postoperatively can be excellent. Chances of complications are minimised with these procedures because of no internal implants, but owners must be made aware of the diligent postoperative care required to achieve the best outcome.

Barriers associated with this procedure include anatomy (this procedure is only appropriate for certain joints), finances (the intrinsic cost associated with surgery and follow-up physical rehabilitation) and a limited evidence-base on postoperative outcome for some joints.

The most common excision arthroplasty is for the hip (femoral head and neck excision; FHNE) and this is really the only joint where we have some reasonable follow-up regarding how well these patients progress. The procedure can also be performed for digital and shoulder OA, but there is a paucity of peer-reviewed evidence regarding outcome following these procedures (personal communication, case reports or short passages in review articles and textbooks are all that is available). This may act as a barrier for some owners when it comes to pursuing surgery, but, unfortunately, evidence on the alternative options for these joints, excluding digit amputation, is also not plentiful.

Joint replacement is the gold standard in human medicine, but has only been available for small animals for approximately the past 40 years. Since that time, vets have continued to perfect the most common joint replacement (total hip replacement; THR; Figure 1), even creating innovative solutions for dogs with challenging anatomy that precludes placement of the standard femoral stem. To date, published results appear to be positive (Liska et al, 2009), but joint replacement is still in its early stages for joints such as the knee and elbow. Additionally, replacement of other joints, such as the shoulder (Sparrow and Fitzpatrick, 2013; Fitzpatrick et al, 2013) and ankle, remains experimental at this time.

The costs of these procedures may preclude some owners from choosing them and client communication is critical to ensure they are well informed. For example, while the cost of THR may appear substantially higher than that of FHNE initially, when all factors are considered, the situation may not be as simple.

Only a very small percentage of THR patients ever require surgery on the contralateral side, while bilateral staged surgeries for dogs undergoing FHNE is common. Therefore, when the cost of two FHNEs and associated physical rehabilitation is compared to the cost of one THR, the differential may actually swing in the other direction.

Careful patient selection is crucial for a successful outcome following total joint replacement and this will largely be carried out by a specialist surgeon. In some areas, this in itself can be a barrier to treatment. The distance to the nearest referral facility with substantial experience in total joint replacement may be sufficient to deter some owners from pursuing this option.

As aforementioned, another barrier to pursuing total joint replacement is the lack of evidence regarding long-term outcome, or even short-term outcome, in a large cohort of patients for some of these joints. Total shoulder arthroplasty, for example, has only been reported in two dogs (Sparrow and Fitzpatrick, 2013) and, therefore, remains experimental at this stage, with the long-term outcome remaining unknown. This would, understandably, make many owners reluctant to consider this modality and could also affect whether pet insurance companies would consider covering this under their plans. Until further evidence regarding these joint replacements becomes available, little can be done to surmount this obstacle.

Arthrodesis is a salvage procedure useful in cases where joint replacement or excision arthroplasty is not a good option or not possible. While arthrodesis eliminates the pain component, it also obviates range of motion, making it best suited for low-motion joints, such as the carpus and tarsus (DeCamp et al, 1993; Clarke et al, 2009; Figure 2).

Arthrodesis of more proximal joints, such as the stifle and elbow, is less successful. While still obliterating pain, the loss of range of motion of these joints results in more profound gait alterations – particularly for the elbow – and careful client communication to adjust expectations is advised prior to undertaking these.

Barriers that may prevent owners pursuing arthrodesis include some of those aforementioned, including cost, availability of a referral surgeon and the evidence base to support these surgical procedures. A final barrier, based on the experience of the authors, is largely due to anthropomorphism. Owners tend to perceive the loss of range of motion of a joint as something that will dramatically impede their pet’s quality of life. This is one barrier that can be overcome by showing owners videos of animals that have undergone arthrodesis, relaying our personal experience or reviewing the available literature – particularly for the more distal joints.

In conclusion, in this three-part series we have investigated many barriers that can complicate OA management, some of which can be either overcome or substantially reduced by clinicians and others that remain largely out of our control. Ways that we can attempt to break down these barriers and improve OA management for our patients include: