11 Dec 2017

Danielle Marturello and Karen Perry address the limited information about the epidemiology of this condition and the lack of attention to monitoring.

Canine OA is a degenerative disease affecting about 20% of dogs older than one year. No known cure exists, so treatment is directed towards palliation of the associated painful symptoms – with multimodal therapy generally accepted as the optimal treatment approach.

Several barriers complicate the management of canine OA and will be explored in this three-part series. Part one will focus on the paucity of information on the epidemiology of OA in dogs and lack of appropriate monitoring of patients being treated. The authors will discuss what clinicians can do to overcome these barriers, with the aim being to improve success rates with medical management for dogs suffering from OA.

Canine OA is a disease of synovial joints characterised by pain and lameness.

The pathological changes are thought to be predominantly attributable to mechanical factors (Henrotin et al, 2005). The first of these is abnormal strain resulting in microfractures that then remodel, causing the – often radiographically apparent – sclerosis (Figure 1).

The second is the release of matrix components that activate synovial fibroblasts and macrophages. Initially, cartilage hypertrophy predominates, but ultimately, the joint sustains a net loss of cartilage over time – leading to additional remodelling and sclerosis of the exposed subchondral bone (Aigner et al, 2001).

While in other species – such as cats – primary OA is common, an underlying cause is often identified in dogs. This affects the management of OA in dogs, as treatment of both the underlying problem and subsequent OA may be necessary to achieve optimal results.

Both congenital and acquired musculoskeletal disorders are recognised as primary factors that can lead to secondary development of canine OA. Congenital/developmental conditions include the commonly encountered hip or elbow dysplasia, and medial patellar luxation. Degenerative conditions with a genetic component, such as cranial cruciate ligament disease, are also regular causes of progressive OA.

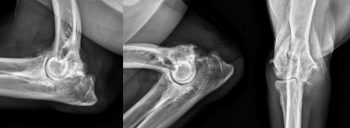

Post-traumatic OA is relatively common in dogs where it may occur secondary to ligamentous damage and resultant instability (Henrotin et al, 2005), or as a result of articular fracture (Marcellin-Little et al, 1994; Figure 2). Additionally, albeit less commonly, inflammatory (infectious or immune-mediated) and metabolic conditions can result in secondary OA.

Regardless of the inciting aetiology, about 20% of dogs older than one year are affected by OA (Johnston, 1997). No known cure exists, so treatment is directed towards palliation of the painful symptoms associated with it – with multimodal therapy generally accepted as the optimal treatment approach (McLaughlin, 2000).

A combination of analgesics, nutraceuticals, weight management, lifestyle modification, physical rehabilitation and – in some patients – surgical intervention are generally employed in the treatment of this prevalent condition. In severe cases, a lack of response to therapy can result in owners’ decision for euthanasia if they deem their pet’s quality of life to be poor, so it is critical to provide the best care possible.

Barriers that practitioners may encounter in the treatment of OA include the paucity of information on the epidemiology of canine OA; lack of attention to, and difficulty in, monitoring progress in response to various treatments; limitations in the products available for treatment; a paucity of evidence regarding efficacy of newer treatment modalities; and veterinarian or owner fears of adverse effects associated with medical management options.

When considering surgical treatment options, further barriers may include a lack of surgical expertise, limited evidence regarding the outcome following certain surgical procedures and financial restrictions for owners. These barriers will be addressed, where possible, later in the series.

In contrast to human literature, a paucity of epidemiological data is available on canine OA (Henrotin et al, 2005). However, we know it is a complex condition.

When considering treatment, a multitude of biochemical, physical and pathological alterations must be recognised. Importantly, as OA is most commonly a secondary condition in dogs, an underlying cause should be sought and either ruled out or resolved before starting treatment. Trying to control the pain associated with stifle OA in a patient with profound laxity secondary to cranial cruciate ligament disease, for example, is unlikely to be effective, whereas treatment of the same patient following stifle stabilisation is expected to be more rewarding.

The diagnosis of OA is frequently made presumptively based on physical examination findings alone, but the gold standard would include an in-depth history, physical examination and radiographic interpretation, accompanied, where appropriate, by arthrocentesis and synovial fluid analysis.

While a history typical for a patient with OA will include lameness most severe on first rising after a rest, but becoming less obvious with exercise, the history can vary, partly due to the extensive set of conditions that may precede the development of OA. Often, the pain associated with OA is chronic, which can make it challenging for owners to recognise or isolate to a single joint or limb. The history may be as vague as a gradual slowing or reduced inclination to exercise, which can lead to an extensive list of differential diagnoses – and this can be a challenge to address.

A further barrier to effective diagnosis is the typical examination findings of crepitus, soft tissue swelling, joint effusion and muscle atrophy can be similar across several disease processes (McLaughlin, 2000). Immune-mediated polyarthropathy, for example, may present with very similar findings, but necessitates a different treatment approach.

Aetiological identification is paramount to successful management, so further tests are recommended before making a presumptive diagnosis of OA. The first of these may be a sedated orthopaedic examination – an often undervalued part of patient assessment, which can be critical in assessing for instability of the affected joints.

The presence of patellar luxation, instability in cranial drawer, a positive Ortolani sign, hyperextension, or mediolateral instability of the carpus or tarsus may have a profound effect on the prognosis for the patient to respond to non-surgical management, and should be recognised and discussed with owners before starting therapy.

Arthrocentesis is another underused test in the diagnosis of OA, but is easily performed with minimal equipment required. Synovial fluid analysis should include an assessment of the gross appearance of the fluid, noting volume, viscosity, colour and transparency. Cytological evaluation should also be performed, including total and differential cell counts, and careful assessment of cell morphology. The results of this can help differentiate between a degenerative joint condition, such as OA, and immune-mediated or infectious conditions necessitating different therapies.

Radiographs are commonly, but not always, performed when diagnosing canine OA. Before making a presumptive diagnosis of OA based on a physical examination, orthogonal radiographs of both the affected joint and the contralateral joint (for comparison) are recommended to ensure the typical radiographic signs of OA are noted, including osteophytes, enthesophytes, subchondral sclerosis, effusion, soft tissue swelling and intra-articular mineralisation. This will allow other conditions with a different radiographic appearance to be ruled out, including erosive polyarthritis, osteomyelitis (Figure 3) and neoplasia, all of which would require a different therapeutic strategy.

Although less commonly encountered, the failure of clinicians to consider other potential differentials can be a barrier to effective treatment. While immune-mediated joint disease is more commonly considered as a differential, infectious conditions affecting muscles and joints (such as toxoplasmosis and Lyme disease), endocrine myopathies (such as hyperadrenocorticism and hypothyroidism) and immune-mediated myopathies are less commonly considered and ruled out, despite the fact they can all lead to similar clinical signs that may not respond to conventional treatment for OA.

What this boils down to is that, as clinicians, presumptive diagnosis of OA – based on limited diagnostics – may act as a barrier to effective treatment. All underlying causes and other potential contributing conditions should be diagnosed and, if appropriate, treated before relying on medical management to ameliorate the painful symptoms of OA. Progressing to treatment without a definitive diagnosis can certainly be anticipated to fail in many cases.

Following initiation of a management plan for OA, a crucial part of success is continued monitoring of the patient.

A treatment plan should never be cookie cutter, but tailored to the individual because the goal often varies between individuals.

The rationale for this is multifactorial. Firstly, the degree of pathology affecting both soft tissue and bone varies significantly between patients. Secondly, the severity of pain experienced by the patient does not necessarily correlate with the degree of pathological or radiographic change noted. Thirdly, the severity of symptoms is related to recent use of stress placed on the tissues, so alters between – and even within – days. Fourthly, patients suffering OA-related pain experience different types of pain – both a dull chronic ache and acute sharp, shooting pains – that likely respond to different types of analgesia.

While most veterinarians advocate monitoring for the potential adverse effects associated with many medications available for patients suffering from OA, advising regular monitoring to ensure treatment efficacy is less common. Modifications to dosages are often necessary for the best efficacy and some medications work well in certain individuals, but not others. Only with thorough monitoring can clinicians know which medications are working and which need to be altered. Regular revisits can also keep owners from becoming complacent in their pet’s care, and maintain their motivation and acuity to changes in their pet’s condition during the chronic management.

Importantly, it should be noted response to a new treatment can take up to two to three months for full effect. Therefore, careful monitoring during this time for any changes in the animal’s behaviour, activity level or general demeanour is critical in determining if the set treatment plan is efficacious

As importantly, to accurately assess which treatment modality is providing a benefit, clinicians should not start or stop multiple medications at once. Any changes should be made one at a time, with at least two months being allowed for changes in the animal’s condition to become evident, and the animal re-examined before another change is made to the treatment protocol. The authors find it is often helpful to recommend owners keep a journal for their pet, so detailed information is relayed at revisits and the management plan altered accordingly.

So, what are the barriers preventing clinicians from pursuing appropriate monitoring? While for some it may be a lack of awareness of the benefits of regular monitoring, other barriers may also play a role.

Cost for owners may be a significant impediment, in addition to difficulty in scheduling time to attend multiple appointments. A potential resolution may be to offer nurse-led clinics at a reduced cost for frequent visitors. A package price could even be considered for multiple visits, to encourage owners to attend regularly. Veterinarian-led visits could be advised if the nurse notes a negative trend in the parameters monitored.

An OA clinic could include monitoring of weight, goniometric assessment of joint range of motion, measurement of limb circumference to assess muscle mass, and lameness scoring. While these are subjective measurements and carry some attendant limitations, they will facilitate recognitions of positive or negative trends, allowing treatment plans to be adjusted accordingly.

Facilities where more objective forms of gait analysis are available – such as force platforms or pressure mats – can also be used, but these are likely to be restricted to referral facilities. Questionnaires such as the Canine Brief Pain Inventory, Liverpool Osteoarthritis in Dogs clinical metrology instrument or Helsinki Chronic Pain Index could also be distributed and collected to assess how treatment changes have affected quality of life and mobility. Other monitoring techniques, such as activity monitors (Figure 4), may also be useful and allow more remote observation.

A further barrier to monitoring appreciated by the authors, but not addressed in the veterinary literature, are the significant pressures on time as veterinarians. Seeing patients that are not progressing well is always prioritised, but this means owners are often advised the patient does not need seeing again in the absence of a perceived problem.

This can result in management problems in two respects. Firstly, owners may perceive a patient to be doing well because deteriorations are occurring so gradually they do not appreciate them, so pain management is suboptimal due to a lack of objective monitoring. Secondly, in this situation, a paucity of information exists on the treatments that work for patients with OA – information that could be used to improve treatment of other similarly affected patients.

Maybe a shift is required in our perspective, as veterinarians, that it is not a waste of time to see a patient back that has been reported to be progressing well.

In part two, the authors will address other barriers encountered in the management of canine OA, including limitations in the products available for treatment, a paucity of evidence regarding the efficacy of newer treatment modalities, and veterinarian or owner fears of adverse effects associated with medical management options.